By: Gwyneth Egan

Lisa Dai didn’t plan to go viral on TikTok when she got on the app to vent about her breakup. But millions of people have seen her come across their phone screens, posting content about the impact it had on her mental health.

The Australia-based content creator originally began posting random videos on TikTok back in 2021, including dancing videos, lockdown room tours and her manicure of the month. As time went on, she started making content on topics that became more prevalent in her life, like personal finances and mental health.

After a difficult breakup, Dai began posting about how she navigated her healing. In a video from July 19, she reflected on her progress five months later.

Dai’s TikTok posts about her breakup garnered thousands of views and hundreds of supportive comments from people across the globe who could relate to her situation. One comment read, “Digital arms around you.”

Although Dai is based in Sydney she has amassed followers from the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada.

“I just started posting because I wanted to vent,” she said. After reading the comments on her videos, she explained it felt “freeing in a way” because TikTok’s platform allowed her to speak openly about her experiences without worrying about the image she was putting forward.

Dai isn’t alone in sharing this content. Mental health is trending, and social media has changed the way people talk about it.

Trends on TikTok aren’t limited to any geographic region, so anyone anywhere can be part of the conversation, sharing their own stories, offering support, or providing advice to others. The platform has given people the opportunity to connect with a support system on a scale that’s otherwise inaccessible.

But, while apps like TikTok have made this possible, there are also dangers to the way information, whether true or not, spreads rapidly on the platform on a global scale.

The widespread access is a double-edged sword: while it has given rise to trends that have amplified and destigmatized the conversation about mental health, some experts say users should be cautious about seeking personalized advice on the internet.

#Healing in a digital world

“Before social media, and specifically before TikTok, people were pretty hesitant to bring up anything like anxiety, depression, certainly not trauma,” said Trey Tucker, a licensed mental health therapist and TikTok creator from Chattanooga, Tenn.

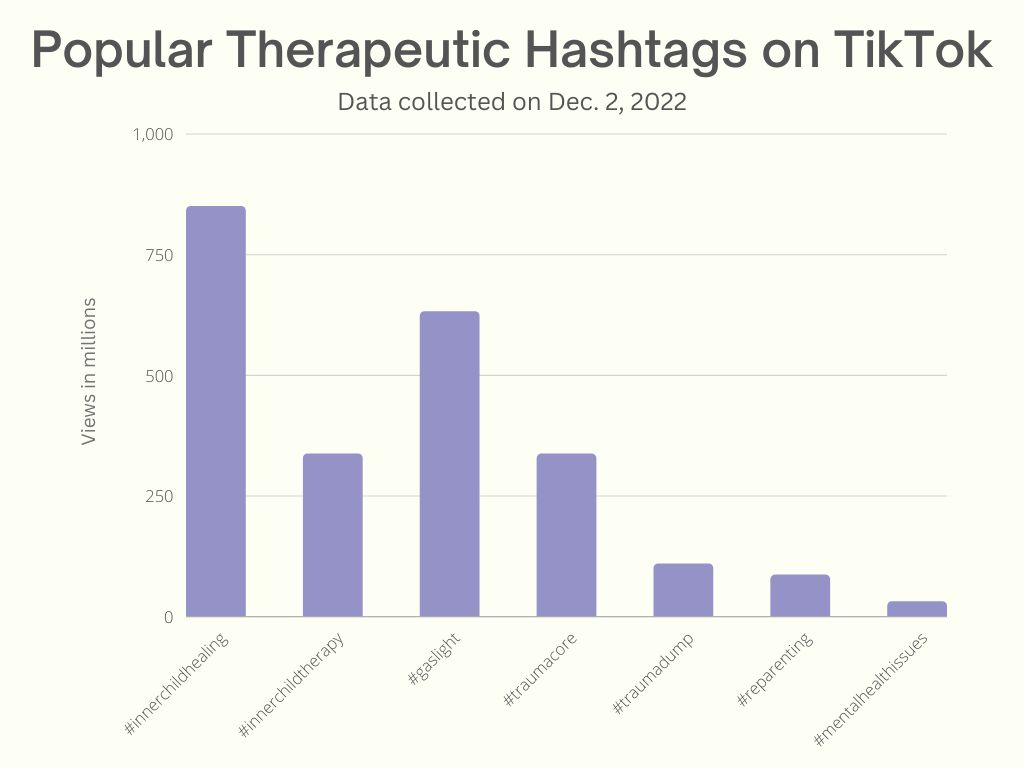

TikTok trends like the “heal your inner child” trend, where users try to connect with and heal their younger selves, have become increasingly popular on the app. The hashtag #innerchildhealing earned more than 850 million views at the time of publication, and variations of this tag have garnered millions more.

