Helping or hurting? Whale watching in the St. Lawrence

Just before 10 a.m., people line up in front of a small building tucked behind the whale interpretation centre to get bright orange jackets and black overalls. They chatter as they walk back across the road, down a rickety metal ramp to a large zodiac boat tied at the dock.

This morning, the sun is shining on Tadoussac, Quebec and the parking lots are already full of cars, the boardwalks scattered with tourists strolling, talking and occasionally looking out over the water, hoping to catch glimpses of the minke whales that come into the bay.

This morning, the sun is shining on Tadoussac, Quebec and the parking lots are already full of cars, the boardwalks scattered with tourists strolling, talking and occasionally looking out over the water, hoping to catch glimpses of the minke whales that come into the bay.

Around 50 people are herded onto the zodiac, the ropes are untied and the boat takes off, an announcer giving safety directions over a load speaker in both English and French.

Education about whales takes place off the boats as well as on. In and around the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park, there are many visitor reception, interpretation and observation areas. Some are operated by Parks Canada and some are not. Tourists can watch whales from land, while learning about whales’ lives and issues of conservation through displays, plaques, videos and staff members.

Pierre Beland, head scientist at the St. Lawrence National Institute of Ecotoxicology said, “If you are familiar with whales and you develop a relationship with them, then it’s more likely that you will want to preserve them. This is the only positive aspect of whale watching tours.”

While money from tourism helps fund the park and maintain a robust economy in the area, the practice of whale watching isn’t without consequences. Aside from ensuring a protected area with strict regulations, going out on boats to view whales doesn’t do the whales much good at all.

“It’s a privilege to be able to observe marine mammals in their natural environment, but with that privilege comes responsibility,” said Valentyna Galadza-Park, external relations manager for the marine park. “I think that’s really important, that we take quite seriously our impact on their environment, and remember that it’s us visiting their environment and they’re not there just to amuse us.”

