Ema Rivas Garrido sits inside her home with her son, Humberto Ramirez Rivas, on a sunny winter day. They are nestled in the middle of a mountain village, Arroyo El Gato, in the Aysén region of Southern Chile and Northern Patagonia. The skyline is surrounded by other mountains that nearly reach the clouds. Farming animals such as cows and chickens roam through the area. While the bottom of the mountain is green with grass, Garrido’s house is situated at a high enough altitude that ankle-deep snow surrounds the village. Ramirez Rivas, who grew up in this village, has seen more snow in the past.

“This snow is nothing,” Ramirez Rivas says.

When he was a child, the snow used to be more than a metre deep.

Arroyo El Gato is filled with water, from rivers and streams that run through the area. But ten years ago, the Rivas Garrido family noticed those water channels changing.

“The water has dried up in many places,” Rivas Garrido says.

At 94 years of age, she is the oldest settler in her mountain village, having come here with her family in 1972. She anticipates the upcoming summer will be dry. Data from the University of Chile shows that the temperature in the area rose by 0.07 degrees per year from 2010 to 2016. This is similar to the global temperature rise. But with Arroyo El Gato surrounded by mountains carrying water through snow and ice, the loss of water through temperature increase is noticeable.

In Chile, the effects of climate change — warming temperatures and dryer climate — are reducing the country’s water supply.

According to the World Resources Institute (WRI), Chile is in a difficult position for water stress. Water stress is a measurement that combines temperature, precipitation, available water supply, irrigation, energy demand and population in country to determine how stressed for water a country is currently and will be for the future. Currently, Chile has medium water stress. But the increase in temperatures, decrease in precipitation, growing demand in energy and retreat of glaciers will make Chile the most water-stressed country in South America by 2040. If Chile is to avoid drastic water loss, restructuring the country needs to start now.

Managing the water supply is a significant challenge. In Chile water is treated as private property. Under the country’s water rights system, water from any location can be owned by an individual or a company. If the owner of the water right wants to trade it like a commodity, they can do so on the water market, where water rights are bought and sold as if it is on a stock market.

By commodifying water, the chances of unequal access to water rights increases. An unwelcome possibility in a country with a high level of income inequality. A 2018 report from the National Statistics Institute of Chile states that half of Chileans earn less than $550 a month, while the per capita income is around $2000 a month, meaning a large portion of Chile’s wealth is concentrated at the top of the income bracket. This inequality is further reflected by a recent government study that reported the wealthiest Chileans make 13.6 times more than the poorest.

If Chile is to avoid becoming extremely water stressed, its privatized system must make water available to everyone.

As well, the country will have to bring water to the driest areas. The north of the country is arid desert, the central region has a Mediterranean climate while the south includes mountains, glaciers and forest.

Each region has different levels of water availability and their own obstacles in ensuring residents have water access. The difficulties of accessing water will continue to challenge Rivas Garrido and Ramirez Rivas, as well as the rest of the country.

Near Victoria Marincovic’s suburban neighbourhood of El Arrayan is a bridge over what is technically classified as a river. That river is now reduced to a stream, with bushes and soil taking up the space where water once flowed. Once upon a time there were trees behind Marincovic’s house, but now the soil is so dry it can no longer sustain them.

“I didn’t have a view from here before – I just had pines,” Marincovic said of the trees that used to block her from seeing the dry mountain behind her house.

“They were huge. And they’re not there anymore.”

Marincovic lives in the Metropolitan Region (MR) of Chile, which is the central area of the country where 70 per cent of the population lives. With the Andes mountains on one side and the Pacific Ocean on the other, its geography features valleys, rivers, and water basins.

Despite a mediterranean climate, this region has a big problem: it is losing water rapidly.

According to the Chilean Antarctic Institute, the MR has lost three centimetres of precipitation each decade since the 1970s. Over that period, Chile lost between 8-15 gigatons of water, which is the amount of water New York City uses in a year eight to 15 times over. Since 2010, the area has been in the grip of what has been termed “the megadrought” — the largest recorded drought in Chile’s history. As a result, 37 per cent of the region’s water supply has been lost.

Marincovic says she and others in her neighbourhood know this drought is an example of climate change reducing their water availability. But she and other residents of El Arrayan insist that climate change is not the only problem.