“Now, when someone sees somebody else on their phone getting vulnerable, talking about their experience, it really just gives the viewer some freedom to say, ‘Alright, well if this person’s talking about it then maybe it’s OK for me to talk about it, too’,” Tucker said.

The trendiness of mental health comes at a time when therapy and counselling services are not widely accessible.

The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health says wait times for access to services in Ontario can be long. Children and youth wait an average of 67 days for counselling and therapy and 92 days for intensive treatment in the province.

The Canadian Institute for Health Information says that before the pandemic, in 2019-2020, one in 10 Canadians waited more than four months for community mental health counselling.

Wait times are not the only barrier to access. Therapy can be expensive, and TikTok is both free and available at the touch of a button.

While long wait times and costs of mental health resources may not be directly associated with TikTok trends, the popularity and mainstreaming of therapeutic content raises the question of what impact TikTok has on mental health education.

‘User beware’

Trends on TikTok that normalize sensitive subjects are a part of what makes the app so appealing, but the content can be rife with misinformation. It presents major challenges for professionals who are trying to educate users about mental health and healing.

As both a mental health therapist and a TikTok creator, Tucker explained there is value in the app’s ability to “educate and then hopefully motivate somebody to just get curious about their own situation.”

On the other hand, TikTok videos are not the be-all and end-all of addressing mental or emotional vulnerabilities.

“In and of itself, this kind of content is not going to be a solution in the long run for you if you need serious help with how you’re feeling,” said Gavin Adamson, an associate journalism professor at Toronto Metropolitan University and expert in mental illness and media.

Adamson said that while some messages can be positive and helpful, “they’re not expert advice.”

“It’s kind of a user beware situation,” he said. The fact that anyone can get TikTok and post means that barriers to entry on TikTok are low, which Adamson said can be “positive on the one hand and dangerous on the other.”

Pooneh Montazeralsedgh, a registered psychotherapist based in Ottawa, said TikTok videos can be beneficial to those who don’t have access to other resources because it means “they are still using some form of videos or platform to learn more about mental health-related struggles.”

Stuck in the loop

Therapeutic terminology, like “healing your inner child,” has entered mainstream vocabulary on TikTok, along with other terms that were previously uncommon.

Montazeralsedgh said she doesn’t think the use of therapeutic language is a problem, so long as it’s used correctly.

“If it’s used incorrectly, it’s kind of spreading false information or giving people false hope about some of these terms and what they imply,” she said.

Tucker said he has seen this sort of misinformation spreading on TikTok with trends like inner child healing being diluted from its original therapeutic meaning. From video to video, as users interpret the trend in their own ways, the true meaning of inner child healing becomes miscommunicated.

While Tucker said that the idea of healing your inner child and addressing “internal injuries” is a genuine therapeutic approach, he added “the complicated thing is that the healing itself is probably not going to happen because of a TikTok video.”

TikTok trends that use therapeutic language may also exaggerate the potential outcomes of participating in such trends.

“It’s important to acknowledge what you’ve been through in the past, but on the other hand that doesn’t solve all problems,” Adamson said. He explained that the point of therapy and rehabilitation is getting out of “a loop” to better one’s own mental health, but social media algorithms are designed to keep you on the app, without “an opportunity to break out of it.”

“There is nothing besides the user that is going to intervene on negative content,” he said. “The algorithm is sort of insidious and it might drop some bit of a break for you, but before you know it, 10 minutes later, you’re seeing again the same sort of darker content.”

“Algorithms aren’t going to solve anybody’s anxieties or depressions,” Adamson said. However, Adamson said that for some “lucky” users, TikTok may be “a gateway to seeking treatment.”

Seeking solutions offline

For Tucker, mental illness can’t be solved with a quick fix like a short video on TikTok. He said the difficulty with addressing issues like healing your inner child is that “these parts of us usually didn’t form overnight and so they’re probably not going to go away overnight as well” and healing requires “self-compassion and patience.”

“We all want the hack or the cheat code,” he said. “But sadly, at least in mental health, there are just very few of those.”

Back in Australia, Dai is considering turning into a full-time content creator after the positive experience she’s had on TikTok. Even though she garnered popularity after her breakup, she’s hoping to find a new niche she can focus on for her content creation.

But the world of mental health content on TikTok is here to stay. Dai said she sees the increase in posts about mental health and vulnerability as a new normal.

As for Dai, she said she has been in a better place recently and isn’t posting as much about breakups or sadness. She said that although posting on TikTok made her feel good knowing that she was helping others, it “didn’t help me process my own feelings and thoughts any faster or better or more effectively.”

What did make a difference was talking to a psychologist, she said. “That was very, very helpful.”