By: Chris Edwards

Lansdowne Park residents are about to receive a spirited new neighbour: a Fire & Flower Cannabis Co. outlet will be opening on Marché Way in the spring. If next year is too long for them to wait, they can currently visit One Plant, another cannabis outlet, about 75 metres away on Bank Street.

If they dislike One Plant, they can walk two blocks north to Superette Cannabis Store. Or keep going, and hit The Good Cannabis Company on the next block. If that store still isn’t for them, they can walk another 30 metres and arrive at High Ties Cannabis Store at the intersection of Second Avenue and Bank Street.

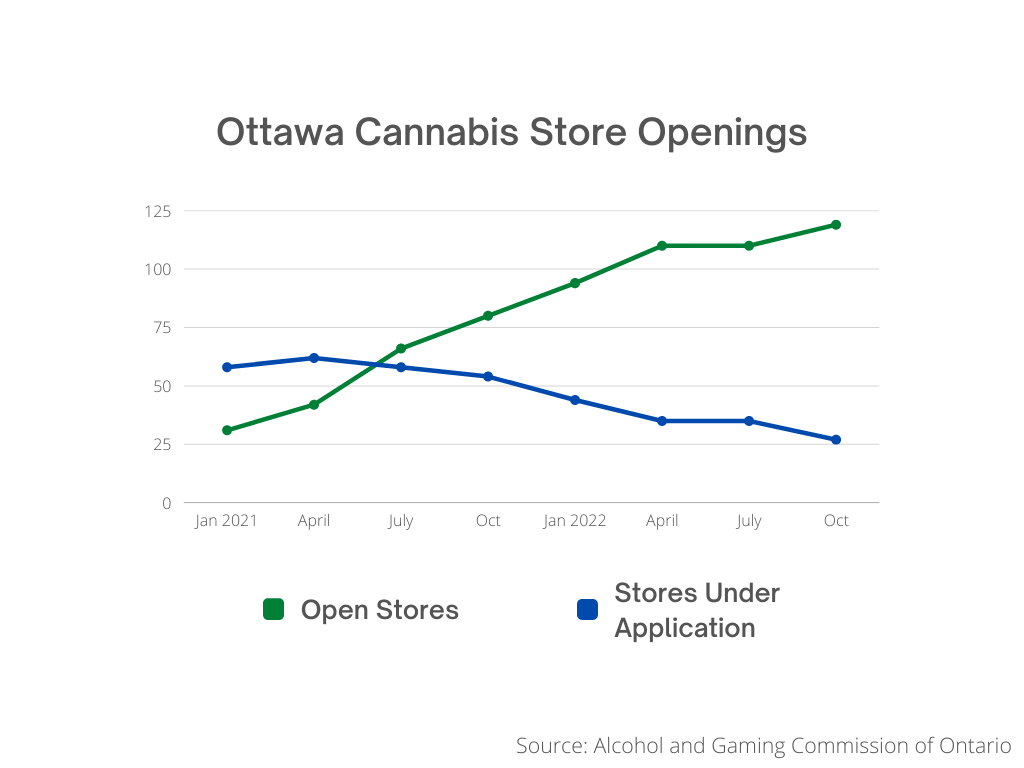

In less than three years, the number of retail cannabis outlets in Ottawa has grown from seven to 119. And that’s not including the ones still on the way, which will bring the total to almost 150. They now outnumber liquor stores roughly three-to-one, and are a common sight in all corners of the city.

But provincial data shows average revenue for cannabis stores saw a 60 per cent decline between 2020 and 2021. Total demand continues to grow, but the customer base has been split up by dozens of new store openings.

It is not clear what the fate of most of these stores will be. Shawn Menard, the city councillor for the Capital Ward, which includes the Glebe, wishes the city had more power to decide how many shops showed up in his neighbourhood.

“We are worried about potential store closures that may follow if the market cannot support all of them,” he said in a written statement provided by his office. “We don’t want to see a number of vacancies on our main streets.”

Menard is not alone in these concerns. Store workers and business leaders acknowledge the clustering of cannabis dispensaries in downtown areas has split the market. Two years after retail stores began flooding Ottawa’s streets, businesses are accepting the reality that consolidation is inevitable, but who will survive remains unclear.

The launch of a new era

The Canadian government officially legalized recreational cannabis in October 2018, but the opening of physical stores was delayed to give regulators more time to prepare.

