The business of e-cigarettes

One of the biggest debates in regulating e-cigarettes is deciding whether they are a medical device or commercial product.

Lead researcher from the Propel Centre for Population Health, Christine Czoli, explained if the product were considered a smoking cessation alternative it would be regulated as a medical product.

If e-cigarettes were medically regulated they would be able to be officially prescribed by a doctor. However, they would also need to undergo strict testing and conform to a standard set by Health Canada. Only Health Canada-approved e-cigarettes and e-liquids would be available and only in pharmacies or at natural health product retail stores.

While some doctors currently recommend e-cigarettes to patients to help them quit smoking, they cannot officially prescribe it. Adding to that, nicotine-containing e-cigarettes are currently illegal in Canada.

Regulating e-cigarettes as a health product would allow doctors to prescribe e-cigarettes as a smoking cessation aid. Regulating e-cigarettes as a commercial product would allow for greater accessibility and product placement.

Specifically, it would allow e-cigarettes to be sold beside tobacco cigarettes, which could give the user an option to choose his or her preferred product.

Currently, almost all provinces and territories have legislated that tobacco cigarettes be hidden behind the counter in grocery and corner stores.

In 2009, the United States Food and Drug Administration lobbied to have e-cigarettes regulated as a drug. It was a debate that would ultimately end up in court, with judges ruling that e-cigarettes should not be regulated as a drug but instead as a tobacco product. Canada lacks any such clarity.

E-cigarettes should be regulated neither as a consumer product nor a health product, according to tobacco harm reduction expert, David Sweanor.

“It’s sort of like asking someone to sort shapes into circles and squares, and then you get a triangle and they say now what should I do with this?” says Sweanor.

Current e-cigarette market

It is important to consider the stakeholders in this situation. Who will be affected by e-cigarette regulation, and how will it affect them?

There are certainly two industries which will be affected by e-cigarette regulation: pharmaceutical companies which are marketing smoking cessation products, and tobacco companies.

Despite a lack of regulation, the e-cigarette market has been growing extremely quickly.

According to Euromonitor, a UK-based market research firm, global e-cigarette sales hit US $6 billion in 2014. In June 2015, Euromonitor estimated that the global e-cigarette market would reach $23 billion by 2019.

US-based marketing research company BIS Research echoed that sentiment, forecasting annual market growth of more than 22 percent per cent from 2015 to 2025. At that rate, the market would reach $50 billion by 2025.

Today, analysts are less bullish on the e-cigarette market. A recent article in the Wall Street Journal highlighted concerns that the once-rapid growth may be slowing down.

Adding to this is a Bloomberg article showing a steady decline in recent e-cigarette sales, with sales falling each month from December 2015 to February 2016.

Still, pharmaceutical companies and tobacco companies are battling over e-cigarette regulation.

Big Pharma

Gopal Bhatnagar says he was ready to face animosity from the tobacco community. What he was unprepared for was the pushback from large pharmaceutical companies and researchers funded by other tobacco cessation initiatives.

E-cigarettes have been a disruptive technology for pharmaceutical companies involved in the nicotine replacement therapy market.

Pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline—which make nicotine replacement therapies including Nicorette, NicoDerm and Zyban—lobbied the European Union against electronic cigarettes. Information from a previously released access to information report showed that the company asked for the products to be regulated to the same extent as its nicotine replacement products.

Beyond that, there is also a movement to create a negative public perception of e-cigarettes. For example, Nicorette has put out advertisements trying to discourage users from switching to electronic cigarettes.

Even if e-cigarettes were regulated as a medical product, they would still be available as an alternative to other smoking cessation tools, so what do pharmaceutical companies stand to gain in this debate?

If e-cigarettes are not regulated as a medical device, then their makers cannot make any claims about being a smoking cessation tool. But this does not seem to be hurting the perception that e-cigarettes can help people quit smoking.

In the UK, where e-cigarettes cannot be marketed as smoking cessation devices, a University College London study showed that nearly one-third of smokers trying to quit were doing so by using e-cigarettes.

Pharmaceutical companies now fear that e-cigarettes are perceived as a smoking cessation device while being regulated as a commercial product. This gives e-cigarettes the advantage of being readily available while also attracting users who are looking to quit smoking.

