Being Fit to Fly

A crash, a conversation about

mental health and the stigma

that still exists in aviation

By Samantha Campling

Losing their license and job is a fear many pilots have. Photograph by Sam Campling.

Warning: This story deals with issues such as mental illness and suicide. If you are in crisis due to mental health, call the Canadian Crisis Hotline at 1 (888) 353-2273.

Prologue

I began working towards my private pilot’s licence in 2017, during the winter semester of the first year of my undergraduate degree. Growing up around bush planes in the northern Saskatchewan town of La Ronge, I would hear the sound of dual-engine Twin Otters, transporting up to 13 fishermen or mine workers at a time, and the single-engine Beaver — smaller but just as helpful for hauling gear — taking off on floats every morning in summer. My father was a Twin Otter captain and would routinely take me with him on drop-offs and pick-ups. This experience nurtured my love for flying. I received my “little blue book” the summer after I started training, showing that I was now a licenced pilot. I knew I would only be flying for fun and that my passion for being airborne didn’t soar quite as high as it did for the people I knew who were career pilots. But as long as I could pass my Category 3 medical examination every five years, I would be set — free to take to the skies whenever I wished.

I passed my private pilot flight test on June 8, 2017, making me a licenced private pilot. Photograph by Sam Campling.

Before I’d fully immersed myself in my training flights, I went to a small clinic in Saskatoon to have my exam done by a Civil Aviation Medical Examiner (CAME), a physician who was appointed by Transport Canada to ensure pilots were safe to fly. The clinic was on one the city’s main streets, but was still difficult to find, being mixed in with 10 other businesses all using the same parking lot. I can’t remember if it came first or last, but the one thing I vividly recall from the exam was that I had to pay $125.

As I sat through my exam in that medical office in the spring of 2017, I wasn’t worried about the questions the doctor and nurse were asking. Whether they prodded me with instruments or just asked about the state of my mental health — with a single question — and even though I’d be dealing with mental health challenges of my own soon after, my readiness for flying was never in doubt in my mind. But as I was going through that exam four years ago, the rest of the aviation world was still grappling with a catastrophe that had happened two years earlier, and which would begin to shine a critical spotlight on routine medical tests for pilots.

![]()

