By: Koyuki Hayashi

Throughout the various COVID-19 lockdowns of the past few years, Pascale Hodrog spent her free time shopping for skin care products.

Because she wasn’t going out in public much during the lockdowns, the 24-year-old Ottawa woman took the opportunity to experiment with new products that might alleviate her skin sensitivities. For years, she had been dealing with acne and rosacea.

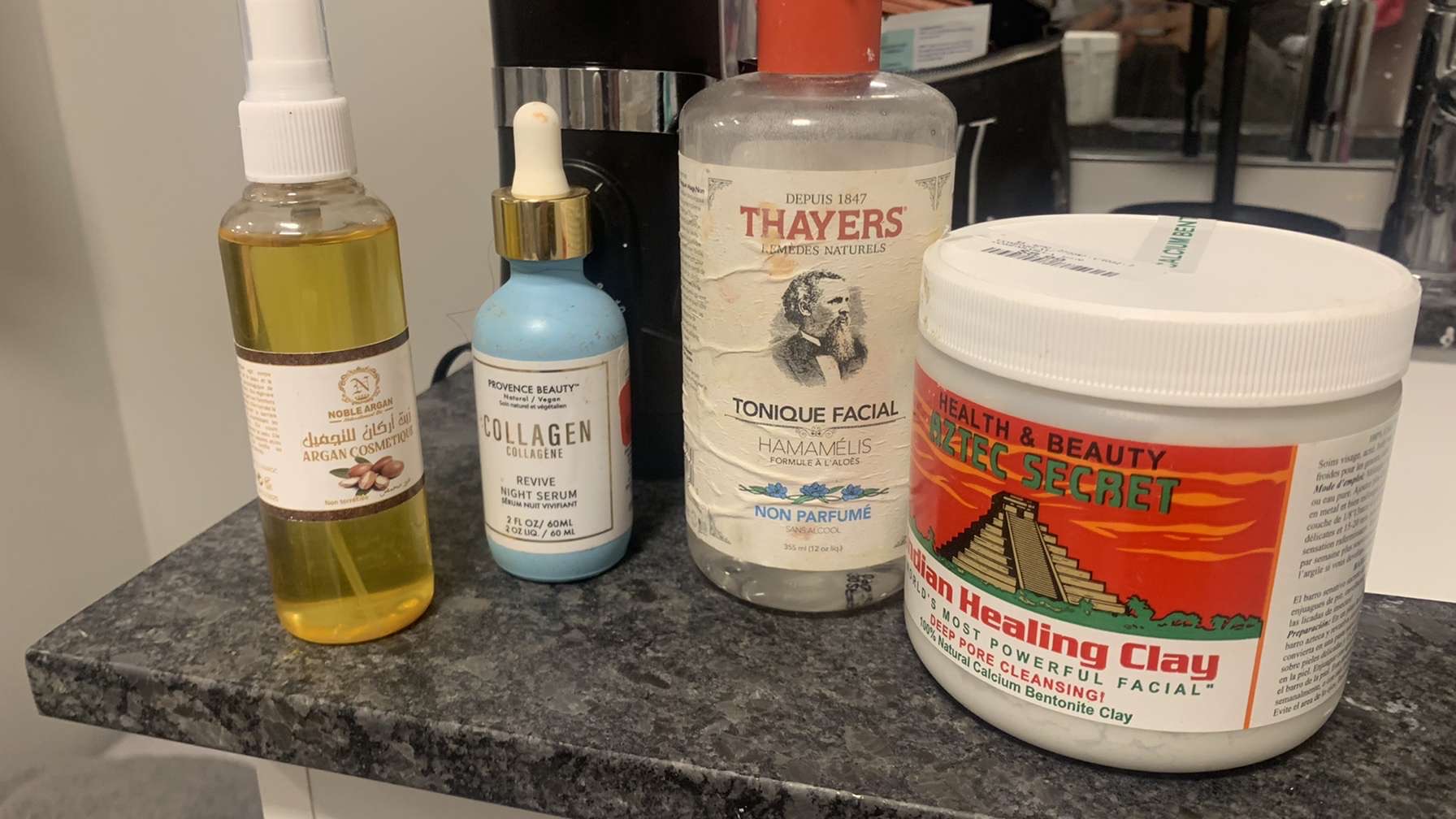

“I bought a lot of random products,” the Carleton University industrial design student says. “I didn’t even know whether they were good for my skin or not and just experimented.”

