THE COMPOSING

/kəmˈpōz/: 1. write or create (a work of art, especially music or poetry); 2. (of elements) constitute or make up (a whole)“I would describe it kind of how everybody eats in Toronto,” says Jordon Manswell. “I don’t really know anybody that just eats ackee and saltfish or just eats jerk chicken and rice. You can go down the street and eat Ethiopian food, you can go eat Thai food, you can go eat a bunch of different flavours because that’s just how Toronto is.”

For Manswell, the diversity of Toronto has created a “melting pot” of different cultures and different talents in the black community — all to the benefit of music in the city.

“Black Toronto music has infusions of almost every single culture there is,” he says. “I feel like we’re so creative that we’re able to mix all of these things in seamlessly and it’s not so obvious, but it’s still authentic to who we are.”

The authenticity behind the sound is something that was developed over time with the growth of black communities in the city.

Canada is home to almost 750,000 Caribbeans and over one million Africans, according to Statistic Canada’s 2016 census. More than half of Caribbeans — over 460,000 people — live in Ontario and of that, more than 165,000 people reside in Toronto. The largest group from the region is from Jamaica.

People of African origin in Ontario number more than 414,000, with more than 146,000 living in Toronto. Most originate from countries in Southern and Eastern Africa with the largest group in Toronto being those of Somali origin.

But prior to the 1960s, immigration of black people from African and Caribbean nations was low. The Immigration Act implemented in 1910 gave the government more discretionary power to regulate the flow of immigrants into the country. The act stated that the governor-in-council had the right to bar entry into the country of “immigrants of any race deemed unsuited to the climate or requirements of Canada.” The following decades saw little growth in the black population in Canada while the discriminatory legislation was in place.

Dealing with a post-war need for domestic labour in the 1950s, the federal government established the West Indian Domestic Scheme. It granted black women from the Caribbean between the ages of 18 and 35 the opportunity to obtain immigrant status in exchange for a year of service as domestic workers. Canada admitted more than 2,600 women to the country through the scheme.

While it did play a part in growing the black presence in Toronto, there was already a black community in the city almost a century and a half before the program began.

Of the black people who did make the journey to Toronto in the early nineteenth century, several settled in the St. John’s Ward neighborhood that was centered around Bay Street and Albert Street, today the site of Toronto city hall. They began to open businesses, while others built a community to the northwest in what was known as the City of York (south of North York and between Etobicoke and Old Toronto) before it was amalgamated with five other municipalities to create today’s Toronto.

It wasn’t until 1967 when the federal government under Lester Pearson dropped the racially discriminatory legislation and black immigration began to rise dramatically.

Now, neighborhoods like Jane and Finch, Rexdale and Weston are more frequently associated with black Canadians (although they are ethnically diverse) and have since become places where large black populations from countries like Jamaica, Somalia and Ethiopia have made their homes.

Genres of music, like R&B and soul (that were originally pioneered by African Americans from the 1940s to the 1960s) had a home in Toronto, bolstered by interest in the music from the United States.

Radio show host Charles ‘Spider’ Jones was there to see the genres take root.

As a young man, Jones made a name for himself in amateur boxing and was a three-time Golden Glove Champion. He was also inducted into the Canadian Boxing Hall of Fame in 1996.

He spent some of his younger years in Detroit where he learned to appreciate the sounds of that city, especially that of Motown Records. It left him with musical tastes that aren’t exactly lined up with that of the “white-bread” Toronto that prefers rock. He mentioned the Barenaked Ladies, a Scarborough rock band, as an example of music he doesn’t care for.

“I can’t get into that stuff,” he says. “When you grew up on The Temptations and The Spinners and Teddy Pendergrass, it’s very difficult to settle for less.”

He says music is a balm, an “opium” for him.

“I became sort of historian, researching it, because of my love for music. When I want to get relaxed I put on my music, whether it be jazz, R&B, pop, southern rock or whatever.”

It was this passion that lead him to a career in radio that lasted 25 years.

His show — aptly named The Spider’s Web — started in 1988 on CHWO, a small radio station out of Oakville, Ont. Jones played the hits of R&B and blue-eyed soul from the mid-1950s to 1975. A bit of an incongruence, since the population of Oakville is largely white, with more than 123,000 of the total 193,000 residents being of European origin, according to the 2016 census.

