By: Rey Zinck

When Josh Greenberg bought a collection of used vinyl records this fall, he found more than worn albums inside.

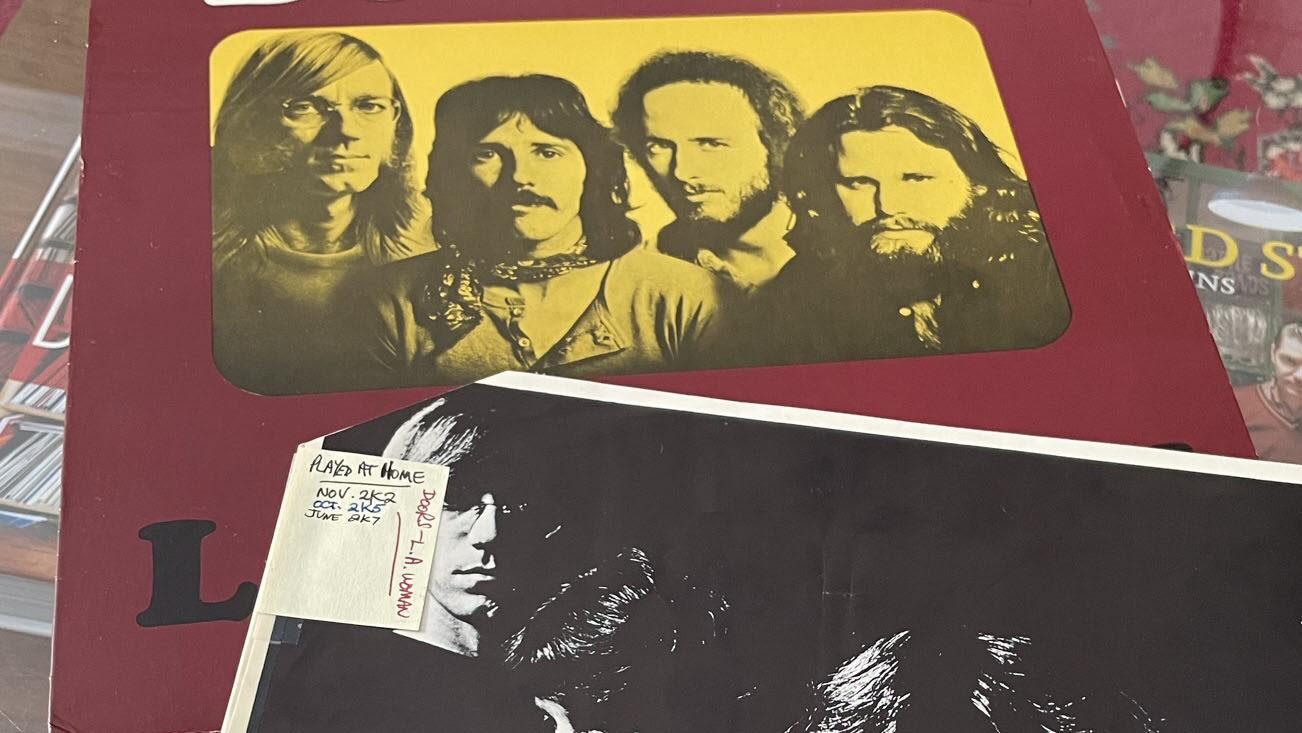

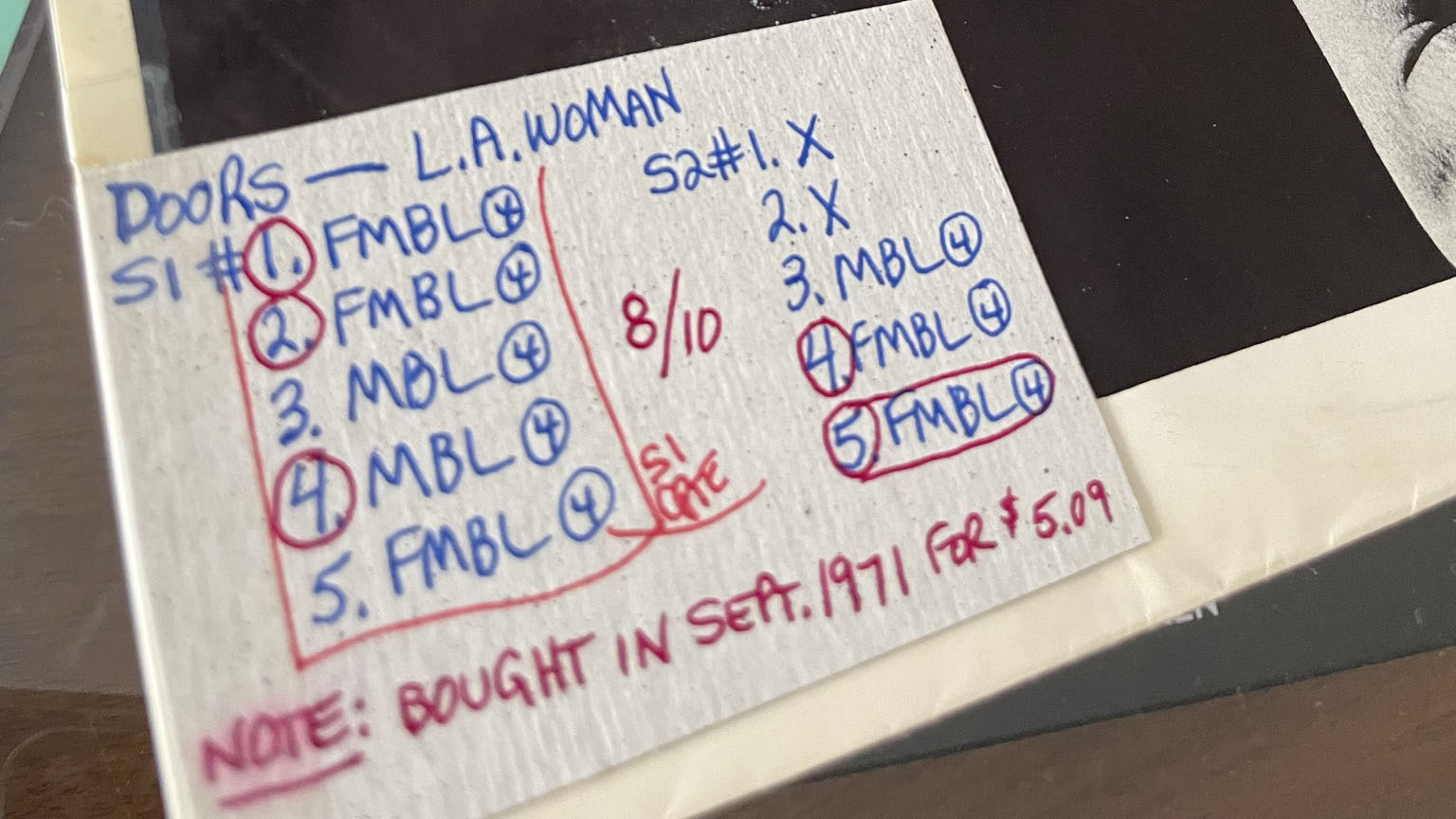

The long-time analog music collector and Carleton University media professor opened his used copy of The Doors’ LA Woman to discover annotations from the previous owner dating back to 1971.

The notes, stuck to the record’s inner sleeve, explained when the original owner bought and played the record, how they felt about it and where they played it in their house.

“I had this strange connection to this person I had never met before through the notes they left about their record,” Greenberg said. “I wasn’t buying a used record at a store; I bought that guy’s collection: a bunch of records that belonged to him that were part of his history and his experience. …

“It’s interesting in a way that no digital format could afford.”

While Greenberg is one of a small but devoted cult following that has stuck with vinyl over the last few decades, record stores are seeing a new generation of collectors sifting through the stacks, breathing new life into a nostalgic hobby that peaked in the 1970s. Despite digital media saturating the music market, the demand for analog is only increasing.

Proponents of the vinyl revival, including store owners and collectors, say it has an element of human connection other mediums lack. The desire for media that is tangible and engages all five senses is now driving record sales in a way that hasn’t been observed since the 1990s.