The experiment worked.

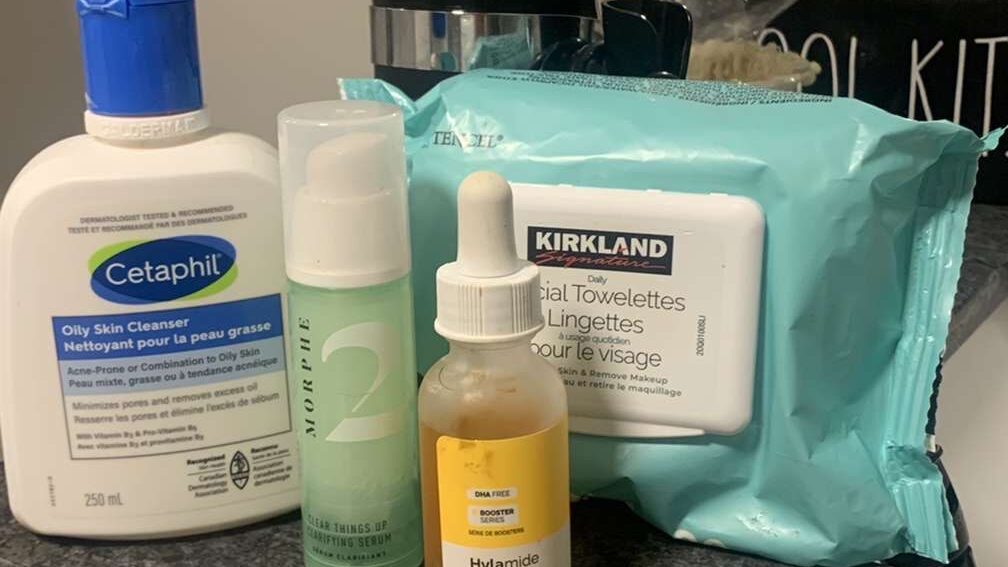

Hodrog says she’s seen a “big pattern change” in her skin care routine and, as a result, has vastly reduced the number of toners, masks and moisturizers in her skin care cabinet. These days, Hodrog says she only uses three products that are “high-tech and pharmaceutical” due to her sensitive skin.

“My skin care now has literally just been water,” Hodrog said with a laugh. “And maybe a medical soap that I use specifically for my skin.”

Hodrog said she is now focused on her skin health and turns to an aesthetician for consultations.

She is not alone.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many Canadian consumers reevaluated their needs regarding skin health. Many people who had previously bought skin care products – often without understanding whether they were actually good for their skin – took the pandemic as a chance to experiment with their skin care routine and achieved their personal “perfect skin” results with far fewer products.

It is a trend dubbed “skinimalism” and it has taken over Canada.

Consumers are shifting to more specific natural products that suit them personally. These days, people aren’t buying as many products as before and opt for specificity instead, according to the Italian Chamber of Commerce in Canada. However, the business database Statista forecasts the skin care market will expand and have a surge in purchases of skin care products. But as the trend grows, some wonder if it is inclusive of people of all ages and cultural backgrounds.

Skinimalism in Canada

Coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic, Canadian consumers like Hodrog changed their skin care routines by ditching the “ten-step skin care routine” and embracing skinimalism, a global beauty trend popularized earlier this year, according to Sophie Shaw from CNN. The beauty trend encourages consumers to take a minimalist approach to their skin care routine. The term was first coined on social media platforms TikTok and Instagram in 2021 when British Vogue editor, Tish Weinstock, interviewed skin care experts who predicted the skinimalism trend growing.