Big tobacco

In 2013, ten years after e-cigarette inventor Hon Lik sold his product to Dragonite, tobacco giant Imperial Tobacco bought Dragonite’s e-cigarette branch, raising questions about the unholy alliance between a company that reaps the benefits of toxic cigarettes and a product that was promoted as a device to help people quit smoking.

“Despite my dislike for how tobacco companies have maliciously acted in the past, if they eliminated combustible tobacco and they sold only electronic vaping products and there was no combustible tobacco in society… that would still get us our tobacco harm reduction end-point,” says Bhatnagar.

Imperial Tobacco is not the only tobacco company to have hopped on the vaping bandwagon. Currently, tobacco giants Altria, Reynolds America and Japan Tobacco all have their own lines of e-cigarettes.

Big tobacco companies clearly have a hand in electronic cigarettes. But the $6 billion in global e-cigarette sales in 2014 pales in comparison to the more than $700 billion in global tobacco cigarette sales.

So if e-cigarettes are such a small portion of the market, why should tobacco companies be concerned?

The most obvious answer is money. The electronic cigarette industry is growing, and if the growth continues electronic cigarette manufacturers will reap the benefits.

For health products, the onus is on the manufacturer to meet regulations. This means e-liquid producers would have to test all of their products in a lab, a costly and time-consuming process. In the United States, it was estimated that the approval process estimated that this process would cost e-liquid producers millions of dollars.

Another main benefit of being regulated as a tobacco product rather than a medical device is consumer availability. Tobacco products are available in all sorts of retail stores, while smoking cessation tools are only available in pharmacies or at natural health product retail stores, which is why e-cigarette manufacturers would like to see e-cigarettes regulated as tobacco products.

But there may be a second, more ominous, reason why tobacco companies are interested in e-cigarette regulations. While the debate so far has revolved around e-cigarettes and their potential to help cigarette smokers quit smoking, there are concerns electronic cigarettes may also have the opposite effect.

As e-cigarettes grow in popularity and become socially acceptable, they could be acting as a kind of gateway to attract non-smokers into eventually smoking cigarettes. A 2015 study by the University of Pittsburgh, funded by the National Cancer Institute, suggested that adolescents and young adults who smoke electronic cigarettes are more likely to end up smoking tobacco cigarettes.

A 2015 Center for Disease Control and Prevention study found that nearly 10 per cent of those aged 18-24 had tried an e-cigarette but had never smoked a cigarette, increasing fears that e-cigarettes may be attracting non-smokers.

“Ideally e-cigarettes should be marketed to adult smokers. That is where their health potential lies,” says Czoli.

Youth

If you walk into a vape shop, almost everyone there will share a story about how the switch to vaping from tobacco smoking changed his or her life.

Ty Greer’s life has definitely changed—but not positively.

The 16-year-old from Lethbridge, Alberta was smoking an electronic cigarette when it reportedly exploded approximately two inches from his face. The explosion left the teen with extreme third degree burns on his face.

Greer purchased his Phantom Wotofo e-cigarette at a vape shop in Lethbridge.