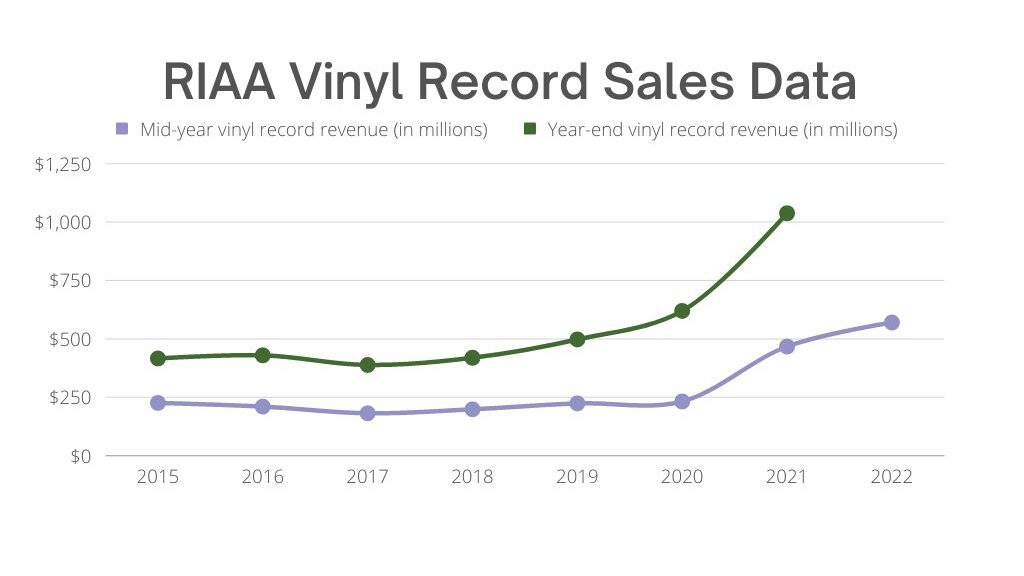

A surging market

Based on data from the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), vinyl record revenues shot up by 94 per cent in the first half of 2021 compared to the first half of 2020. They reported continued growth in the first half of 2022.

The Canadian Press reported that 1.1 million vinyl records sold in Canada in 2021, breaking the 2019 record of 1.03 million records.

Ian Boyd has owned the record store Compact Music on Bank Street since 1991. He said he has seen record sales climb in the last few years.

According to him, streaming services became mainstream in Canada around 2012, prompting customers to abandon their CD players and turntables altogether.

“2013 and 2014 were the toughest years probably since I had opened,” he said.

Then in 2016, Boyd said record sales started to pick up with Adele’s 25 and Jack White’s Acoustic Recordings 1998-2016 and have continued to grow since.

“It’s a very exciting time to come and work in the record business,” he said.

Though the resurgence of vinyl predated the beginning of the pandemic, Greenberg and Boyd both said that the COVID-19 pandemic helped accelerate it.

Boyd said when people couldn’t attend concerts, listening to vinyl was the next best thing.

“Unlike other activities that you really can’t do during lockdown, listening to music is something you can do,” Greenberg said.