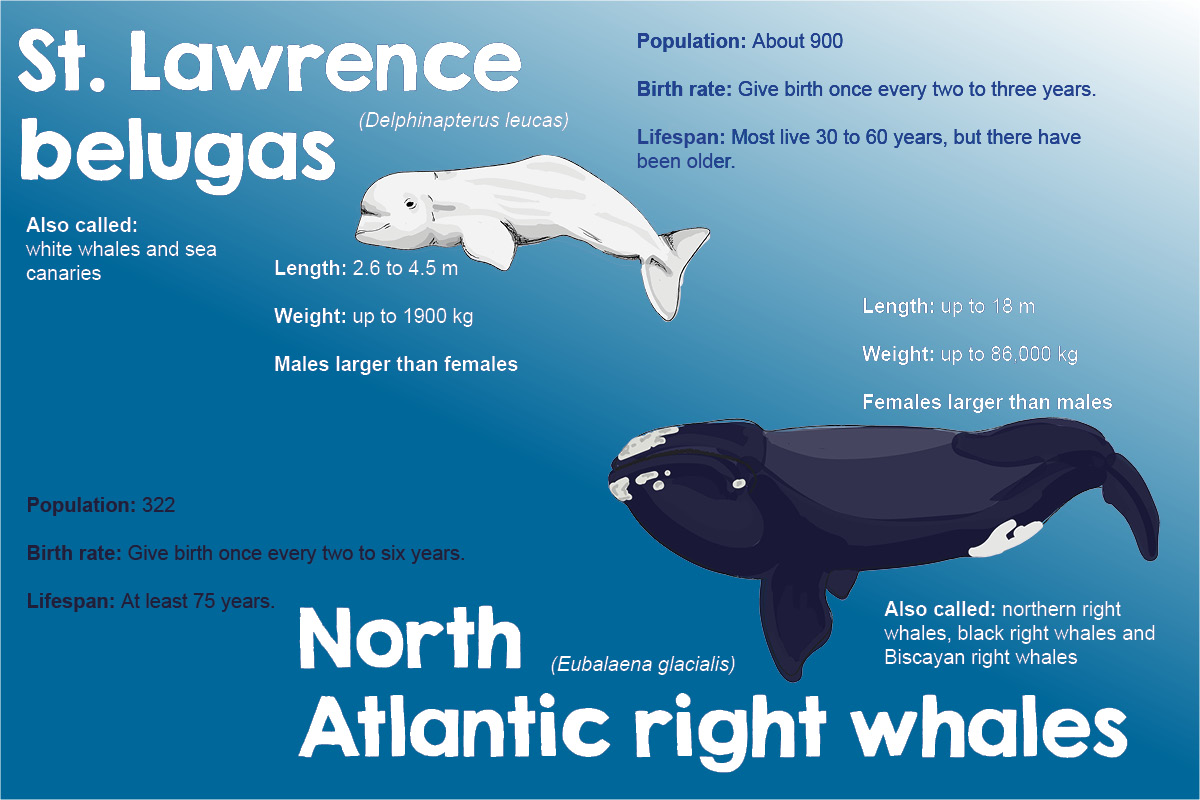

Belugas and right whales

The federal government put up a website this summer called, “Let’s Talk Whales,” calling for Canadians to give advice on how best to deal with the current declines in whale numbers. The three whales it gives priority concern to are the North Atlantic right whale, St. Lawrence belugas and the Southern Resident killer whale, which lives off the Pacific Coast.

The website identifies food availability, underwater noise, entanglements, contaminants and vessels as the five main threats these whales face.

The website identifies food availability, underwater noise, entanglements, contaminants and vessels as the five main threats these whales face.

In James Higham’s book, Whale-watching: Sustainable Tourism and Ecological Management, the New Zealand professor of tourism and ecology concluded that whale watching doesn’t often directly kill whales, but it can make profound and damaging changes to their lives.

Jon Lien, a former whale rescuer and professor at Memorial University, had similar concerns in his 2001 report on the effects of whale watching in Newfoundland. He pointed to the many ways whale watching boats interrupt life for whales, making it harder for them to feed, breed, travel and communicate and called for more protection for the animals.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada is using Lien’s report in its consultations on how to change Marine Protection laws in Canada to better protect whales. The ministry was supposed to make changes directly addressing whale watching sometime between 2015 and 2017, after beginning public consultations in 2003. Thus far, it’s still in its consultation phase.

While Lien implicated whale watching as being at least indirectly related to these threats as they affect fish populations, cause noise and can leach contaminants into the water, tourism is largely left out of the government’s new website, except for a brief mention in the report on belugas.

In his argument for whale-watching-specific marine mammal regulations, Lien wrote that endangered, threatened and vulnerable species were particularly in danger of being affected because whale watchers tend to go to areas of critical habitat and because whale watching is competitive and vessel operators seek to make the experience more attractive by getting close to the animals or by pursuing them, whale watching alone, or because of cumulative effects, may entail conservation risks.”

As the two most threatened whale species in the St. Lawrence estuary and gulf, right whales and belugas are the animals with the most to lose from any threat to their habitat, including whale watching.

Threats to whales in the St. Lawrence

Ships

Ships

Some of the biggest threats to both belugas and right whales are the large ships in the St. Lawrence Estuary and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Nearly 8,000 commercial ships travel the river each year, with about 4,000 traveling from May to October when there are the most whales present.

The ships cause collisions with whales; make large amounts of noise, disrupting whale communication; and introduce pollutants and foreign species that cause disease and disrupt ecosystems.

The ships cause collisions with whales; make large amounts of noise, disrupting whale communication; and introduce pollutants and foreign species that cause disease and disrupt ecosystems.