Provincial governments are responsible for regulating interior store requirements, marketing and where stores can be located. The Ontario government has not imposed any limits on the number of stores that can be opened in a given region. Besides being able to opt out of hosting them entirely, cities do not have the ability to regulate the stores.

The Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario, responsible for licensing cannabis stores, first granted a small number of retail outlets licenses to open the following April. Though it wasn’t until December 2019 that it announced it would begin fully accepting retail store authorizations in early 2020, which opened the floodgates to the retail market.

At the start of 2020, the AGCO was approving five new store licenses per week. By the end, it was processing 30 per week. That year the number of approved outlets in Ontario jumped from 53 to 572, and was only starting to pick up steam. A spokesperson for the AGCO confirmed that as of November 2022 there are 1,615 licensed cannabis stores in the province, with another 300 on the way.

The Glebe will soon be home to five cannabis stores, while four are currently operating along a small stretch of Bank Street in Centretown and another five are clustered in the ByWard Market.

A bold new presence

Christine Leadman is the executive director of Downtown Bank, Bank Street’s business improvement association. She is worried about the rapid growth of stores.

“Our concern is an over proliferation of any one type of business,” she said in an interview. “It’s not a healthy environment. If it’s not diverse enough it doesn’t attract pedestrian movement.”

Coun. Menard feels similarly about the stores in the Glebe. “Currently, cities do not have the authority to regulate these stores,” he said in a statement. “We believe cities should be given limited powers by the province to better manage the growth of cannabis stores while the market matures and settles.”

Leadman said she is happy with how the retail industry has evolved with legalization. “With the first group, when it wasn’t legal yet, it was like a free for all,” she said. “It wasn’t professional, it was poorly managed, and it encouraged a type of behaviour that really created problems on the street that we haven’t seen at all under the new regulations.”

Despite hosting four cannabis stores, Leadman’s association has not received any complaints about them from community members or business owners. Stores are strictly regulated and are routinely inspected by AGCO officials.

Leadman says she wishes there would have been more regulation in place to control the number of stores before they came in, but now that they’ve arrived, the market will level out and “do its own correction.”

A waiting game

Now with 119 stores in Ottawa, the lucrative era for the city’s first dispensaries has given way to an aggressive period of competition.

“A lot of people made a lot of money early on,” said Elliot Wickham, who has worked in the industry for several years, and now works as a budtender at One Plant in the Glebe. By his account, the first stores that opened captured the entire market. “But then more and more opened, and you split your customers,” he said.

“It’s literally just knuckling down and getting more and more investors so that they can stay open.”

Wickham has seen the effects of high competition first hand. He used to work at Plateau Cannabis, also in the Glebe, which folded because it could not meet payroll.

In order to understand the full picture of the retail market, it must be seen in terms of the independent stores holding out against the more financially powerful chain locations. Those chains have the money to support unprofitable outlets, while the independent stores don’t. Less than a quarter of Ottawa’s dispensaries are independently owned.

One Plant is one of these chains. It has over 30 stores in Ontario and has plans to open another 65. Wickham said he was confident it would outlast other stores.

Elliot Borer works down the street at The Good Cannabis Company, the only independent cannabis store in the Glebe. “[A lot of companies] rushed into it,” he said. “It was chains saying ‘Well, we have money, we might as well open up another store’ and not thinking through the area and what it would take to stay in business there.”

Borer thinks his store offers a more personal cannabis experience. “Cannabis users have always been a bit counter cultural,” he said. “I feel like most users don’t want to shop at a place like One Plant because it’s so impersonal,” he said.

High Ties Cannabis Dispensary is about 60 metres down the block from The Good Cannabis Company. Like One Plant, it has multiple locations across eastern Ontario.

Matthew Hamman is the spokesperson for High Ties. Naturally he feels confident about the success of its Glebe location. He welcomes the competition brought about by the high number of dispensaries in the neighbourhood, likening them to the Glebe’s high number of coffee shops, which afford customers more variety and fosters competition. From Hamman’s perspective, the greatest benefit of all this competition is for the consumer.

“It’s been nice to be pushed out of the nest a little bit with regards to creativity,” he said. “We like where we’re at, but we’ll adapt.”

High Ties also price matches, which is a common practice among the Glebe’s stores. “I feel confident about our ability to compete against the other dispensaries,” he said.

But the fate of High Ties and its competitors remains to be seen. New store growth in the city has hit a plateau, with only nine new outlets having opened since March. It’s now a waiting game where, in the words of Wickham, “everyone’s holding out until someone else crashes.”