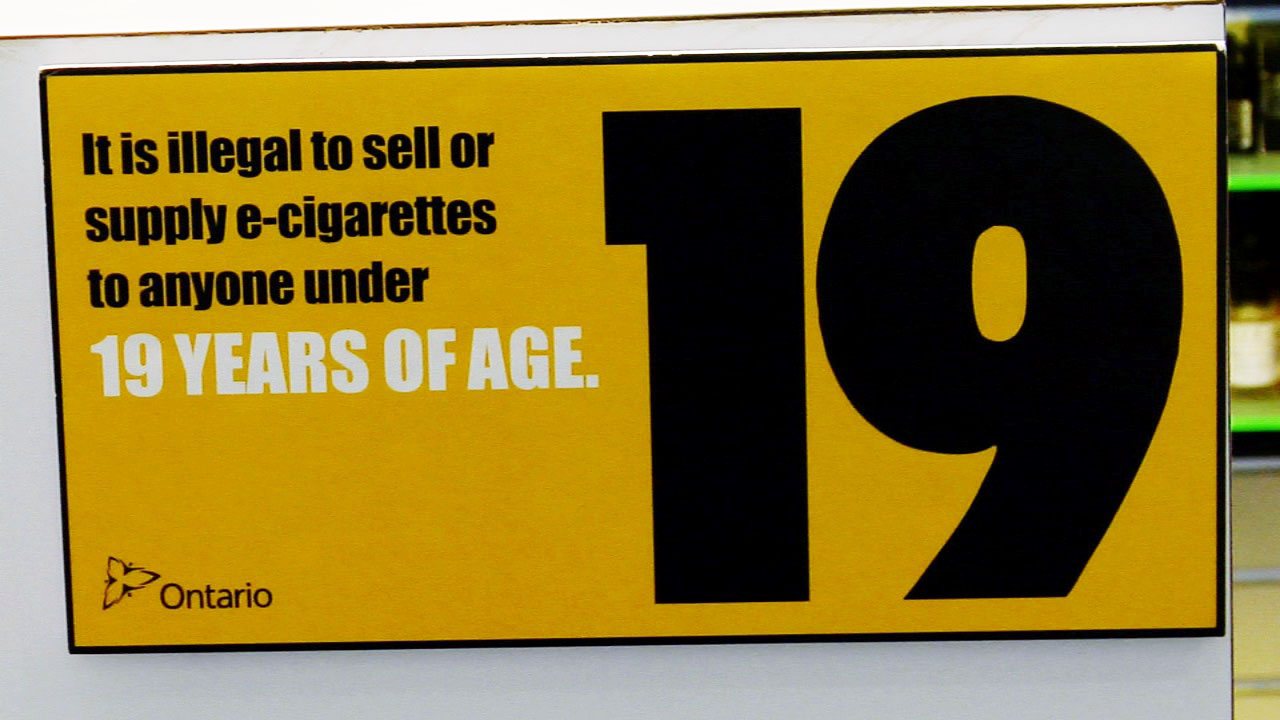

Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, Quebec, and British Columbia ban the sale of electronic cigarettes to minors—Alberta has no such ban.

After Greer’s accident, Alberta called for more stringent regulation on selling electronic cigarettes to minors, but to date no legislative action has come of this.