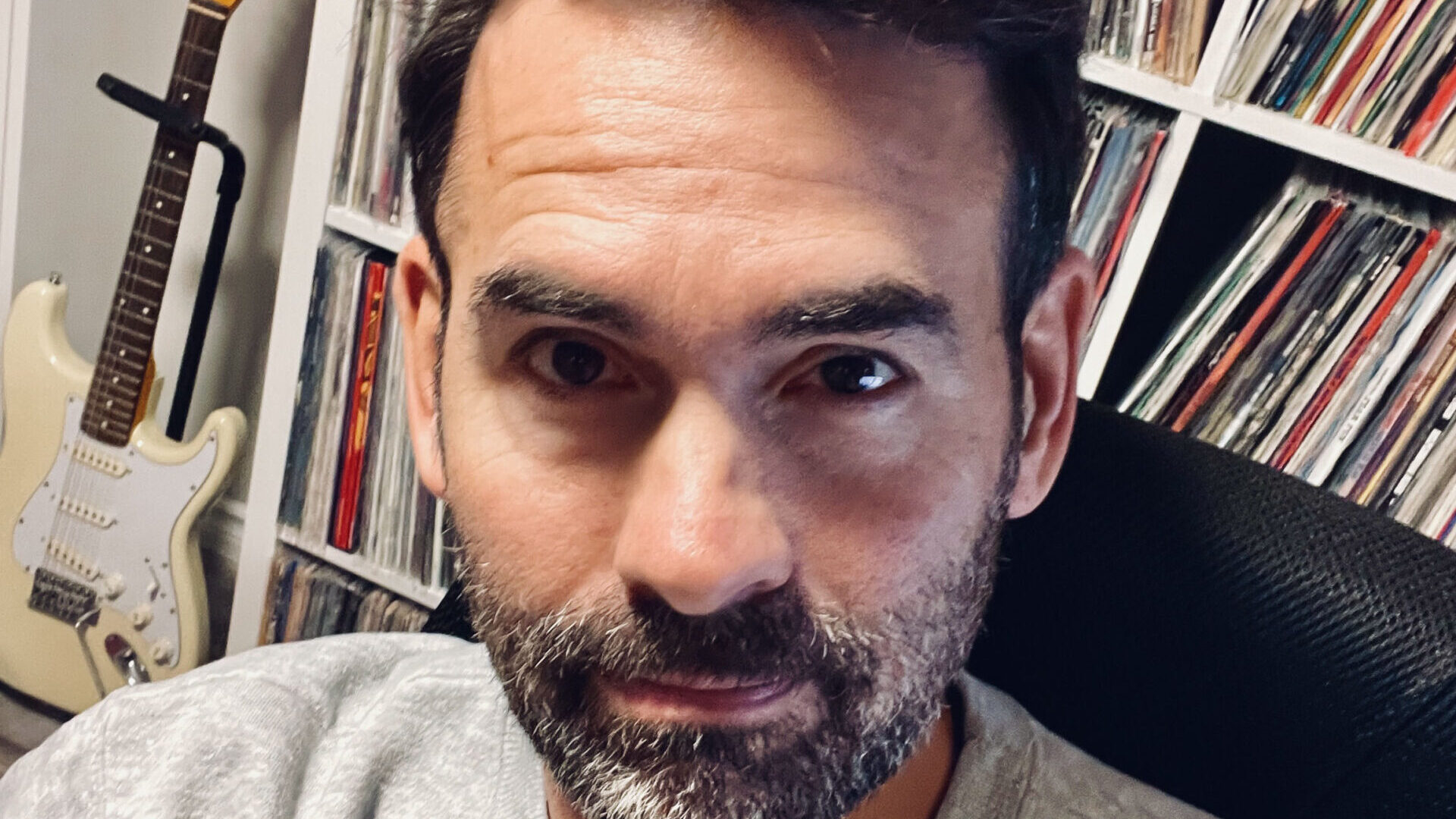

Greenberg’s current research looks at something he calls “vinyl culture,” which includes the history and experiences of record store owners and their patrons.

According to Greenberg, record collecting has historically been dominated by men between the ages of 25 and 50. However, his research suggests the new wave of record collectors looks a bit different.

“The shop owners I’ve spoken to refer to a more diverse consumer population,” Greenberg said. Namely, more women and young people are getting into it.

Boyd said selling records now dominates his business, and he sees young people in the store looking at their phones with their Spotify apps open as they decide what to buy.

“We have kids coming in who are walking in with the same sense of excitement that we walked into record stores with when we were their age.”

Billboard reported that Taylor Swift’s Midnights sold over 400,000 vinyl copies worldwide in its first week of release this October, shattering the record for single-week vinyl sales since 1991.

“Taylor Swift is an incredibly important artist for the record business,” Boyd said, adding the artist has brought younger people into the record stores.

Collecting to connect

Alexa Elser, 28, began collecting records 10 years ago after finding some of her dad’s old vinyls in their garage. Since then, she has accumulated around 100 vinyl copies.

For Elser, collecting used records is interesting because of each record’s physical history, something she discussed with a friend while shopping for used records recently.

“We were just talking about how interesting it is that every vinyl you go to has a … history of how it got from being purchased to now being at this used record store,” Elser said.

In line with thrifting and recycling, collecting used records also reflects young people’s desire to live sustainably and connect to the past, Elser explained.

For Elser, the pandemic increased the desire for connection that records and antiques offer.

“Records are the oldest form of music communication we have, and there’s something so special about it.”

Greenberg said sometimes when younger people get into vinyl, they also get to dig into their parents’ or grandparents’ collections.

“So it’s a way of … connecting yourself to other generations, whether within your own family or an imagined community of other record listeners,” Greenberg said.

Kris McCormack, 24, started his record collection just a few years ago. “I knew that my dad collected them when he was younger, so I always thought they were neat.”

McCormack said his collection is a social thing. “When friends come over, they’re way more interested in it than I am.”

For McCormack, records make him feel more connected to the artists.

“You feel like you’re supporting them more than streaming,” he said. “For all of my favourite artists, I try to collect their whole discography that I can.”

McCormack said the hunt for specific albums also adds to the appeal. He said when he finds a rare record, “it’s pretty dope. … You feel like a true fan.”

The sensory experience of analog

According to Greenberg, young people are also shifting toward analog to consume something tangible.

“Young people generally grew up in an age of media ephemera, non-material media that exists on the cloud,” Greenberg said. “There is this longing of connection to materiality of media, and vinyl allows for that in ways that capture what you can hear, see, touch, taste and smell.”

McCormack also talked about the physicality of analog music as part of what makes it so compelling.

“It’s so crazy to me. Every time I use it, I’m like, this is a piece of plastic with a groove in it and a needle,” he said. “I just can’t wrap my head around how someone figured that out.”

For Boyd, the way analog music functions changes the music listening experience.

“When I put on a CD, it’s really easy for me to miss the whole thing,” he said. “When I put on a vinyl, I’m really engaged. There’s something that happens to my body that says, ‘I want to hear this.’

“Once you get analog, you kinda get hooked.”

According to Greenberg, part of that difference has to do with the way playing vinyl forces the listener to be intentional about how, when and where they listen.

“Each record becomes an extension of the person who owned them. It is entwined forever in their personal story and personal experience,” Greenberg said. “The record itself can be the medium that connects you to all these other people.”