“Look, a year ago we started to become aware of what was going on,” Marincovic says.

She is referring to the Los Bronces mining project near El Arrayan. The project is majority owned by the British based mining company Anglo American. The Los Bronces project is Anglo American’s flagship mine in Chile and is estimated to hold 30 per cent of Chile’s copper.

The mining project also requires a significant amount of water. To extract copper the process involves pumping a mixture of copper ore and liquid, called a slurry, through a pipeline. The Los Bronces mine pumps a copper slurry through their pipelines at a pace of 700-800 litres per second. But approximately 500 litres of that is actually water. For the overall operation, Anglo American stated in their shareholders meeting it uses close to 710 litres of freshwater per second.

Most of that is freshwater from local reservoirs for which Anglo American has obtained the water rights.

Marincovic says as a result of the Los Bronces mine, residents in El Arrayan have to dig their wells to 150 metres below ground to access water.

“It used to be 50 (metres), then 100, and we had to dig the wells deeper and deeper,” Marincovic says.

In El Arrayan, a group of increasingly concerned neighbours began messaging each other, warning of ecological damage. The messaging culminated in a community WhatsApp group called ‘Let’s Save El Arrayan’ of which Marincovic is an active member.

“We have created this organization because we want to raise awareness and help to mitigate climate change,” Marincovic says of the WhatsApp group.

The company responded by saying it will take a multi-pronged approach to ensure critical areas for water are not disturbed and that long-term water security of residents is guaranteed.

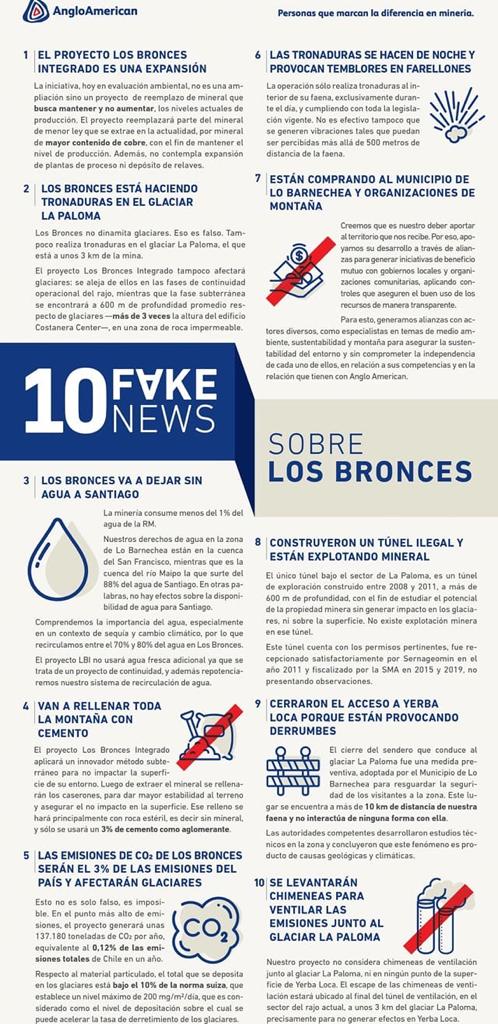

However, the Chilean news outlet Interferencia published an investigation showing the Anglo American project would emit more than three per cent of all CO2 emissions in Chile and permanently damage nearby glaciers. In response, an Anglo American public relations employee in El Arrayan sent a poster by Anglo American to community members that claims the Interferencia story is fake.

Anglo American has also been accused of illegally transferring funds to government bodies involved with the environmental assessment of the Los Bronces project. According to an investigation by the Chilean publication CIPER, more than $300 million from Anglo American was transferred to the Municipality of Lo Bernechea. Under the Comptroller’s Office this type of contribution is illegal because the Lo Bernechea municipal government is the community authority that is supposed to participate in the Los Bronces environmental assessment.

Anglo American’s assertions of environmental responsibility ring hollow to Marincovic.

“It doesn’t mean that if we oppose the plans the mine will stop working,” Marincovic says. She does not believe Anglo American is making enough efforts to conserve water or avoid environmental damage to the surrounding area.