Skinimalism promotes the idea of achieving “clean and healthy” glowing skin by using a few products that contain natural ingredients such as retinol, hyaluronic acid, niacinamide, vitamin C, ceramides, peptides, BHAs and AHAs. These products are promoted by skin care YouTubers and influencers such as Hyram Yarbro, Susan Yara and James Welsh.

Canadian skin care consumers like Hodrog’s pursuit of skinimalism is one of the many experiences that contribute to the rise in popularity. The societal shift to an emphasis on self-care as a beauty trend was heavily influenced by Hodrog and other Canadians’ experiences during the COVID-19 quarantine. Hodrog says she saw the quarantine as a chance to “reset and recharge.”

Before skinimalism became a trend in Canada, the research report Market Analysis: The Canadian Cosmetics Industry indicated the earliest signs of consumers considering the skinimalism lifestyle. In June 2020, the report said cosmetic companies saw a “higher demand for sustainable and natural products among young consumers” and “Canadian consumers remaining loyal to skin care brands, but willing to try new products,” which are key features of skinimalism.

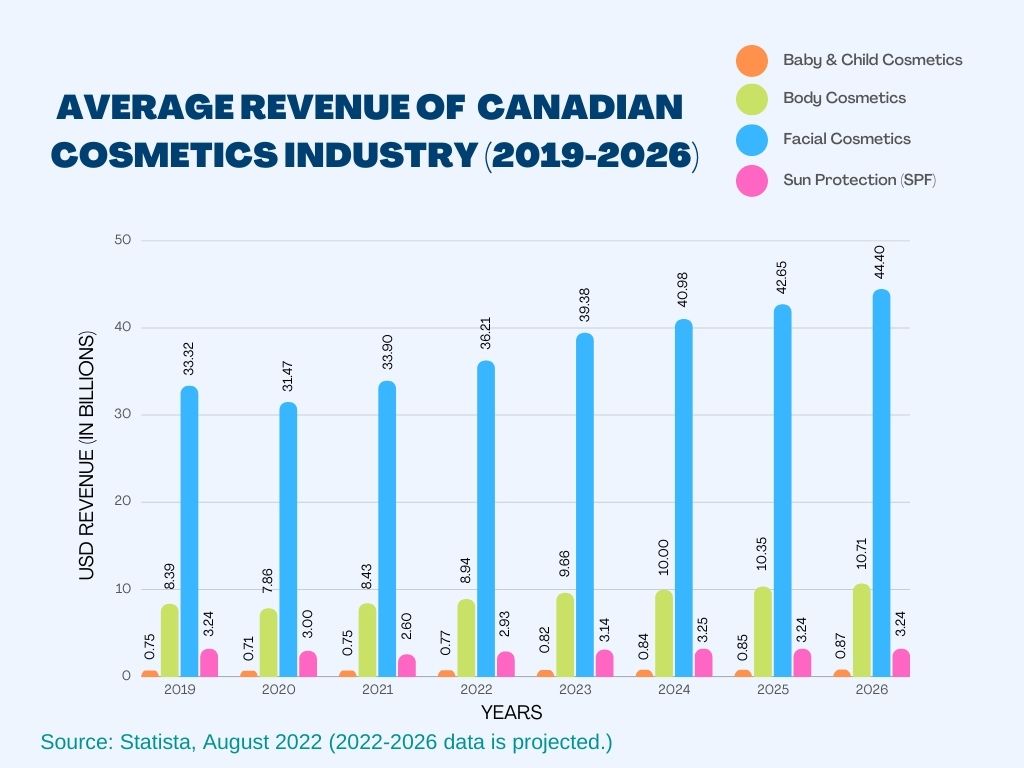

The report stated skin care products have the highest percentage of the total revenue of the Canadian cosmetics manufacturing industry with 37.2 per cent, compared to other beauty products, and that facial skin care products remain the highest-demand beauty commodity.

The skinimalism trend this year in Canada led to surging demand for companies to produce products for specific target markets. According to Statista, researchers forecasted that in 2022-2026, the revenue for the skin care market in Canada will exponentially increase. This year, the Canadian cosmetics industry earned approximately $1.8 billion USD, with 74 per cent of the sales coming from facial skin care products.