The Spider’s Web allowed him to interview the greats in soul like Smokey Robinson and Curtis Mayfield.

“I played what people asked me to play but it was basically geared around soul music,” Jones says. “I like to think I did my part to keep it alive in Toronto.”

“When you’re talking music, you’re talking with Spider Jones.”

He says that when he arrived in Toronto in the 60s “Toronto was the blue-eyed soul capital of the world.”

There wasn’t much in the way of Canadian soul but on his show, Jones featured acts like Crack of Dawn, a Toronto R&B, funk and soul group. The group is known for being Canada’s first black band signed to a major record company, Columbia Records. They were originally formed in Kingston, Jamaica, but moved to Toronto in the mid-70s and went onto release their self-titled debut album. Singles like It’s Alright (This Feeling) and Keep the Faith helped solidify their place in funk in Canada. Both songs have elements of classic funk, with a driving, deep bass line that helps ground the rhythmic groove.

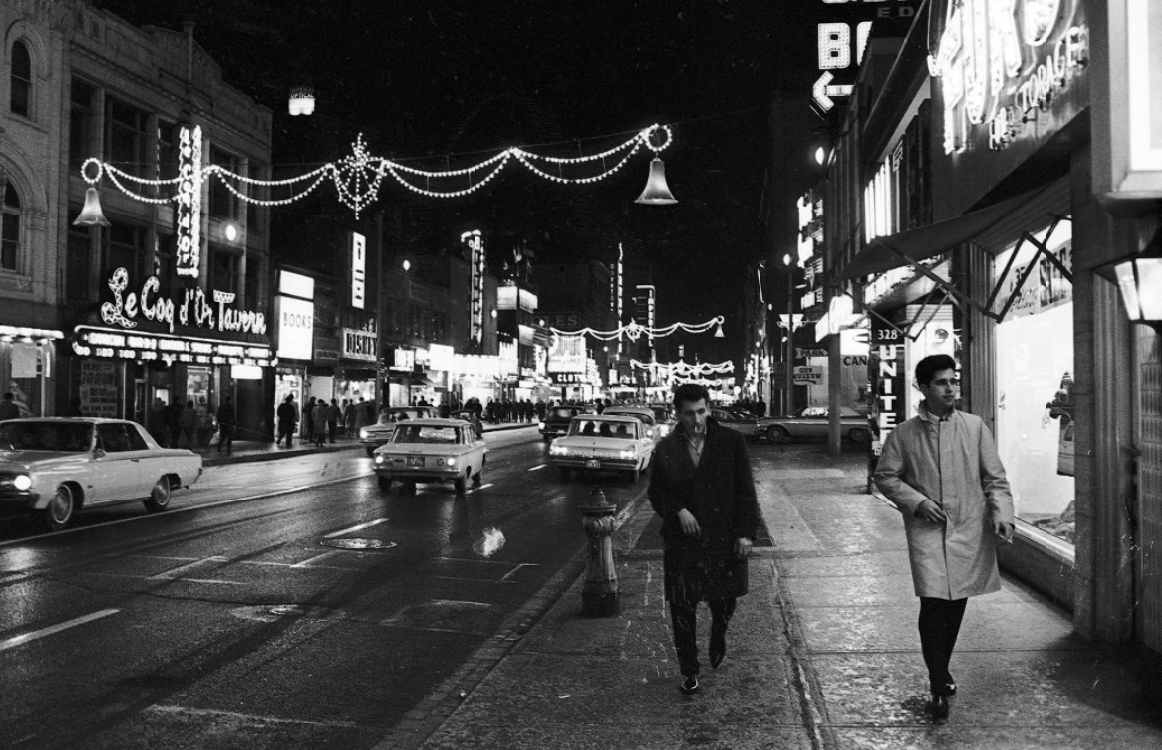

The genres flourished in certain hubs in the city. Jones spoke of places were black musicians, from both Canada and the U.S., gathered to play in front of huge nightly crowds. He mentioned Le Coq D’or Tavern, a pub located in the heart of the city on Yonge Street.