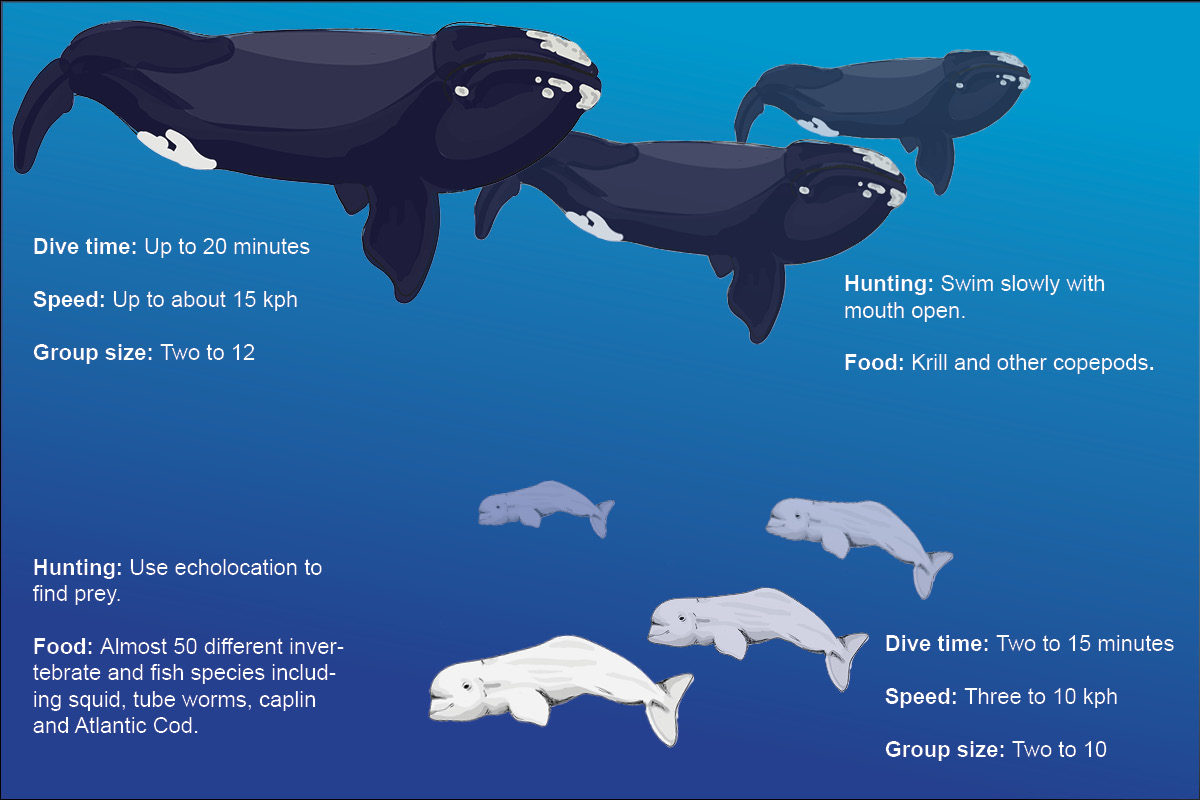

Belugas use a form of communication called echolocation. They send out sound waves that bounce off objects and return, telling them about their surroundings.

Modern ships create up to 200 dB of noise from their propellers, engines and bearings, disrupting beluga echolocation and effectively, blinding them. Tour boats typically output about 140 dB of sound, about equivalent to a rock concert. Studies have found that human-caused underwater noise interferes with beluga feeding, mating and nursing up to 10 km away. The whales will avoid the sources of noise up to 40 km away. In the narrow St. Lawrence, that doesn’t give them much room to work with.

The disruptions are especially hard on baby belugas, who can lose contact with their mothers and pods, and some end up dying. Some belugas have been known to get disoriented and beach themselves.

Scientists, in performing whale autopsies, have found evidence of hearing loss caused by noise. They suspect this deafness makes the whales more vulnerable to being hit by ships, losing out on mating opportunities when they can’t find mates or being unable to hunt.

Even when the noise doesn’t cause deafness or fully interfere with echolocation, the effects of constant and repeated noise change their behaviour. In the late ‘90s, researchers found that belugas in the Saguenay River area, in Quebec, communicated less frequently when there were a lot of boats nearby.

While right whales are not known to use echolocation for communication, researchers Scott Kraus and Rosalind Rolland suggest that ambient noise in general may inhibit the whales’ ability to hear mating calls over long distances, giving them fewer chances to reproduce.

After 9/11, when there was almost no boat traffic on the Eastern Seaboard, Rolland tested right whale poop and found significantly lower stress hormone levels than at any other time. Because there isn’t much information on what right whale lives were like before contact with large modern ships, it’s hard to know exactly how their lives have changed in the past century, but continuously dwindling numbers with few clear answers suggest the ship traffic may be a part of it.

