For Ottawa’s craft brewers, making beer is more often a labour of love than a cash cow.

With high capital start up costs and a market overshadowed by big foreign-owned producers, the road to owning a successful brewery can be treacherous.

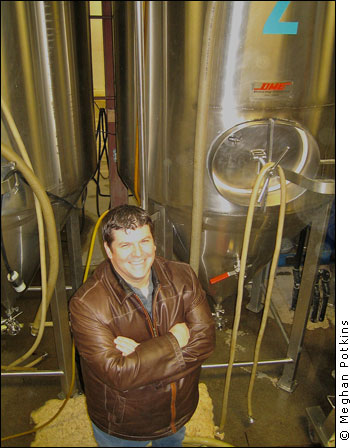

Paul Meek heads a growing Ottawa beer empire.

In a recent shakeup of Ottawa’s community of brewers, Kichesippi Beer Co.’s Paul Meek bought Heritage Brewing Co., Ottawa’s only full-production brewery.

Ron and Donna Moir, Heritage’s owners for the past decade, are retiring from the brewing business to spend time with family and a new grandchild. Picking up where they’ve off is Meek, whose plans for the brewery have invigorated the existing staff.

In just eight months he has gone from being a small contract brewer, responsible only for the marketing, sale and distribution, to a full-fledged beer producer.

Meek comes to the production side of the beer business from a lengthy career on the sales side. Having begun as an Alexander Keith’s sales representative at St. Mary’s University in Halifax, Meek went on to work for some of the big brewers like Labatt and Sleeman, where he specialized in the craft and import beer portfolios.

With the purchase of Heritage in December and more recently the purchase of Scotch Irish Brewing (a distinct company from Heritage that operates out of the same location), Meek has grown Kichesippi exponentially larger— with plans to be on the shelves of the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO), next month.

“I never thought we would be owning Ottawa’s only full-production brewery within eight months,” says Meek. “We’re very happy it worked out that way [but] it was definitely a little quicker than we had anticipated.”

Contract brewing

Heritage has been Ottawa’s only full-production brewery since it started in 2000, but there are other craft brewers in the city including the small but productive Clock Tower Brewpub downtown and Hogsback Brewing Co.

Like many craft brewers, Hogsback brews its beers under contract with another full-production brewery. Allowing someone else to make the beer for you can be useful when you’re beginning in the beer industry. Without any of the responsibilities of production, contract brewers can focus on the other side of the business: marketing, sales and distribution.

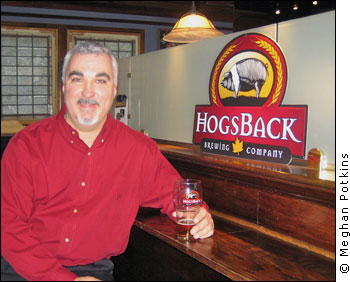

Paige Cutland, co-owner of Hogsback, got into the brewing business last spring with three old friends, most of them having shared an early career in the Air Force.

Paige Cutland, co-owner of Hogsback, promoting his products in Ottawa pubs.

For the time being, Hogsback is only a part-time venture for Cutland who works in high tech. He says that when he and his business partners set out to create Hogsback, they had intended to build a brewery of their own as soon as possible.

On the advice of former Sleeman president Doug Berchtold, Cutland and his partners decided to go the contract-brewing route for the first couple of years. Hogsback tapped Toronto’s Cool Beer for the contract, in the hopes that down the line it will be in an even better position to build.

“[Contracting] allows us to build our business, so that when we actually do want to commit that capital to building a brewery, we’ll have a revenue stream,” says Cutland.

“We’ll have a business model…we’ll have lots of customers. We’ll be able to go to the bank and borrow that much more money than we could have a year ago when we had nothing but a business plan.”

Hogsback has its Vintage Lager in 18 LCBO locations in the Ottawa area and developed a substantial base of restaurants and pubs carrying its draft.

With plans in the works to build their own brewery by next year, for the time being, Hogsback will continue to sell its Toronto-sourced product under a local name.

Battling the big guys

Besides the expense of producing the product, small batch brewers like Hogsback and Kichesippi are at a disadvantage when soliciting bars and restaurants to carry their beer.

“The challenge was growing our base of licensees that carry us on draft,” says Cutland. “That was the bit that we probably underestimated.

While major producers like Molson and Labatt can afford to offer vendors discounted or free promotional materials, small brewers rarely have the budget to offer similar inducements.

It is not uncommon for big producers to lure bars and restaurants with offers to provide free advertising materials or to sponsor a menu-redesign. In return, vendors agree to carry the product— or even to offer the brand exclusively.

“We don’t have the economies of scale in terms of our cost per litre to put out the beer [like] Molson and Labatt,” says Meek. “And therefore we don’t have that money left over from a batch to create those marketing programs.”

Then there is the challenge of getting their beer onto shelves at the LCBO or stocked by The Beer Store.

Many small brewers contend that the private owners of The Beer Store— international brewing giants Anheuser-Busch InBev, Molson Coors and Sapporo— have imposed retail and marketing policies that adversely affect the sale of craft brew products.

Distribution blues

According to Meek, the biggest difficulty for small brewers in Ontario is distribution:

Meek says that large brewers can put their beer on big 18-wheel tractor trailers and take it to The Beer Store or the LCBO and distribute it through their respective warehouse systems.

“We don’t have the volumes to work with those warehousing systems. We need to be somewhat inefficient…to get to market,” says Meek.

Heritage is Ottawa’s only full-production brewery.

Heritage is Ottawa’s only full-production brewery.

According to statistics gathered by the Ontario Craft Brewers association, between three and five breweries enter the Ontario market each year and at least one or two of those will fail.

For new brewers like Kichesippi and Hogsback, the cost of equipment, marketing and raw materials can pile up—especially in the early stages of the business.

“The running joke in the craft beer industry is that if you want to make a small fortune in the beer world— you start with a big fortune,” says Meek.

Despite the challenges, this is a business characterized by strong emotional attachments.Many of Ottawa’s brewers are in business with friends and family, leaving behind more conventional careers in the high-tech sector or government— and all of them are beer lovers.

“It’s called craft beer because it is in art,” says Meek. “It’s really hands on and we take the time to make sure the product really is cared for.”