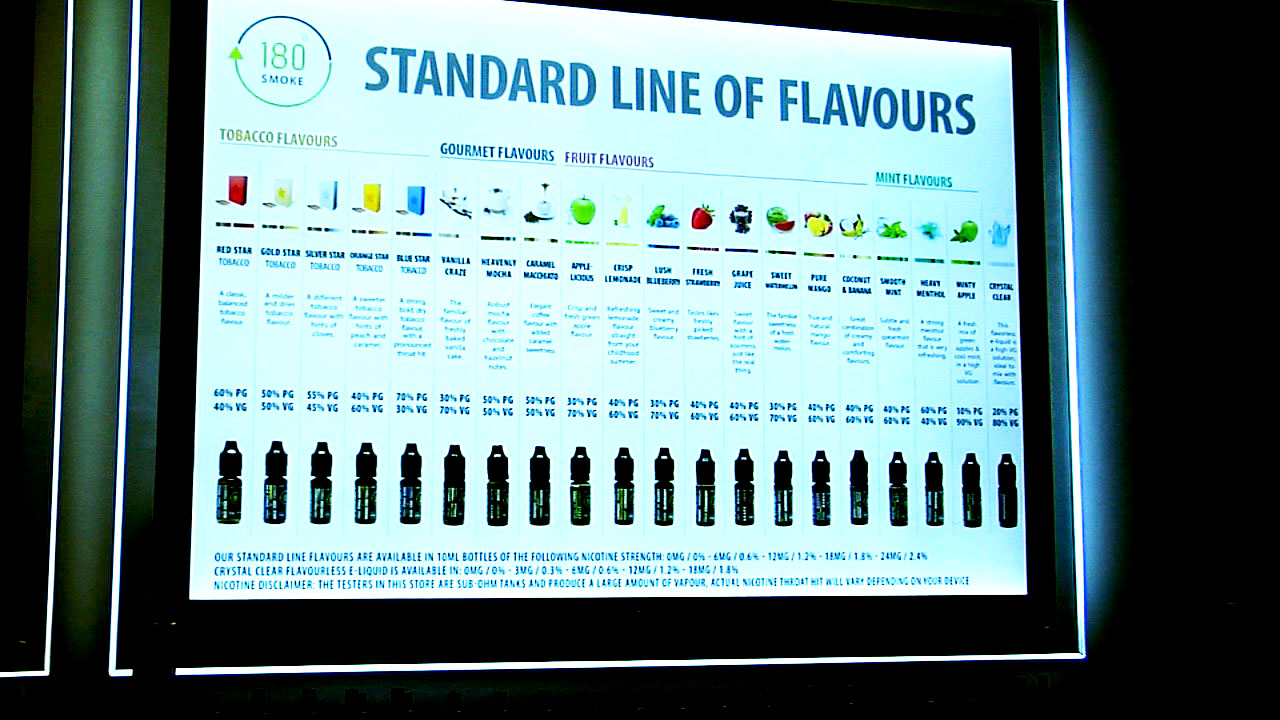

More than 7,700 e-juice flavours exist today, according to a study from the University of California San Diego.

“I could probably list a few and make them up and honestly they’d probably be real,” says Czoli. “Flavours that are most talked about are things like cotton candy, pina colada, fruit flavours etc.”

180Smoke salesperson Keith Hucher says most of his clients ask for the fruity flavours.

What concerned Czoli and other researchers is that these flavours could potentially be attractive to young people. The fear is that the e-cigarette industry may target youth in the same way that the tobacco industry did and arguably still does.

A 1999 study by the University of British Columbia examined documents released by tobacco companies Imperial Tobacco and RJ Reynolds in a 1987 lawsuit. The analysis showed that these companies targeted two main segments of the population: people who were considering quitting smoking, and youth who had yet to begin smoking.

Today, e-cigarette marketing techniques can target youth with flavours, packaging and colours. E-cigarette flavours vary from bubble gum to tobacco, the packaging comes in different sizes and colours, as do the actual e-cigarettes.

In Canada, e-cigarettes are seemingly more attractive to youth than to adult smokers. According to the Propel Centre study, a person’s likelihood of ever using electronic cigarettes was largely shaped by two main factors: the person’s smoking status before trying the e-cigarette and the person’s age.

The Propel Centre report suggests e-cigarette consumption to be most prevalent among young adults between the ages of 20 to 24, with 24.5 per cent having ever used one. This was followed the 15 to 19 year-old age category, at 19.8 per cent.

Some advocacy groups fear e-cigarettes are more likely to be a gateway drug that would ultimately encourage youth to shift from e-cigarettes to standard tobacco cigarettes. They also fear that electronic cigarettes could renormalize smoking.

“Action must be taken before these devices become a more established public health hazard. Policies to de-normalize tobacco smoking in society and historic reductions in tobacco consumption may be undermined by this new ‘gateway’ product to nicotine dependency,” wrote Richard Stanwick, a former president of the Canadian Pediatric Society, in a position statement.

Kate Ackerman, spokesperson for the Electronic Cigarette Trade Association of Canada (ECTA) says most vape shops want restrictions on selling e-cigarettes to minors, but says the argument that electronic cigarettes would lead to tobacco smoking or renormalize smoking is unsubstantiated by research.

Ackerman says vape shop members of ECTA agreed not to sell to minors so as not to encourage addiction to nicotine among youth. Bhatnagar says most shops acted in good faith and didn’t sell to minors prior to regulations being enacted.

He contrasted this with tobacco companies.

“Tobacco is a growing industry around the world… they’ve got 4 year-olds addicted to chain smoking in Indonesia,” says Bhatnagar.

But will children become attracted to e-cigarettes and what are the moral implications if that happens?

Statistics Canada found that the younger a person is when they start smoking, the more difficult it was for them to stop smoking. Also, most youth and young adults who tried vaping are actually ex-smokers. So, while it definitely should not be encouraged, transitioning to electronic cigarettes may not be a bad thing for all youth.

Labelling

Another marketing concern is how e-liquid is labelled. Some e-juices don’t have a label on them—while other companies simply lie about the ingredients.

“Buddy down the street could be making it in his bathtub,” says Hucher.

Some vape shops are more diligent than others, but everyone interviewed for this project agreed that the industry was lacking regulation and consistent standard practices that would allow for better packaging and labelling of products.