“For us, the laws should be transformed, and the government should support the citizens so that we can use the water for our own consumption — for us and all living beings here — the plants and animals.”

On the left side, the growing gray circle is what has become the Los Bronces mine. On the right side, is a gradually melting glacier. Map Data: Google

Despite the growing water shortage, urban areas in Santiago have access to clean drinking water. That might change. Santiago gets its water supply from the Maipo River Basin. The Maipo River river flows from the Andes to the Pacific Ocean, the basin is 50 km south of the city. By 2070, 40 per cent of the water supply in the basin is expected to be depleted because of decreased precipitation and glacial retreat.

Residents of rural areas around the Metropolitan Region are already feeling the loss of water access.

Areas that were not previously without water are going dry. In the small town of Petorca, people struggle for drinking water while avocado farms in the region have plenty of water and water rights to continue production. Lake Aculeo was once a tourist destination. Now it is dry. Last year, more than 50 rural communities needed water trucked out to them by the federal government.

The water rights allocated for each level of the Maipo River Basin matter when looking at water scarcity, according Andrea Becerra, a consultant and water code analyst to the non-government organization Natural Resource Defence Council (NRDC). Santiago draws its water from the Yeso Reservoir, which is a reserve of glacial water in the Maipo River Basin. Since the Yeso Resevoir is fed by the glacier it is slower to lose water than other parts of the basin. The fact that Santiago gets access to clean drinking water masks the reality that the rest of the Metropolitan Region is desperate for water, Becerra says.

Adding to that problem for the Metropalitan Region is that there are more water rights in rural areas than actual water. According to Becerra, if the current model for water distribution does not change, water will become too scarce and expensive to access.

“It’s a very apocalyptic view into the future but it is a reality,” Becerra says.

Map of Chile with Landmarks

Instructions for Map

- Start by scrolling closer into Chile on the map

- Use the ‘+’ and ‘-‘ on the bottom left of the map to scroll deeper into the map or further out. You can also scroll with your mouse. They are the exact same features as a Google Map

- The blue pins on the map indicate landmarks of Chile that are mentioned in this story

- Clicking on the blue pins will give the title of the landmark and its description

The Water Code was implemented in 1981 by the regime of Augusto Pinochet, a dictator who ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990. Under his regime, Chile became heavily privatized, with government playing less of a role in regulating and participating in the economy. The Chilean Constitution of 1980, which is still in effect, helped reinforce privatization by selling off nationalized resources. The Water Code served as an extension to the constitution and helped water become one of those privatized resources, as stated in Article 24 of the 1981 document: “the rights of individuals over water, recognized or constituted in accordance with the law, grant their holders their ownership.”

When Chile democratized again in 1990, the infrastructure for privatized water was retained. In 2011, the Chilean government sold its stake in three major water companies for just over $1.5 billion.

The Chilean federal government acknowledges the effects climate change on its water supply. When speaking in a press conference about the country’s previous abundance of water, current Chilean President Sebastian Pinera said, “Climate change and global warming have changed that situation perhaps forever . . . We have to get used to using resources such as water and energy more effectively.”

To tackle climate change, Pinera’s government has pledged to be carbon-neutral by 2050 and for two-thirds of the country’s energy to be renewable by 2030. The government have also said they are a working on a new government framework for addressing climate change.

Alex Godoy Faundez disagrees with the government’s direction on water rights. As Director of the Center for Research on Sustainability and Strategic Resource Management at the University of Desarollo and co-author of multiple research papers on water resources and laws, he is an expert on the water code.

“The problem is the mechanisms for water rights today are not able to solve the physical problems,” Faundez says.

By putting a price on water, Faundez says the water rights system allows wealthier Chileans and industry to buy the most valuable water in the mountains and reservoirs. Meanwhile everyone else in Chile gets whatever water is left, whether it is clean or not.

Chile’s distribution of drinking water is complicated. There are more than 40 water-related institutions doing more than 100 different functions according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), an economic organization that consists of some of the world’s most economically influential countries. But most of the government decisions on managing and distributing water through companies is centralized at the national level. The most involved of these government bodies is the General Directorate of Water (DGA). The DGA is responsible for water resource planning, most notably. This includes issuing and regulating water rights to companies who disseminate the water to Chileans.

