CHAPTER 1

Rebels in the Empire“This school is different in that there are no bells to tell you when things start and stop,” says Sarah Sumner as she hurriedly pulls out drawers and rearranges desks. Her first class of the day is with the Grade 5 and 6 students, the oldest children that she teaches. And while Sumner has a master’s degree in mathematics from the University of Ottawa, arithmetic isn’t on today’s agenda at Académie de la Capitale, a private elementary school in Ottawa’s west end.

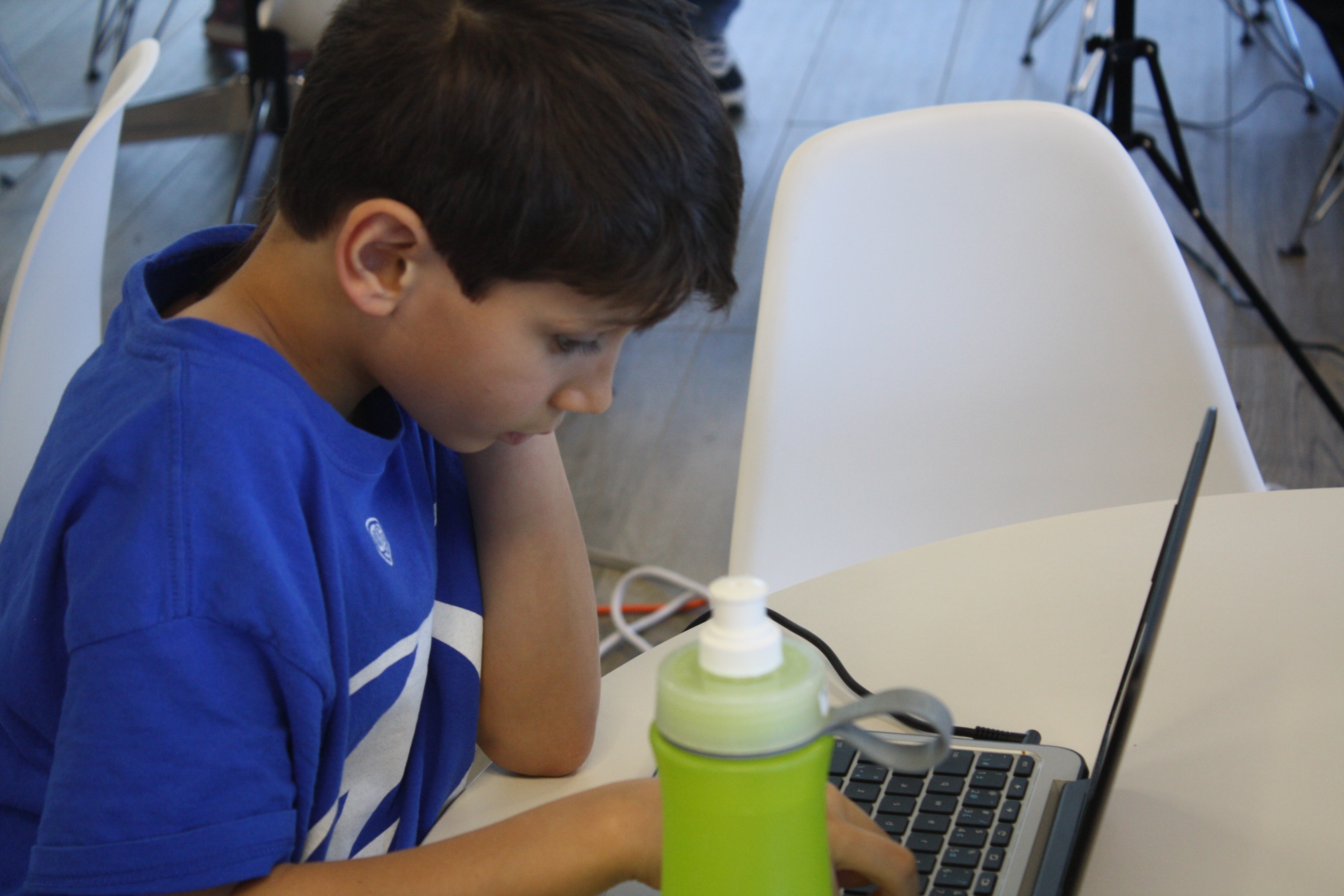

Indeed, pencils, pens and paper are notably absent. Instead, groups of two or three students each gather around a computer. Here, they use computer programming to animate characters and tell stories. Off to the side there’s a seemingly more traditional educational tool: a shoebox that houses a diorama. But there’s a twist: the diorama is hooked up to the computer, so the students are able to press buttons on their model that will control the characters on the screen.