Further, 12 North Atlantic right whale died in the Gulf of St. Lawrence this year, with another four found dead in Cape Cod, effectively taking out more than three per cent of the total population. After an autopsy, researchers found at least one of the deaths to be from blunt force—a ship likely being the only object big enough to hit the whale hard enough to kill it.

Many ships are so large and loud that any person on the ship won’t notice a collision when it happens. If someone does notice a whale, the ships are usually going too quickly to avert hitting it.

Several years ago a group including the Coast Guard, the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park and others, did a study finding that lowering boat speed in the St. Lawrence could reduce whale deaths. The researchers worked with the Coast Guard to ask pilots to voluntarily slow down their ships. In 2013, 13 per cent of ships were traveling below about 12 knots. The next year, after being asked to slow down to help whales, 72 per cent had reduced their speed and the number of whale deaths decreased by 35 to 40 per cent.

This year, Fisheries and Oceans Canada Minister Dominic Leblanc told Global News in August he had concerns that the United States could restrict Canadian goods under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, if he department didn’t take action to lower boat speeds. Fisheries and Oceans Canada formalized the speed limit to 10 knots on Aug. 11.

Fishing gear

Some estimates have as many as 10,000 whales dying from being trapped in fishing nets each year. Many whales are harmed by fishing nets, buoy lines and lobster traps. North Atlantic right whales come into contact with them so often, that scientists use the scars from these encounters to identify the individual whales. The nets can give whales deep cuts; damage teeth, muscles and jaws; and sometimes amputate fins or tail flukes.

Gill nets are some of the biggest threat. These are sheets of netting suspended in the water. They’ve been a serious problem for whales since the 1950s, when fishermen started using nets made of synthetic fibres. Large whales could break the natural nets, freeing themselves, but the stronger monofilament nets could get permanently caught on the whale.

Gill nets are some of the biggest threat. These are sheets of netting suspended in the water. They’ve been a serious problem for whales since the 1950s, when fishermen started using nets made of synthetic fibres. Large whales could break the natural nets, freeing themselves, but the stronger monofilament nets could get permanently caught on the whale.

A scientific trial in the waters off the southwest of England found that a new technology called pingers could help reduce whales getting caught in gill nets. The pingers emit pulsing sounds that alert whales to the nets. However, the sound can attract seals and sea lions looking for fish, entrapping them. Further, the technology is expensive.

People will sometimes work to free whales from the nets. Scientists in New England credit the work to free whales with helping humpback whale populations to rebound. However, while humpbacks will relax and allow themselves to be freed, right whales tend to panic and try to bolt and thrash.

Joe Howlett, a New Brunswick fisherman who founded a whale rescue organization, died while freeing a right whale from his nets in July of this year. This led the Canadian and American governments to ban attempting to free right whales from fishing gear.

Pollution

Beluga bodies in the St. Lawrence are considered hazardous waste and must be removed from the water. Through necropsies, University of Montreal researchers have found the whales carry many tumours, some cancerous, in nearly all of their body systems; viruses; infections; and numerous toxic chemicals, metals and poisons, including PCBs, DDT, chlordane and toxaphene. Scientists have also found that female belugas stop reproducing after age 21, while their northern cousins in the Arctic continue breeding their entire lives.

Some of the chemicals correlate with aluminum smelters on the Saguenay River—higher rates of cancer have been found among nearby human populations as well—although the representatives at the smelters have denied responsibility.

Some of the chemicals correlate with aluminum smelters on the Saguenay River—higher rates of cancer have been found among nearby human populations as well—although the representatives at the smelters have denied responsibility.

Further, both Montreal and the city of Quebec have dumped millions of litres of raw sewage into the St. Lawrence.

Joe Roman and Jim McCarthy performed a whale poop study, finding that the feces helps bring nitrogen to the surface of the water and helping other life to thrive. Human sewage tends to sit at the same water level as whale poop. With a significantly different diet from whales, human feces can potentially interrupt whale scat’s function in the water.