Chapter 1

The Crash — And The Question

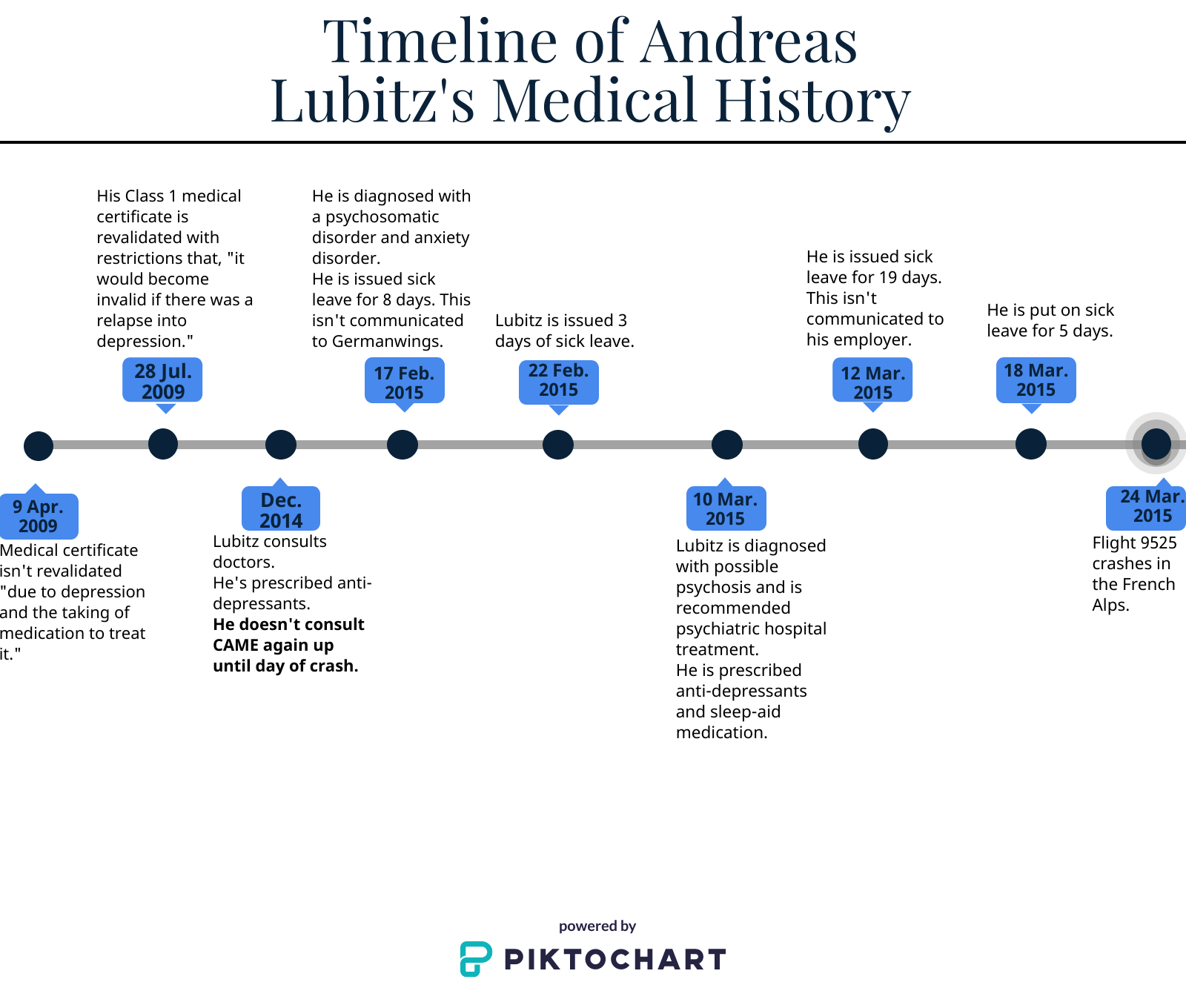

At 6 a.m. on March 24, 2015, Captain Patrick Sondheimer, 34, and his co-pilot Andreas Lubitz, 27, took off for Barcelona from Düsseldorf, Germany in an Airbus A320 for the German airline Germanwings. Sondheimer and Lubitz were seated side-by-side at the controls, except when either pilot left the cockpit. Unbeknownst to his captain, Lubitz took the opportunity — each time Sondheimer was out of his seat — to practise what he planned to do on the return flight.

The aircraft landed at Barcelona at 7:57 a.m. and its 144 passengers disembarked.

At 9 a.m., Flight 9525 took off from Barcelona for the return trip to Düsseldorf with 144 passengers and six crew members on board, including the two pilots and four cabin crew. Once at the planned cruising altitude, 38,000 feet, Sondheimer left his co-pilot at the controls. This is when Lubitz’s practice sessions became real.

With Sondheimer out of the cockpit, the selected altitude on the autopilot changed from the cruising level of 38,000 feet to 100 feet. A slow and steady descent began.

Four minutes after Sondheimer had left the captain’s chair, the buzzer to request access to the cockpit sounded. There was no response. Thirty-three seconds later, the intercom came on then three subsequent calls were made via the interphone. Each time, there was no response. Sondheimer desperately tried to gain access to the cockpit. But all of his attempts to do so would be ignored by Lubitz.

Flight 9525 continued its downward course. Forty-one minutes after the takeoff from Barcelona, the aircraft collided with the side of a mountain in Prads-Haute-Bléones, in the French Alps. The impact was catastrophic. Everyone on board was killed.

The mysterious crash drew world-wide media attention. Soon, investigators were trying to unravel what had happened.

France’s Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses pour la sécurité de l’aviation civile, the country’s air crash investigation authority — best known by the acronym BEA — began a formal investigation into the causes of the crash. Meanwhile, a research team in Boston — based on initial reports that suggested Lubitz may have deliberately slammed the jet into the mountainside — began looking beyond the crash, asking a deeply disturbing question that would soon confront the aviation industry in the wake of the Germanwings tragedy: are airline pilots depressed?

The study was published in 2016. The first of its kind, it was led by Alexander C. Wu from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health with the goal “to provide a more accurate description of mental health among commercial airline pilots.” It was an important undertaking, according to the study’s introduction, because this kind of data hadn’t been attainable in prior studies on the subject since researchers had lacked methods of ensuring the anonymity of pilots contributing to the research.

The resulting Harvard report explained that “hundreds” of commercial airline pilots are flying while concealing their symptoms of depression, “perhaps without the possibility of treatment due to the fear of negative career impacts.” The study, published in the journal Environmental Health, was conducted by sending an anonymous web survey to airline pilots around the world between April and December 2015. In a later post for a research blog series by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Wu stated: “Although this study relied on self-reports and represents a small sample of airline pilots, it indicates that there may be a significant number of working pilots suffering from depressive symptoms.”