Responsibility for how private companies disseminate drinking water in urban areas is done though the government department called the Superintendence of Sanitation Services (SISS).

Individuals purchase their water through one of the few water companies that departments like the SISS grant water rights. The problem in this system is that government have sold large portions of water distributions to only a few water utility companies, which can monopolize water services in their areas. One example is the Ontario Teachers Pension Plan, a private pension fund in Canada, that owns most of the water services in cities such as Valparaiso and Coquimbo and in regions such as Maule and Bio Bio.

Between 1999 to 2001, when a large swath of water resources were privatized, rates on drinking water spiked as high as 400 per cent and Chileans consumed a third less water to compensate for the costs, according to the non-government organization Organisation of Consumers and Users of Chile (ODECU).

Service quality is eroding as well. According to the SISS, Chileans have become increasingly dissatisfied with their water distribution since 2008. Dissatisfaction reached a low in 2015 when only 10 per cent of Chileans approved of their water services.

Chile is not the only country where water is privatized. Others include England and Australia. The difference, Faundez says, is that other states have more power over privatized water within their own borders. In Australia, water can be expropriated, while in Chile water is seen as private property.

“In Chile, you cannot modify a property right.” Faundez says. “We have one solution, and the solution is to reform the constitution. And this solution is not easy.”

Cristina Dorador sits on a panel with several experts for a discussion on how to deal with water issues in her northern Chilean city of Antofagasta. Even though it is situated directly beside the Pacific Ocean Antofagasta is an arid city. It sits in the Atacama Desert, the driest area in the world.

As a microbiologist who studies the ecology of northern Chile at the University of Antofagasta, Dorador is knowledgeable about the challenges of water use in this region. She also has another advantage for understanding this place: she grew up here.

Dorador grew up in Mejillones, a port city 60 kilometres from Antofagasta. She says in her childhood, northern Chile had more balanced weather, as it would rain just enough and the temperature stayed consistent.

“It used to be heaven,” Dorador said.

When Dorador was a child northern Chile was already experiencing water scarcity. The Loa River drying up and changing patterns of condensation are making the scarcity worse.

These climate change problems are exacerbated by mining practices that deplete what is left of water resources and have led to increased desalination.

Antofagasta has a history of mining dating to the nineteenth century. Currently mining represents 65 per cent of the region’s GDP. In a country where mining takes up three per cent of total water usage, it accounts for almost half of Antofagasta’s water use according to the OECD. The increase in demand for lithium, which is the key component in lithium ion batteries, has expanded mining activity and its water use.

The Salar de Atacama salt flats, which neighbours Antofagasta, hold nearly half the world’s lithium. The demand for that lithium is expected to triple by 2025, as lithium-ion batteries are necessary to power electric vehicles and renewable energy sources.

From 1997 to 2017 the area of Salar de Atacama mined for lithium has quadrupled to 80 square km.

The process for mining lithium is different from harder minerals like copper. Lithium is extracted by pushing the ground water beneath the brine of the salt flat to the surface. An investigation in Engineering and Technology estimates that more than 433 billion litres of water have been lost in northern Chile from 1985 to 2017 because of lithium exploration. That same investigation estimates that 1.4 trillion litres of water will be lost between 2018 and 2043 with the current levels of lithium extraction.

“It’s so massive,” Dorador said of the scale of the mining.

According to her, residents near the lithium mines believe this type of extraction is responsible for the water loss occurring in their area.

What Dorador says is necessary for northern Chile is a more balanced approach to mining and water resources.

“This idea to always grow the economy (through mining) will kill the ecosystem,” Dorador said.

A widely seen solution for water supply problems from mining in northern Chile is desalination, which is the process of taking salt water from the ocean and removing that salt to make the water drinkable. Chile got its first desalination plant in 2003 for the purpose of providing potable water to its residents. That plant is now the largest in Latin America and provides 80 per cent of potable water in Antofagasta. By 2029, desalination plants are expected to triple their seawater use and the amount of plants will double. The demand comes from mining companies. In Escondida, site of the world’s largest copper mine, the mining company BHP spent more than $3 billion on a desalination plant.

Desalination can be a positive, as it provides drinking water for an arid city in Antofagasta.

