The six tornadoes that ripped through the Ottawa region in September forced thousands of people to find help getting food. The unanticipated surge in demand raided the pantries of the already strained Ottawa Food Bank. Now, there’s a danger that people who regularly rely on the food bank’s support will feel the effects of the storms too.

The twisters knocked out power to 11 community food banks in Ottawa, leaving a lot of food to thaw and spoil in the warming fridges and freezers even as demand burgeoned. In a City Hall meeting Thursday, Michael Maidment, CEO of the Ottawa Food Bank, expressed his concern with the food banks ability to keep up. The tornadoes left Ottawa’s food security network in a whirlwind of trouble.

Maidment worries that as time passes donors may forget about the crisis and think of their one-time donation after the tornadoes “as an ‘advance’ on their Christmas giving,” resulting in a shortage during and after the winter season.

When food banks have a shortage of food, many people may suffer. Samantha Anderson, a 21-year-old student, uses the Carleton Food Center throughout the year.

“Sometimes I just can’t afford real food since it’s so expensive,” she says. “I don’t have much help in Ottawa. I don’t know what I’d do without [it].”

Anderson is part of an increasing number of people in Ottawa growing hungry and more helpless because of the rising cost of living and low wages. She tries to save where she can. “I had to move out of the Glebe and further from school to save on rent.” She says, “that helped a little.”

Anderson hasn’t had trouble in the past securing meals from the food banks in the winter time. It is prime season for the services too. Maidment says that his organization brings in over half of their annual revenue in the winter when people need help the most.

GROWING DEMAND

Though food banks prepare for a surge in winter demand, trends show that usage is climbing all year round, up 5.6 per cent since 2016, according to the Ottawa Food Bank hunger report. Maidment believes that the surge is a symptom of a more significant problem—inadequate wages and social assistance rates in relation to the rising cost of food and housing in Ottawa.

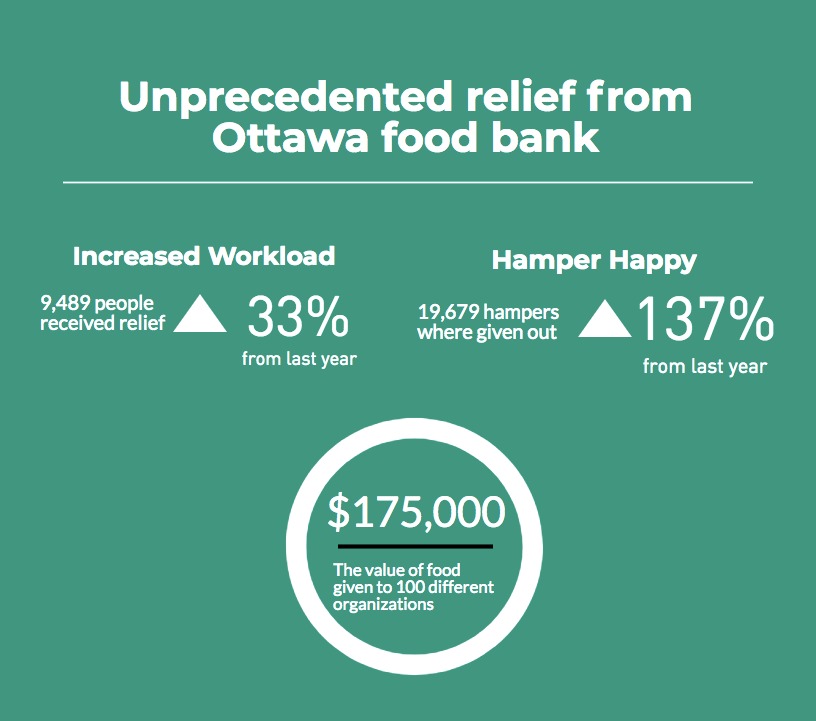

With that in mind, the Ottawa Food Bank recognized a need to step up and help with the tornado relief effort. Since the tornadoes landed, it has delivered over 19,000 hampers and reached more than 9,000 people.