In one corner, Grade 6 students Ethan, Sam and Ephraim have created a space station using Scratch, a program designed by MIT. Ethan speaks into the computer, recording a voiceover as an alien. “I’m from planet Pluto,” he cackles. After a passionate debate about whether or not Pluto is actually a planet, the group decides that the recording is sufficient.

Ethan, Sam and Ephraim, along with their colleagues, are learning the basics of computer coding twice a week, in their science, technology, engineering and mathematics unit. It’s an experience not available to public elementary school students in Ontario.

At its core, computer coding is the art of using a computer to adhere to commands. As multiple industries lean towards a more digital future, a premium has been put on the ability to use computers.

British Columbia recently released a three-year plan to institute the option to teach computer coding in schools for all children from kindergarten to Grade 12. Ontario has been hesitant to revamp the education curriculum despite the fact that it is home to one of the country’s largest tech sectors. In the 2011 census, the ‘professional, scientific and technical services’ industry was the fourth largest employer of people in Ottawa.

Currently, some, but not all, Ontario public schools offer computer studies electives for students in Grades 10 through 12. Though education is decided within provincial jurisdictions, federal studies have recently highlighted a few employment trends.

A study funded by the federal government’s Sectoral Initiatives Program in 2015 projected that provinces across the country will require an additional 182,000 ICT (information and communications talent) by 2019. In Ontario, the study predicted 76,300 ICT positions – the largest by far of the provinces – would need to be filled in the next five years.

For its part, the Ontario Ministry of Education says it is committed to computer technology education. “We are committed to continuing to work with our education partners and district school boards to promote effective practices for teaching and learning in a digital world,” says May Nazar, a public relations representative for the ministry. “That’s why we are investing $150 million over three years toward technology in our schools, including learning tools such as digital tablets, cameras, software, and extra training for teachers.”

Meanwhile, on a Saturday afternoon, across town from where Sumner holds court, a security guard rides an elevator up a Bank Street office building with a group of children. He’s bringing them to Steve Lavigne, a veteran computer programmer who runs a computer coding camp every weekend.

Lavigne started Kids & Code two years ago, when just three kids took the elevator ride up. The marketing efforts were more or less restricted to word of mouth and Lavigne’s Twitter account, but these days the free camps fill up on Eventbrite within a day.

Like Sumner, Lavigne starts up his camp goers in Scratch, and often moves them over to CoderDojo, a global program started in Ireland that makes it easy for beginners to learn code. Recently Lavigne and company started developing their own curriculum that is an amalgamation of the two, usually involving the end goal of a big project.