Non-cosmetic companies have caught on to the trend and are seeking ways to benefit. For example, on Nov. 9, DoorDash announced its partnership with Sephora to deliver beauty products from all Sephora stores across Canada.

Skinimalism as a self-care, lifestyle

Briar Lee is an Ottawa-based aesthetician who has worked in the profession for eight years. The 25-year-old said she and her colleagues have noticed a shift in attitudes towards skin care. Lee said her clientele have shifted towards a “self-care type of perspective.”

“People are a lot more open to indulge in skin care and finding a way to pamper themselves,” Lee says over the phone.

In 2021, when skinimalism was first talked about in Canada, Canadian consumers spent an average of $252.55 per person on beauty and personal care. She believes Canadian consumers spend more than the suggested $250 a year on personal care, since services such as facial massage and spa treatments are included in this category.

Lee said the needs of different clients vary.

“You will have clients who will get their basic cleanser, moisturizer and toner that would last them for six months before they could purchase it again,” Lee says. “Then you have people like me where I like to have a couple of cleansers, moisturizers and serums … A majority of the clients including me spend over $500.”

Lee says the skin care market is “leaning into different types of directions” and that “specific skin care products are being marketed towards different types of people.”

Youth calling out ‘ageism’ in Canadian cosmetics industry

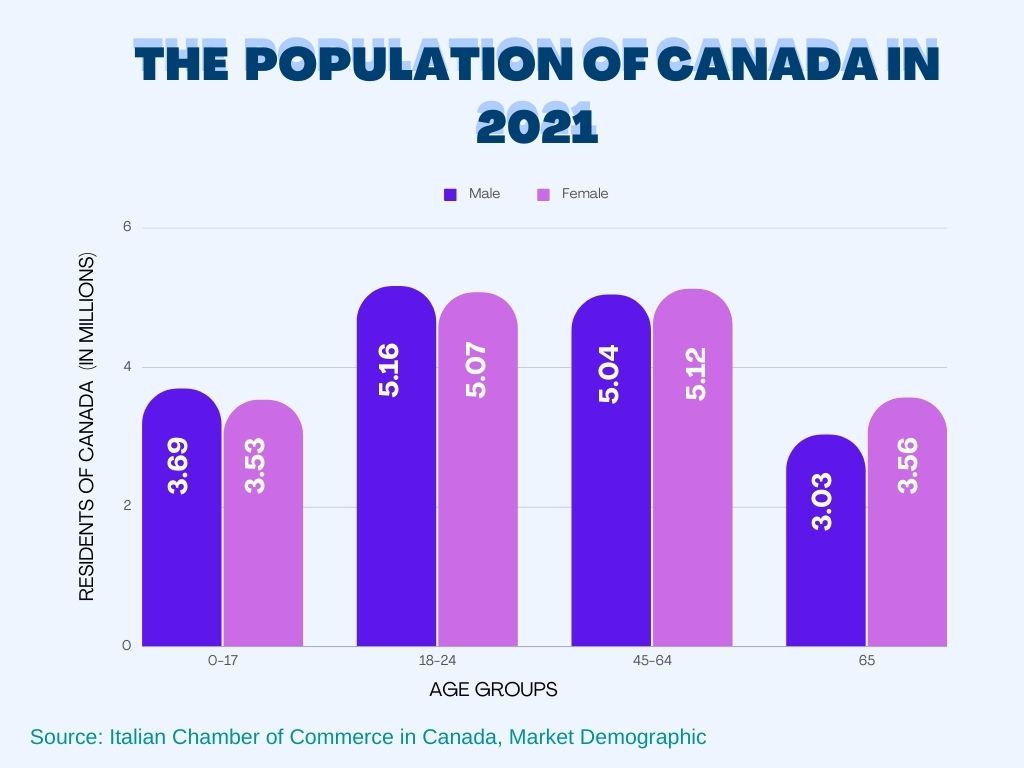

Skinimalism is trending in Canada because the Canadian cosmetics industry is starting to experience a generational shift as the younger population of Canada is entering in the skin care market as consumers and workers. The Italian Chamber of Commerce in Canada stated that Canada overall experienced high demand for skin care from “Generation Z,” which is defined as youth between the ages of 18 and 24. In 2021, generation Z accounted for 10.2 million Canadians, which is 27 per cent of Canada’s population.

