Chapter 5

For Whom does the Bell Toll?

When Finance Minister Bill Morneau announced the federal government’s commitment to coding in the 2017 budget, he did so by saying “we will encourage students to learn coding in the same way they learn to read and write, preparing our kids for the jobs of the future.”

What that looks like is still up for debate, with little to no indication from the government as to how the $50 million put aside for coding will be implemented.

It’s a battle that’s likely to continue to be waged on education boards and in provincial legislatures. No one wants to get left behind, and as the job market shifts rapidly and relies on new skills and technology, parents and teachers will be left fighting for their kids and their livelihoods, respectively.

Meanwhile, Sarah Sumner fights for both.

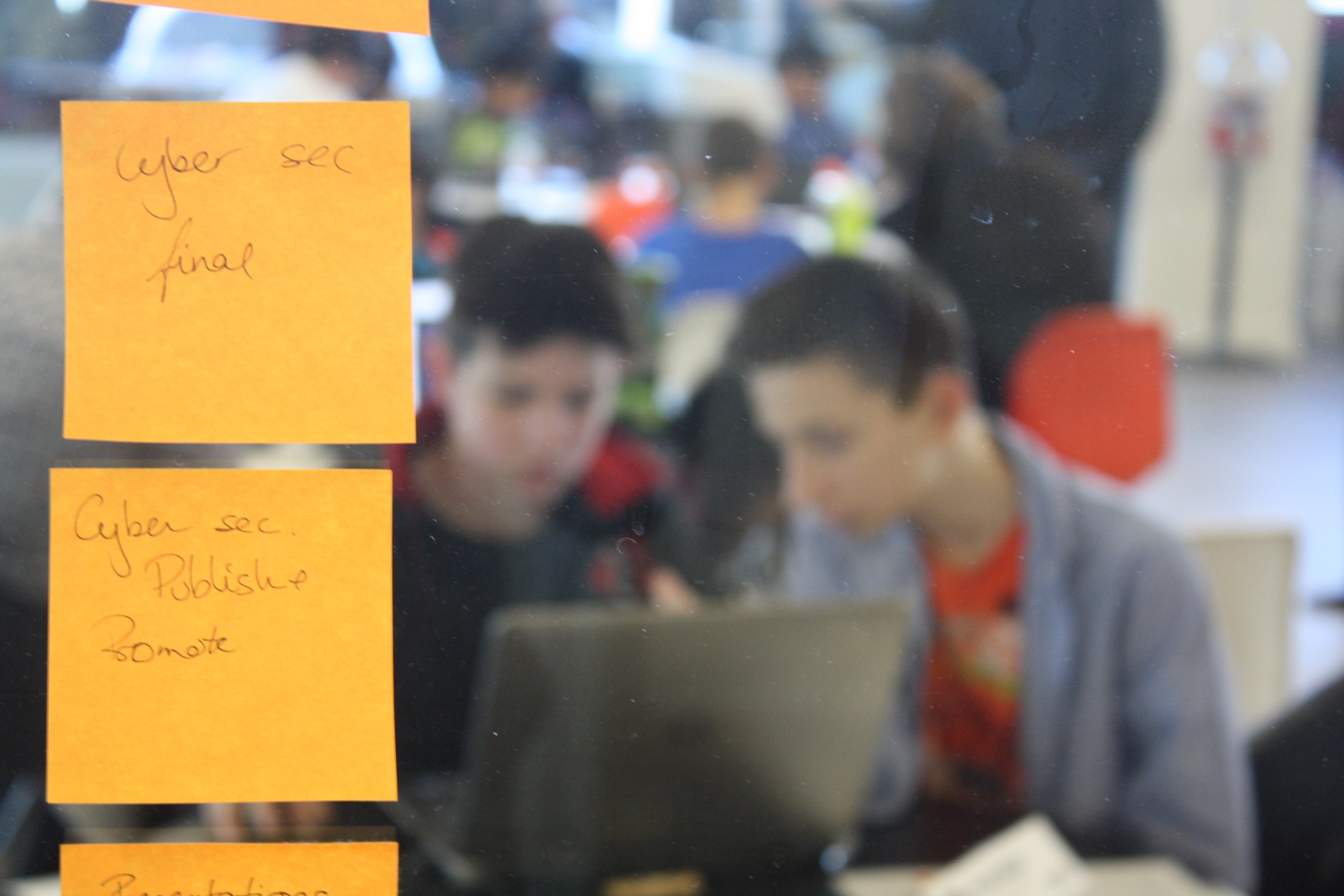

As the 11 students at Ottawa’s Académie de la Capitale run off to music class after a dizzying 45 minutes, Sumner packs away their computers. She is comfortable with the role she plays in computer coding education, both as a science, technology, engineering and mathematics teacher and as a parent. She has two young daughters who go to the school and she is meticulous in updating a blog that parents can access to see what their children learned each day.

“There are some students the program is a great fit for and there are others that choose to move on at times in their school career. There’s a lot of things the parents have to decide,” Sumner says. “My daughters started (working with computers) in daycare and just continued on. It’s a challenge but I think most of the time they like STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) too.”

For teachers like Sumner and Paul Doig, who teaches at B.C.’s Shawnigan Lake School, private education seems to offer both the freedom and resources to teach coding.

“I think there’s some necessarily back-end stuff that needs to be done to help a full-scale adoption of computer programming in schools,” says Doig, referring to the lack of computer science experts in most schools across the country. Even at Shawnigan Lake, which boasts an abundance of computers and where almost every student has a laptop, Doig is one of only two teachers with an aptitude in computer programming.

“Just think if we never had a biologist in the school, how are you going to get biology into the school? It’s a challenge that’s going to happen but it’ll happen and some of the faculty members that I know are keen to learn it, but they also have to be trained. Computer science is logical, but it’s not always intuitive, if you know what I mean.”

It remains to be seen whether public schools will be able to catch up, even if provided the federal funding. It’s also unknown if coding will ever become universal or prevalent. So far, it looks as if B.C. is falling far short of its goal to have, in the words of the premier, “every child speak code.”

Rita Agarwal, who, like Sumner, starts young students out with the MIT-developed program Scratch, thinks that coding can be brought into schools in a cost-effective way.

“For beginners, you don’t need to have experts. You can have three hours of training at that level, maybe two days of training and start with some group projects.” Scratch is a simple program, she insists, and doesn’t take very long to master. It’s also an effective building block that can be used to learn other programs.

“The concepts are pretty closely tied to actual programming, you can make loops, you can make conditional statements, like ‘IF_____, THEN ______’, so it’s the exact same structure. Once they get the logic, once they get the structure, it’s easy for them to transfer to actual programming. But still, in between, if you talk about Java or Python, or anything that needs typing, you do need certain typing skills, and you can get frustrated. Kids learn at such different speeds. But before they know it, the teachers will have their own students helping them.”

She speaks from experience in that she uses older students as teaching assistants. “The kids that help me, some of them are 12 years old. I pay them a little bit and they get the kids working on new projects and skills.”

With people like Sumner and Steve Lavigne trying to ensure that children in Ontario get some exposure to computer programming and pushing the envelope forward, it seems inevitable that the curriculum will be in public schools in the near future.

“It’s fun,” says Ethan, a sixth grader in Sarah Sumner’s class, as he controls an alien on his screen. He uses a microphone to record his voice and programs the alien to move his mouth simultaneously.

“I’m from Planet Pluto,” he says. And, for some reason, you believe him.