In “The Urban Whale,” researchers Kraus and Rolland write about a study in 1994 that suggested right whales have low enough levels of similar toxic substances to not negatively effect them. However, they also cite a 1996 study that suggests those levels may be affecting reproductive rates because calves are exposed to higher levels through their mothers’ milk during their early development.

Whale Watching

At one time whales were widely seen as vicious predators. Captive whales and films and TV shows like the work done by Jacques Cousteau have helped change public perception. Marine parks with captive animals have come under criticism for being unable to adequately care for large mammals, so many tourists looking to have a whale encounter have turned to whale watching.

The industry creates jobs in areas depressed by decreasing fish stocks and hit by the whaling ban. It also encourages people to support whale conservation initiatives. Japan, Norway and Iceland, countries that continue to hunt whales in spite of the worldwide ban, manage to have both whaling and whale-watching industries simultaneously.

The industry creates jobs in areas depressed by decreasing fish stocks and hit by the whaling ban. It also encourages people to support whale conservation initiatives. Japan, Norway and Iceland, countries that continue to hunt whales in spite of the worldwide ban, manage to have both whaling and whale-watching industries simultaneously.

Some of the downsides of whale watching include the fuel burned by planes, buses, cars and boats to get tourists to the best locations. The biggest concern is that boat operators are competitive and the drive to give tourist the best views can take precedence over the needs of the animals. The tourism boat traffic can be disruptive to whale feeding, mating, nursing and resting.

Operations that encourage swimming with whales are considered extremely damaging to the creatures as it can be stressful and unhealthy, especially if it involves feeding them.

Between 1990 and 1999, whale watching tourism grew at 12 per cent volume per year—and that was before everyone had a smart phone and access to tourism information at their fingertips.

Researchers Rolland and Kraus point to the heavy regulation of right whale watching in the U.S. as reason that it is one of the least concerning activities affecting the whales, when compared with ships and fishing gear. They also suggest, as many have, that whale watching could win the right whales allies by teaching tourists about their plight.

This is similar to the work done in the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park with belugas. Within the park, which covers much of the belugas’ summer range, whale boat operators are not allowed to approach the white whales at all and may not stop, even from a distance. Tourists who wish to see belugas must watch the whales from land.

Whale watching on the St. Lawrence

People and whales

For hundreds of years, when people interacted with whales on the St. Lawrence it was only to hunt them. The death of a whale meant food, oil and building materials.

For whalers, the animals could mean even more than those things. Foremost, whales were commodities the men could trade for nearly anything they, their families and their communities might need. Whaling was a way to provide.

More than that, whaling was a way of life. The Basques traveled from the Bay of Biscay, across to Newfoundland and Labrador, and down into Quebec, as far south as Trois-Pistoles. They spent months each year in temporary communities along the shores of the St. Lawrence, catching whales and turning them into the products they could trade locally with the Innu First Nations and the rest they could bring back and trade in Europe.

The transition from hunting to watching is less than a century old and coincides with plummeting whale populations. Click through the timeline to see how the relationship has changed over time.

Tourism in the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park

Blue signs along the road announce to tourists that they are driving along the whale route. Arrows point them to observation points in nearly every small town along the St. Lawrence, some official with plaques and seating, as well as docks and interpretation centres. Some are just collections of tourists sitting and watching from shore, looking to where the whale-watching boats are gathered and tell-tale spouts of whale breath on the surface.

Nearly 10 years ago, the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park was formed in this area to help protect belugas from the threats to their existence and provide a space for scientists to research them more in-depth. It also provides extra regulation to the tourism industry than was growing on the north shore of the estuary.

“The angle that we take is to promote awareness of human impact that we have, that humans have on marine mammals, and the importance of respecting the regulation that exists in the park to reduce our impact on their habitats,” said Galadza-Park, external relations manager for the park.

Whale watching is an part of the tourism industry, controlled by the park, but as Galadza-Park pointed out, not run by it.

However, the park does benefit from whale watching, as it draw visitors from around the world to its shores and out onto its boats. Visitors bring in money that helps the park continue to exist and helps to fuel the economies of the seven bordering communities.