Jones says the Tavern was run by Ronnie Hawkins who was himself a part of a rock group called Ronnie and the Hawks. The group toured around the southern U.S. before Hawkins came to Canada when rock was beginning to gain traction and ended up at a gig playing at Le Coq D’or. Hawkins would go onto bring in black talent into the club, says Jones.

There was also the Sapphire Tavern where Jackie Shane frequently played.

Shane was American, born in Nashville, Tennessee, but made her career on Yonge Street as a pioneering transgender performer. She died earlier this year in her hometown.

Her hit single, Any Other Way, was classically 60s R&B with a supporting piano and blaring brass section.

Shane and other artists helped create what was Toronto’s sound at the time.

“Toronto was really into that soul thing in the 60s,” Jones says “The rock thing wasn’t big at all. Yonge Street and along it was all soul music.”

It wasn’t until the 70s when migration from the Caribbean started to accelerate that Toronto began to see other black genres begin to get a foothold.

Hip hop is a broad term (it was at one point the definition of an entire subculture that has now become much more mainstream) that can describe anything from clothing to vernacular. But the music is characterized most often by a rhythmic foundation of syncopated drums and lyrical gymnastics that come from a tradition of performance poetry.

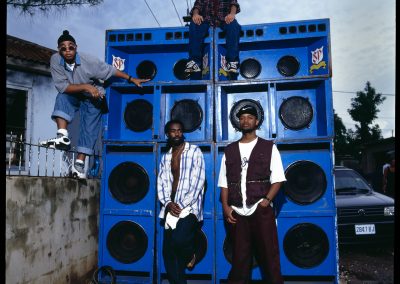

Though hip hop in Canada did draw from its American counterpart, in Toronto it took on aspects of different cultural identities.

“In the late 90s, the sound was still very much ‘boom-bap’ but there was a lot of heavy Caribbean influences, like Ghetto Concept,” says Mark Campbell. “They weren’t necessarily Caribbean but you could hear it in the production.”

Ghetto Concept was a hip-hop duo composed of Kwajo Cinqo (Kwajo Boateng) and Dolo (Lowell Frazer) of Toronto. The pair was later joined by Infinite (Desmond Francis) who left the group in 1995.

The instrumentation on their hit single E-Z on Tha Motion is quite jazzy but on his verse, Kwajo Cinqo slips into a patois accent while he boasts about “flexing” on his contemporaries:

Styles are too complex, so ooh—you betta just

Balk and ease! You are beginning to get me vexed

No matter what, you c’yah stop the flex when it wrecks

The Caribbean influence is highly observable in the music of Canadian rapper Kardinal Offishall. Kardinal, originally Jason D. Harrow, was born in Canada and raised in Scarborough by Jamaican parents. He came up in the hip hop world in Toronto in the 90s and is known for the reggae and dancehall vibe he brought to his music. He’s now considered one of Canada’s largest international hip hop stars.

In his single Ol’ Time Killin’, Kardinal flowed between a typical Canadian accent and a Jamaican patois:

When dem man dem murder song before a dance

Can’t turn around and jump and begging for a bligh

Lick off a style, me-a-fi put dem all back

Rap from T-dot to the Bronx and Brixton and come back

On the production side, the song definitely showcases aspects of Jamaican music.

“All you hear besides the fog horns, which are very much from Jamaican dancehall, is the Caribbean in those samples,” says Campbell. Those samples include Chaka Demus & Pliers’ hit dancehall single Murder She Wrote as well as Dust a Soundboy by Super Beagle.

“There are various black experiences that are connected through the music, primarily though sampling and production,” Campbell adds.

For a time, bits and pieces from black cultures could be found throughout Toronto’s black music but it was the introduction of the vastness of the internet that would be one of the deciding factors for the Toronto Sound. Campbell says that what was once born out of black people’s cultural and ethnic backgrounds was now being influenced by music globally.

“There was a lot more Caribbean influence in ’91, ’92, ’93, ’94 probably up until ’98, ’99, and then once the internet changed everything, it just became harder and harder to find a Caribbean influence because everyone is exposed to a lot more.”