Sam Walker, 18, said he used to wear a lot of makeup before the pandemic hit. Now, he follows the skinimalism lifestyle. Walker says he used to watch skin care content on TikTok during the pandemic, but stopped watching after he consulted a doctor.

“I didn’t like all bulls— that I was getting told,” Walker says. “I used to watch skin care videos a long time ago and I felt like it was trying to sell me something more than trying to inform me.”

Influencers on social media are misrepresenting their products, he adds. He says skin care companies are “ageist” because influencers depict “perfect skin,” which is unrealistic and unattainable, especially for older generation Canadians.

Amina Mire, an associate professor of sociology at Carleton University, researches anti-aging and beauty discourses. She said “beauty is now branded as a form of youth and wellness.”

Mire said the issue with ageism in beauty is illustrated by CTV’s controversial decision to fire Lisa LaFlamme. Mire said that Lisa LaFlamme, the network’s longtime anchor, is one of the “casualties” of the pre-pandemic beauty trend which was fixated on anti-aging because middle-aged people, especially women, have the difficulty to “mask their visible aging signs in public.”

Calls for skinimalism to be more culturally inclusive

Concerns about inclusivity in the skin care industry extend beyond ageism.

Sarah May, who works at Toronto Plastic Surgery in the Greater Toronto Area, said both her elderly and young clients are interested in having a “nice glow” to their skin. May says she is interested in the skinimalism trend because she is surprised to hear people are interested in having dewy skin when she has naturally oily skin and wanted to have “matte” skin texture.

May says was disappointed by the lack of inclusivity the skin care market has towards people like her who are prone to acne. But more importantly to her is the industry’s lack of cultural inclusivity towards people of colour. “I feel like most products are catered toward Caucasians because there isn’t enough research that has been done on people of colour,” May says.

Among those filling that void is Dr. Vanita Rattan, a dermatologist of South-East Asian descent who created a skin care line specifically for people of colour, which she promotes on YouTube.

Rattan, who has 715,000 subscribers on YouTube, makes skin care video content targeted at audiences who have different colours of skin. “If you are more likely to tan rather than burn in the sun, then you are considered to have a skin of colour based on the Fitzpatrick scale,” she says in a video titled Skin of Colour (Black or Brown Skin).

May’s concerns about the lack of cultural inclusivity is also seen in the Well and Good article where the dermatologist Dr. Caroline Robinson stated that communities of colour have been left behind in the skin care industry.

Robinson says most women suffered from hyperpigmentation and, in a survey of 2,000 women, 63 per cent of women of colour feel “ignored” by the industry, and that “there aren’t enough effective products for them.”

The rise of skinimalism and the lack of cultural inclusivity in the Canadian skin care commerce is critical because Canada’s 2021 population stated that 22.3 per cent of Canadian residents identify as people of colour.

Mire, who identifies as a woman of colour, says “every woman is pressured to fit into the definition of beauty by using products that are designed for five or ten per cent of the global population.”

“The leaders of the cosmetic industry have a strange and narrow view on what skin is beautiful and then they copy this a million times,” said Mire.

The university professor said she was interested in researching the lack of cultural diversity in skin care when she was a graduate student. Mire recalls when she was a graduate student, she was terrified to hear a lot of black women “bleaching their skin to have less melanin with products that contain mercury and toxic substances.”

Mire adds the definition of skinimalism needs to be clarified to Canadians because the term does not automatically translate to “whiteness” and “anti-aging.” In fact, she says beauty as wellness is the new norm in Canada.

“Beauty is now about wellness, it is not about glamour anymore,” Mire says. “The beauty industry is now a part of the health industry.”