Further, it helps people to feel invested in the future of whales. Galadza-Park said, “It’s like anything, the more you know about it, the more you’re going to appreciate it, and hopefully love it, and hopefully want to protect it.”

Help versus harm: What’s in it for the whales?

The Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park provides some of the strictest marine mammal regulations in the country, providing a haven for the whales and other creatures that live there. The funds coming in from tourists each year—about $205 million in 2005—help maintain the park and provide jobs within it, as well as to the surrounding communities. The park gives researchers an opportunity to interact closely with whales and monitor a part of their habitat long-term.

Arguments in favour of whale watching include the attention it brings to issues of conservation; how it reduces the need for captive whale facilities, like aquariums; and that it provides an opportunity for scientific research.

Arguments in favour of whale watching include the attention it brings to issues of conservation; how it reduces the need for captive whale facilities, like aquariums; and that it provides an opportunity for scientific research.

Whale watching provides plenty of incentives for human beings, but what’s unclear is whether it provides much benefit for the whales themselves.

Conservation

Proponents of whale watching hope that tourists returning from a trip will be changed by the experience. The intention is to educate  people about the plight of whales and encourage them to take action in their everyday lives. This could include cleaning up litter, making donations or supporting conservation policy.

people about the plight of whales and encourage them to take action in their everyday lives. This could include cleaning up litter, making donations or supporting conservation policy.

There are few long-term, in-depth studies measuring the impact of whale watching, or any marine mammal tourism on people who participate. A survey by H. Zeppel and S. Muloin, published in 2008, found that people did make changes in behaviour up to three months after interacting with sea turtles, such as helping to clean local beaches and donating money to conservation non-profits. However, there aren’t many studies like this and the results aren’t conclusive.

In a paper looking at several studies like this one, which rely on people to self-report their thoughts and behaviour, researchers C. Malcolm and D. Duffus wrote, “little research has demonstrated the lasting social or conservation value that is espoused as the overarching raison d’etre for using wild marine mammals as ecotourism subjects.”

Proponents of whale watching hope that tourists returning from a trip will be changed by the experience. The intention is to educate  people about the plight of whales and encourage them to take action in their everyday lives. This could include cleaning up litter, making donations or supporting conservation policy.

people about the plight of whales and encourage them to take action in their everyday lives. This could include cleaning up litter, making donations or supporting conservation policy.

There are few long-term, in-depth studies measuring the impact of whale watching, or any marine mammal tourism on people who participate. A survey by H. Zeppel and S. Muloin, published in 2008, found that people did make changes in behaviour up to three months after interacting with sea turtles, such as helping to clean local beaches and donating money to conservation non-profits. However, there aren’t many studies like this and the results aren’t conclusive.

In a paper looking at several studies like this one, which rely on people to self-report their thoughts and behaviour, researchers C. Malcolm and D. Duffus wrote, “little research has demonstrated the lasting social or conservation value that is espoused as the overarching raison d’etre for using wild marine mammals as ecotourism subjects.”

There are few long-term, in-depth studies measuring the impact of whale watching, or any marine mammal tourism on people who participate. A survey by H. Zeppel and S. Muloin, published in 2008, found that people did make changes in behaviour up to three months after interacting with sea turtles, such as helping to clean local beaches and donating money to conservation non-profits. However, there aren’t many studies like this and the results aren’t conclusive.

In a paper looking at several studies like this one, which rely on people to self-report their thoughts and behaviour, researchers C. Malcolm and D. Duffus wrote, “little research has demonstrated the lasting social or conservation value that is espoused as the overarching raison d’etre for using wild marine mammals as ecotourism subjects.”

In “Managing the Whale- and Dolphin-Watching Industry: Time for a Paradigm Shift,” authors R. Constantine and L. Bedjer call for a burden of proof that whale watching isn’t harmful to be put on the industry, rather than having scientists and environmentalists in the position of having to show harm.

Better than captivity

If seeing whales does help capture the appetites of the public in supporting conservation policy, captive whales are another way for people to get up close. However, keeping whales in captivity is full of ethical concerns.