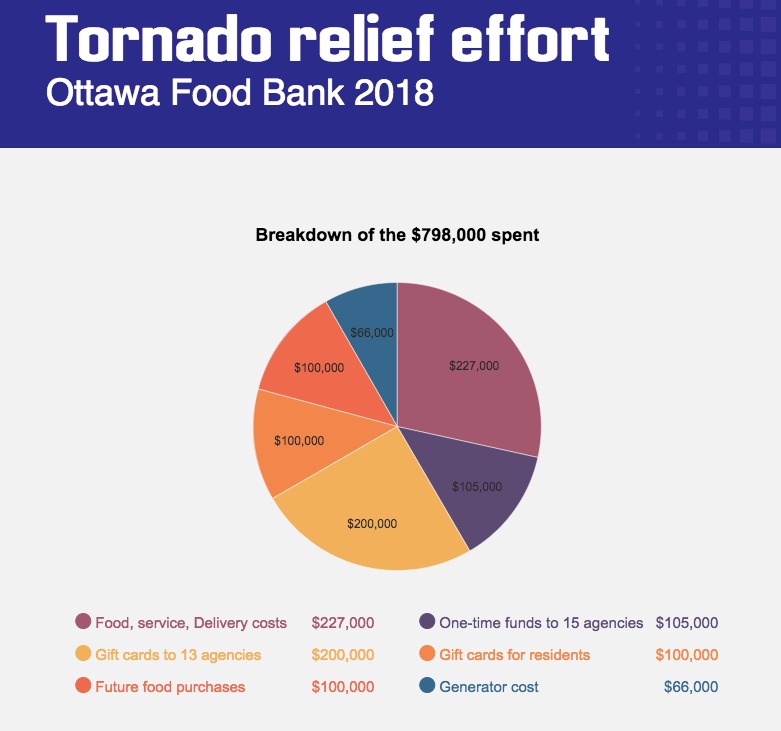

The quick response, according to Maidment, was a result of solid preparation by the Ottawa Food Bank to keep a six-month reserve of non-perishable food items on hand at all times. Between their reserve and donations, they spent $798,000 on the entire tornado relief effort.

The food bank is an emergency service that is built for these sort of crises, according to Maidment. “Every month we provide support to 38,400 people, so whether it is a tornado or a family that doesn’t have enough income to put food on their table, both are emergencies and look pretty similar.”

The power outages at 11 food banks, however, were not in the crisis plan. A lack of power made any relief efforts much harder to deliver since community food banks and residents had no way to store or cook their food.

This proved to be a learning experience for the food bank. The organization has since bought a generator for their warehouse and is looking to get more refrigerated vehicles for their mobile fleet.

INSECURITY IN OTTAWA

One in 15 households in Ottawa report being moderate to severely food insecure and the cost of following Canada’s food guide has risen 18.6 per cent since 2009. Furthermore, 59 per cent of all food bank users rely on some form of social assistance, says Maidment.

For Anderson, rising prices mean sacrificing healthy eating.“Maybe if rent or food was cheaper I could afford fruit, but it’s hard as a student,” she says.

In order to aim for a balanced diet, Anderson takes advantage of the Ottawa Food Box program, which allows her to buy fresh produce once a month at a reduced cost. The program is a initiative out of the Centretown Community Center. They deliver the boxes to 40 neighbourhood food bank locations where people like Anderson can pick them up.

SOLUTIONS TO THE PROBLEM

Bridget King, a food security advocate from Sustain Ontario, recognizes Anderson’s struggles, but she says that food banks aren’t the perfect fix. “Poverty is the root cause of food insecurity,” she says. “If people don’t have the money to afford food, then [food banks become] a band-aid solution.”

Instead, she wants government to address the root causes of poverty by increasing social assistance or introducing basic income guarantees. That way, King says, aid will root out the problem and not just the symptoms.

King’s suggestions come at a time when the Ontario government is re-evaluating the current Ontario Works and Ontario Disability Support Program. The 100-day review ended Nov. 11, with what the Progressive Conservative government calls evidence-based results and plans being announced on Nov. 22.

“The previous government’s solution aimlessly threw money at the problem without any plan to help people get out of poverty,” said Community Services Minister Lisa MacLeod in a statement released on Wednesday, Nov. 7. The statement goes on to say that “the best social program is a job.”

“Income is the main barrier and cause of food insecurity,” says King. “We strongly encourage the provincial government to rethink their plan of winding down the basic income project.” The plan was implemented by the previous premier, Kathleen Wynne.

MacLeod could not be reached for comment.

Until policies are made and actions happen, people like Anderson will still struggle to fill their fridge with healthy options. She will continue to rely upon the food bank while making adjustments to her personal budget. But she can only do so much, and has been left to wonder when concrete change will weather the storm.