New York University professor Andrew Ross once wrote that “the smallest bookstore still contains more ideas of worth than have been presented in the entire history of television.”

Having passed through the “Great Recession” relatively unscathed, Ottawa’s small, independent bookstores are facing an uphill battle, but television isn’t the enemy.

NOT A NATIONAL CHAIN

The Goliath staring down the city’s last remaining independent bookstores is what one store owner calls the “nexus” of predatory pricing at big-box retailers, shoppers turning to the Internet for better deals and the emerging threat of e-books.

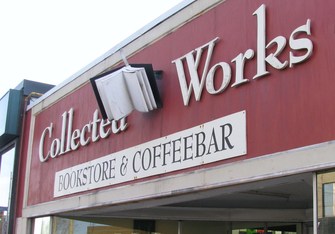

When Christopher Smith opened Collected Works Bookstore and Coffee Bar, in Westboro, in 1996, it was a dream come true. After toiling for years in other people’s bookstores, he now had the freedom to choose what books he would put on his shelves and, at the end of the day, could sit back and enjoy the fruits of his labour. Those fruits, however, are rather scarce in the book-selling world.

“You don’t open an independent bookstore to make a fortune,” says Smith. He accepted this inevitability when he opened the store with his partner, Craig Poile, who works as a technical writer to supplement their income.

Despite meager profits, Smith says the Canadian book-selling industry, and independent bookstores in particular, weathered the recession quite well.

He says the book market as a whole grew by between one per cent and two per cent in Canada over the course of the recession. Sixty per cent of independent bookstores enjoyed some growth; twenty per cent saw a drop in sales and the remaining 20 per cent of stores had sales that were unchanged from the year before.

BUCKING THE TREND

This slight growth in the Canadian market is in stark contrast to the four per cent drop in sales at U.S. bookstores last year, a sign says Smith, of an overall decrease in reading generally in the United States.

“You couldn’t say the recession affected independent bookstores, per se,” he says. “During a recession books are a cheap form of entertainment and reading material is good value for money.”

One of independent bookstores’ biggest threats comes from big-box stores, such as Costco, where a hardcover copy of Dan Brown’s mega-bestseller The Lost Symbol sells for $16.99. The same book sells at Collected Works for $36.95

Web sites like Amazon.com are equally dangerous, says Smith. “Amazon encompasses everything: the discounting, the U.S. pricing, online retailing, the Kindle. Amazon is one of the biggest threats to brick and mortar stores.”

He says the threat of e-books is negligible, for the time being. Accounting for just 0.04 per cent of the book market as a whole, the sale of e-books is growing by 1,600 per cent a year, he says.

“When you ask a customer what their preferred format is, less than 20 per cent say it’s an electronic format. If they could buy a hard copy book for the same price as an e-book, they would. People turn to e-books because of the price point,” says Smith.

Laura Rayner, the co-owner of Mother Tongue Books, in the Glebe, says the recession didn’t have much of an effect on her store although, “sales were not that great to begin with.” She agrees with Smith that opening an independent bookstore is not a huge profit-making endeavor and says she’s “just happy to eke out a living.”

Mother Tongue benefits from its proximity to Carleton University, and “relies on the kindness of professors who order the reading material for their classes through our store,” she says. Mother Tongue also enjoys the added advantage of having a “theme”. The store has long been recognized as a “woman’s bookstore,” says Rayner.

COSTCO THE THREAT

Although she says electronic devices like the Sony Reader, Amazon’s Kindle and Apple’s new iPad have yet to take hold, “the publishing industry, when it insists on underselling to places like Costco, is really hurting bookstores, to the point that the anticipated releases of big titles just don’t matter as much as they used to.”

She says the big question now is what happens with Google and its plan to digitize millions of book titles. “People want things for free and this means brick and mortar stores are going to become less and less appealing.”

She does see a silver lining, however. The growing irrelevance of bookstores will invariably force big chains, such as Chapters and Indigo Books and Music, to shut down some of its stores, perhaps paving the way for resurgence in independent bookstores like Mother Tongue.

Kim Ferguson will soon be celebrating the fourth anniversary of her children’s bookstore, Glebe-based Kaleidoscope Kids Books. She says she’s experienced a small but steady growth as she builds up her customer base and Christmas sales, the highpoint of the year for any retailer, were about the same during the recession.

“We’ve noticed that more people are using the library and some people are buying fewer books but the store is still busy, especially when people come in for birthdays and at Christmas,” says Ferguson.

Diane Walker began at Leishman Books, in Westgate Shopping Centre, as an assistant manager in 1979 and is now co-owner, along with Sally Hawks. Their store, just like many others in Ottawa, suffered through first a crippling transit strike in the winter of 2008-09 and then the recession. “We all know that sales are not very good right now,” says Walker. “Selling is harder to do every day with people cutting back on buying books.”

She says book publishers are themselves taking hits and are reluctant to send large shipments of books to stores which could be on the verge of closing down.

“Publishers are cutting off their own heads,” she says in reference to the practice of shipping bulk orders of a single title to stores like Costco. “Those big-box stores only order what they know they can sell a lot of. They’re not interested in stocking an author’s older works and they’re not in it for a love of literature or to support authors.”

Walker says being located in a mall has become something of a curse, with customers walking into the Shoppers Drug Mart next store to buy books for 30 per cent off. “On top of the predatory pricing, we have to cope with paying high rents. We’ve really cut everything we can; we’ve slashed salaries and we’ve reduced the number of copies we order from publishers. We just have to hope that people start buying books.”