The difficulty is the amount of energy required for desalination. According to COCHILCO, Chile’s mining commission, desalination’s energy output is expected to increase by 40 per cent by 2030, from 23.6 terawatts to 33.1 terawatts. This is enough energy to power the world for almost two hours.

“You see the contradiction,” Dorador said. “You’re using carbon to desalinate and use carbon for lithium mining companies that are supposed to decarbonize the world.”

Southern Chile does not have the same water problems as the rest of the country, especially in the Aysén region. Yet as Rivas Garrido and Ramirez Rivas said, they have noticed water loss in their community. That water is essential not only for life, but for the work of the community in Arroyo El Gato, Rivas Garrido says. Most of the people living in this mountain village farm cows, goats and chickens. All of these animals need grass to roam and water to drink.

Rivas Garrido has been farming here with her family since 1972 when they moved into a small cabin a football field away from where she lives now. In that small cabin she and her husband raised 10 children. According to her, the winters were much longer then.

“In April it was already snowing,” Rivas Garrido said, referring to what is mid-autumn in Chile.

Aysén’s challenge with water loss is an example of what is happening throughout southern Chile. Even though Aysén is losing water the general population does not recognize this reality. Those who do realize their is water loss in Aysén cannot collect enough data to properly track the decrease.

A recent study by researchers at the University of Chile study found that snow cover in Aysén, the region Arroyo El Gato is situated in, has decreased around 20 square kilometres a year between 2010 to 2016. During that same time frame, the study found that precipitation and water flow in streams in the Aysén region had decreased at rate of more than 8 millimetres a year.

Around 80 kilometres from Arroyo El Gato is Coyhaique, the capital city of the Aysén region. Settled in 1929, the snow-covered mountain tops surrounding Coyhaique give it the nickname ‘City of Eternal Snow’. In an office in the city, Pablo Rivas makes mate, an Argentinean drink similar to tea. Rivas is the manager of the Economic and Development Unit at City Council and works extensively with people in rural villages like Rivas Garrido. According to Rivas, most people living outside farming communities in the Aysén region are not concerned about the decrease in water because it is still available to them. But Rivas says this availability will not continue.

“Now in the summer you have 35, 37 C and its melting all the glaciers. That’s a problem.”

That trend was reflected in 2011 when Chile’s Center for Scientific Studies released a report that stated 90 of the 100 glaciers they monitored are retreating. Gino Casassa, the DGA’s Chief of Snow and Glacier division, attributes the loss of glaciers to climate change. He co-wrote an article in the journal Frontiers in Earth Science stating that a peninsula along Southern Patagonia lost 19 per cent of its snow cover between 1972 and 2016. Casassa attributes this loss of snow cover to the temperature of the area warming by 0.71 C.

While that data provides clarity for glacial melt, there is still more research needed according to Brian Reid and Anna Astorga.

Reid comes from the United States while Astorga, who is half-Chilean, came to Coyhaique from Finland. Both are researchers with the Center of Investigation for Ecosystems in Patagonia (CIEP), located just outside the city. Their challenge is finding out how to quantify the loss of water in Southern Chile.

“We know they’re (the glaciers) retreating, but the information on discharge and flows is almost non-existent in Chile,” said Reid.

According to Reid and Astorga, this means more difficulty in tracking how much water is in critical watersheds, lakes and rivers in the region. Without knowledge of water being lost from a supply, it is too difficult to predict how much is left and at what pace it is diminishing.

Reid says measuring how much water flows through a river in the past does not help predict the future. The decline in water now is more rapid than it was in the past.

Making matters more difficult, Reid says there is not adequate staffing or resources to track water loss in sourthern Chile.

According to him, less than one per cent of the people in Chile that research water are in southern region of the country, where most of the water is located.

But Astorga is hopeful for southern Chile’s water supply. There is still 60,000 km of water at the top of the mountains in southern Chile and she says there is time to craft policies that will help retain the region’s remaining water.

Within government, Felipe Henriquez, a representative of the Ministry of Agriculture in Aysén , is involved in planning how water is allocated.

“We have to focus on that, because we have already seen not only in Chile, but in other parts of the world, that the issue of drought is an issue that has to alarm us.”