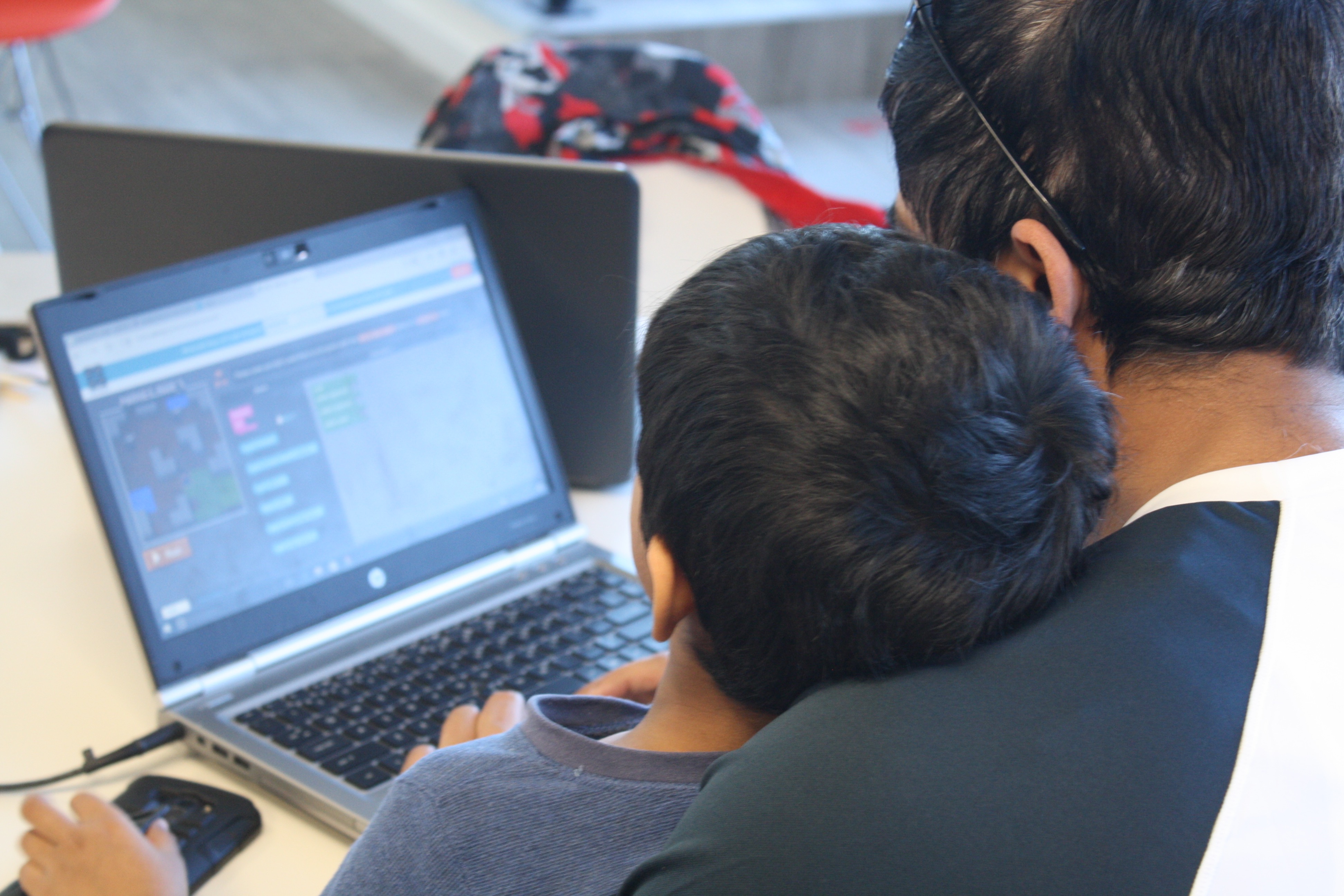

Lavigne and his crew of two or three wander around the crowd of children and their parents, supplying the former with cookies and juice boxes and the latter with coffee while helping out when they are needed. Parents of children under 12 must attend with their children not only because Lavigne, who is a father, “doesn’t want it to be like a babysitting situation,” but also because it’s easier for parents to help their kids when they go home.

“Most of the parents have no idea what they’re doing when it comes to code and stuff, but at least if they’re here and see it, they can grasp something more than a young child can, so at least they can kind of point them in the right direction.”

It’s clear that inroads are being made in Ontario towards coding, but how far that will extend is, right now, left to individuals.

Lavigne grew up and went to school in North Bay, about four hours northwest of Ottawa. When he applied to colleges in the area in 2001, most institutions offered computer-programming classes. He took a three-year diploma program in computer programming at Canadore College. The school has since cancelled the program. “I was like ‘that doesn’t make a whole lot of sense,’ and it was just from turnout,” recalls Lavigne.

“So I looked at my high school, where they used to have some coding clubs and things. It was small, just put on by the teachers, but they kind of slowed down and stopped on those things too, so then I started doing the research in the (United) States with code.org and the research they were doing.”

Lavigne says research found that people weren’t being exposed to computer programming in high school, and in most cases didn’t enrol in related programs in college. As a result, many of the college programs got cancelled. “And more of like, well, no one wants to be a computer programmer because even in grade school and high school, they don’t get exposure to it, then people aren’t signing up for it in college, the college isn’t getting enough money, so they cancel the programs.”

“So I thought ‘if that’s the chain, how is anyone going to learn anything? How is the federal government in Canada going to run all their mainframe systems if everyone who does it retires? Who’s going to do those things?’”

While the federal government’s most recent budget had a section entitled “Teaching Kids to Code,” it’s not known how the funds announced — $50 million over the next two school years — will be allotted.

While Finance Canada indicated that Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada would allocate the funds, the latter ministry did not give comment on the plans for that money.

As Ontario decides whether or not to dip its toe into developing a computer-coding curriculum, the province might look out west for lessons.