Given the size of whales and their range of migration, it is next to impossible to provide a facility that meets their physical needs. Because facilities need to be profitable to continue operating, there is also incentive to get the whales to perform—breaching, tail slapping and other behaviours that aren’t fully understood by humans yet, but some researchers believe can be signs of distress. The effects of performing aren’t fully understood either, but there is evidence that captive whales have extremely poor health.

Exposés like the documentary, ‘Blackfish’ and news reports on Marine Land suggest that whales in captivity don’t have enviable lives.

If seeing whales does help capture the appetites of the public in supporting conservation policy, captive whales are another way for people to get up close. However, keeping whales in captivity is full of ethical concerns.

Given the size of whales and their range of migration, it is next to impossible to provide a facility that meets their physical needs. Because facilities need to be profitable to continue operating, there is also incentive to get the whales to perform—breaching, tail slapping and other behaviours that aren’t fully understood by humans yet, but some researchers believe can be signs of distress. The effects of performing aren’t fully understood either, but there is evidence that captive whales have extremely poor health.

Exposés like the documentary, ‘Blackfish’ and news reports on Marine Land suggest that whales in captivity don’t have enviable lives.

Given the size of whales and their range of migration, it is next to impossible to provide a facility that meets their physical needs. Because facilities need to be profitable to continue operating, there is also incentive to get the whales to perform—breaching, tail slapping and other behaviours that aren’t fully understood by humans yet, but some researchers believe can be signs of distress. The effects of performing aren’t fully understood either, but there is evidence that captive whales have extremely poor health.

Exposés like the documentary, ‘Blackfish’ and news reports on Marine Land suggest that whales in captivity don’t have enviable lives.

Whale watching then becomes a healthier and safer alternative to captivity. Humans visit whales on their own turf, where the animals are free to move around and under no obligation to perform.

However, the boats still add to the disruptions of their habitat, bringing thousands of people out on the water each year trying to catch a glimpse.

Science

The tourists aren’t the only ones on the water. Researchers also head out to observe whales, trying to collect research. Scientists benefit from the whale watching industry through the attention to their subjects, giving their work publicity and funding. The Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park houses the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals, making their research possible.

The tourists aren’t the only ones on the water. Researchers also head out to observe whales, trying to collect research. Scientists benefit from the whale watching industry through the attention to their subjects, giving their work publicity and funding. The Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park houses the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals, making their research possible.

According to New England Aquarium researcher Moira Brown, photos of right whales taken by tourists sometimes lead to new survey areas for scientists. For example, tourists took photos of right whales on the Gaspe Peninsula in Quebec in the mid-‘90s, leading to new research in that area.

However, there are limits to the benefits of this research for whales. For one, it’s difficult to make conclusions because there’s very little pre-tourism whale data with which to make comparisons. It’s also difficult to make comparisons because the technology changes often. Beluga population data is inconsistent simply because scientists conduct each survey with completely different technology, depending on what’s available and possible.

The tourists aren’t the only ones on the water. Researchers also head out to observe whales, trying to collect research. Scientists benefit from the whale watching industry through the attention to their subjects, giving their work publicity and funding. The Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park houses the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals, making their research possible.

The tourists aren’t the only ones on the water. Researchers also head out to observe whales, trying to collect research. Scientists benefit from the whale watching industry through the attention to their subjects, giving their work publicity and funding. The Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park houses the Group for Research and Education on Marine Mammals, making their research possible.

According to New England Aquarium researcher Moira Brown, photos of right whales taken by tourists sometimes lead to new survey areas for scientists. For example, tourists took photos of right whales on the Gaspe Peninsula in Quebec in the mid-‘90s, leading to new research in that area.

However, there are limits to the benefits of this research for whales. For one, it’s difficult to make conclusions because there’s very little pre-tourism whale data with which to make comparisons. It’s also difficult to make comparisons because the technology changes often. Beluga population data is inconsistent simply because scientists conduct each survey with completely different technology, depending on what’s available and possible.

According to New England Aquarium researcher Moira Brown, photos of right whales taken by tourists sometimes lead to new survey areas for scientists. For example, tourists took photos of right whales on the Gaspe Peninsula in Quebec in the mid-‘90s, leading to new research in that area.