Where Henriquez differs from other experts who are studying water loss is that he defends the water rights system. According to him, water scarcity can be solved through the private sector. Henriquez also argues that climate change has positives. To him, it presents an opportunity for economic growth. He says that rising global temperatures will change southern Chile so more agricultural projects like cherry farming will be possible.

“We are seeing climate change in Aysén as a threat, but we are also looking at it as an opportunity,” Henriquez said.

Reid has a different perspective.

“Even though this is an area of water abundance it can’t stay that way forever,” Reid said. “There’s going to be a big crash.”

A large number of Chileans have recently shown they will not tolerate further privatization of their country. In mid-October a 30 peso increase in bus fare, which is five cents Canadian, sparked mass protests throughout Chile. Income inequality and a poor standard of living have been the main reasons Chileans were protesting before the COVID-19 pandemic. Chile is the third most economically unequal country in the OECD, behind Costa Rica in second and South Africa is first, but ahead of Mexico in fourth.

After the protests grew, President Pinera responded by calling a state of emergency on Oct. 19, 2019. On Nov. 15, after a month of protest, the Chilean Congress signaled the country would have a plebiscite in April 2020 to answer the question of whether Chileans want a new constitution. If the result of the plebiscite is to make a new constitution, there will be an opportunity to rewrite the water laws for the country. But with COVID-19 putting the country lockdown from mid-March to August that plebiscite has been pushed to Oct. 25.

More footage of the #ENEL building, a symbol for Santiago, engulfed in flames. According to news sources, protesters are setting fire at toll gates at highways around the city as well. The whole #EvasionMasiva is turning in complete outrage. pic.twitter.com/RFOmVjSTIw

— Boris van der Spek (@BorisvanderSpek) October 19, 2019

Water is one of the issues that ties into income inequality in Chile according to Javier Cifuentes, who is one of the many Chileans protesting for a new constitution.

“We have a system that gives privilege to a small group of rich people,” Cifuentes said.

The protests have led to widespread damage of buildings, thousands of arrests and 31 deaths. The most noticeable building burned down is the Enel Building, which is named after one of the largest power companies in Chile and one that holds a significant amount of water because of hydroelectric projects.

To commemorate the anniversary of the first protests, Chileans protested by the thousands in Santiago on Oct. 18, 2020. Two churches were burned down in the process, including San Francisco de Borja, a popular church among the Chile’s national police force.

Boris Van der Spek has been covering these protests as a journalist and founder of the publication Chile Today. While COVID-19 may have stalled progress on voting, he believes a constitution will be written.

“But it’s such a long way to go,” Van der Spek said.

A constitution is a massive document, Van der Spek mentions, and it takes time to craft it.

Chileans will get a new constitution if polling is accurate. Recent polls have nearly 70 per cent of Chileans wanting a new one.

Even though Pinochet was kicked out of power two years after the 1988 plebscite, the constitution his regime implemented in 1980 has remained, ensuring the dictator’s influence over the country.

In a less direct way, climate change is also a reminder of the policies engrained under Pinochet. As each area of the country continues to dry, Chilean’s must grapple with how to manage a critical resource in water. The Water Code implemented during the dictatorship has resulted in water being more accessible to those that can afford it.

“There are a lot of places in Chile that don’t have access to water and now it’s a problem,” Cifuentes said, who himself did a research project on water loss in central Chile when he was a student.

A new constitution brings the promise of change, but a more equitable water system is not guaranteed. The current President of Chile, Sebastian Pinera, has a disapproval rate of nearly 80 per cent according to the polling firm Activa Research. Over 60 per cent of the Chileans polled also do not believe Pinera’s efforts to alleviate social inequality during the pandemic was good enough. With national elections not happening until next year, Pinera and his party, National Renewal will have an impact on shaping how the Water Code changes.

While the situation is not perfect, Dorador says a new constitution is needed. She has been studying the connection between climate change and water loss for a good portion of her academic career. Dorador is aware of how climate change is ravaging her country and how the current water laws mean that Chileans will struggle to access drinking water now and in the future.

A new constitution will not prevent climate change, but Dorador says it has the potential for Chile to manage such a precious resource more fairly.

“Water has to belong to everyone.”