However, there are limits to the benefits of this research for whales. For one, it’s difficult to make conclusions because there’s very little pre-tourism whale data with which to make comparisons. It’s also difficult to make comparisons because the technology changes often. Beluga population data is inconsistent simply because scientists conduct each survey with completely different technology, depending on what’s available and possible.

Scientists are also often requested to make recommendations without having enough time to get solid data—which could take a quite a long time given that whales live for decades or centuries and breed much more slowly than human beings. Further, when regulations are created, they often don’t take scientific research into account.

Regulating whales

Regulations in the St. Lawrence

At the time of this writing, there aren’t any federal whale-watching-specific regulations in place, although there have been ongoing consultations since 2003.

In a recent statement, a representative from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans said it is “working to conclude the regulatory process,” which is due to conclude by the end of 2017.

In a recent statement, a representative from the Department of Fisheries and Oceans said it is “working to conclude the regulatory process,” which is due to conclude by the end of 2017.

For now, the department includes a set of guidelines for whale watchers on its website, which include slowing down, keeping clear of whales, only approaching them from the side and not interacting with whales. None of these guidelines includes a specific measurement, such as a speed or distance.

Specifics are governed under various other regulations and are stricter within the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park.

“You can’t just buy yourself a whale watching boat in Montreal, put people on it, and then come to the marine park and sell whale-watching tours,” said Galadza-Park, external relations manager of the park. There are only 53 permits for whale-watching boats and they are subject to specific operating regulations (as described in the map below). By keeping the number of boats low, she said, “we’re not going to suddenly have 10 times as many boats on the water because there’s only a certain number of permits.”

The regulations are monitored within the park by wardens and outside the park by the Coast Guard. However, as Beland, a researcher said, “It’s very hard to apply regulations to individuals who are on their own boat and can go out at high speed through the beluga habitat.

“Even within the confines of the Saguenay-St. Lawrence national park, we have lots of observations showing that people crowd the whales, people go too fast, people tend to touch them or get closer, and this is not good for the whales.”

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1Kt7enwE2PvEcZPcorwVX0WVZo6w&usp=sharing

Voluntary or Mandatory?

The St. Lawrence isn’t very big, compared with the sea most whales return to in the fall. But it’s still wide and vast enough that no one can monitor all of the boats all of the time. Because of this, some whale conservationists have been hesitant to call for stronger regulations of whale-human interactions.

In “Slow Down to Save the Whales,” a study published in 2016, researchers write that people are more likely to follow-through on slowing down for whales if they understand how they’re affecting habitats. The study found that giving information about whales and having the Coast Guard request pilots to voluntarily slow down boats could have a huge overall effect on boat speeds.

In “Slow Down to Save the Whales,” a study published in 2016, researchers write that people are more likely to follow-through on slowing down for whales if they understand how they’re affecting habitats. The study found that giving information about whales and having the Coast Guard request pilots to voluntarily slow down boats could have a huge overall effect on boat speeds.

However, voluntary measures tend to lead to inconsistent behaviour. Memorial University researcher Mark Stoddart said, “Within the Newfoundland context where I live and work, what it ends up relying on is the environmental ethic of particular operators and how they decide they should behave without really any code of conduct. You get a range of behaviors.”

Newfoundland context where I live and work, what it ends up relying on is the environmental ethic of particular operators and how they decide they should behave without really any code of conduct. You get a range of behaviors.”

Even in the Saguenay-St. Lawrence Marine Park, where there are specific and strict regulations in place, it’s difficult to monitor human behaviour.

“The challenges that we all have are the fact that there’s no Welcome to the Marine Park sign, please drive through this gate, and we will hand you a brochure, and you give us your entry fee, and you’re very aware that you’re in a marine park,” said Galadza-Park. She adds that even if they know they’re in the park, they may not be aware of the boat regulations.

In the same spirit as the researchers looking at voluntary measures, Parks Canada has invested in education and trying to reach as many people as possible. “We go to boat trade shows and outdoor adventure shows and we’re constantly trying to reach people before they come to our marine conservation area,” said Galadza-Park.

Outside of the marine park, however, without strict whale watching regulations in place, it’s difficult to know how or what the public needs to know.