Nearly 3,500 airline pilots from more than 50 countries participated by answering a series of survey questions. 1,837 surveys were completed and the rest were partially finished. To assess whether the participating pilots met the criteria to be considered clinically depressed, the study included a PHQ-9 evaluation. This is a Public Health Questionnaire that assesses a respondents’ reported experience of depression through a one-page exam with nine questions and a rubric-style answer guide, with answers ranging from zero (“Not at all”) to four (“Nearly every day”) in response to questions about specific symptoms or experiences.

Of those who took the test, more than 12 per cent met the criteria for currently having depression (with a score of 9 out of 10). And out of the entire survey cohort of 3,485, four per cent of respondents — about one in 25 of those surveyed — reported having suicidal thoughts during the two weeks prior to completing the survey. The survey also noted: “Pilots who reported using medication to aid sleep and who experienced sexual or verbal harassment were significantly more likely to be depressed.”

The study was conducted surveying male and female pilots, but researchers said they were especially interested in surveying female airline pilots and their mental health.

A year after the Germanwings tragedy, in March 2016, the final report was released by BEA. The report included 110 pages of direct evidence from the crash, as well as expert analysis, conclusions from the investigation and a series of safety recommendations.

The outlined cause of the crash, according to BEA, was “the deliberate and planned action of the co-pilot who decided to commit suicide while alone in the cockpit.”

Chapter 2

Flight 66

Twenty days after the Germanwings flight crashed in France, another plane went down in mountainous terrain in British Columbia.

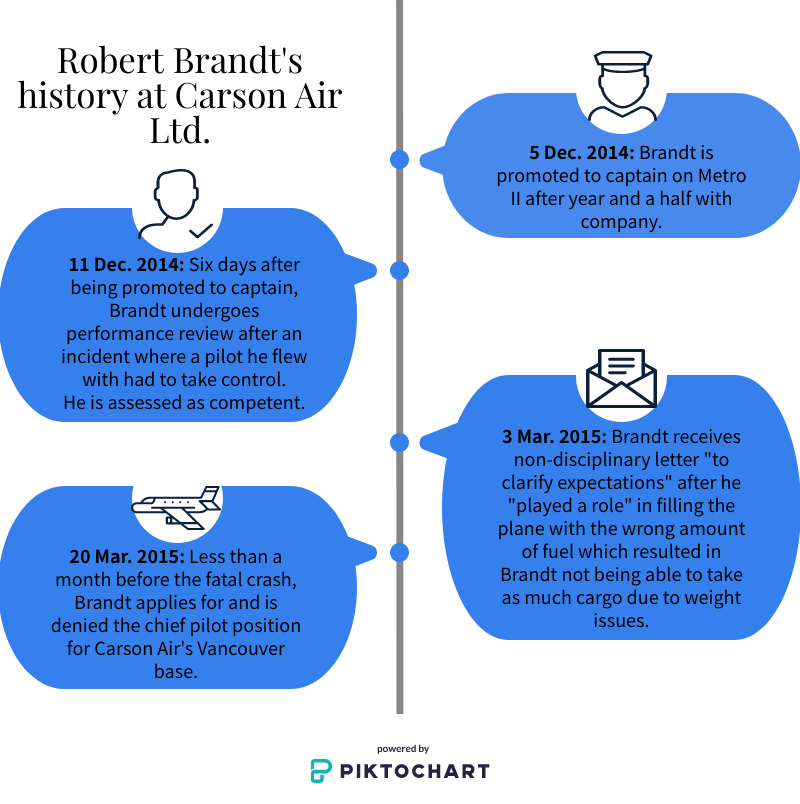

On April 13, at 7:03 a.m., Carson Air Ltd. Flight 66 took off from Vancouver International Airport en route to Prince George, B.C., with only captain Robert Brandt, 34, and co-pilot Kevin Wang, 32, aboard the Swearingen Metro II aircraft. The flight was part of an 800-kilometre cargo run between Vancouver, Prince George, Dawson Creek and, finally, Fort St. John in the northeastern part of the province.

The pilots’ last radio call was heard at 7:07 a.m. by the CYVR control centre at Vancouver airport, where air traffic controllers give instructions to pilots in the designated airspace. Those instructions must be followed.

At approximately 7:10 a.m., Flight 66 was in a steep descent to the ground. Stresses from the speed of the descent caused structural breakup of the aircraft while it was still in the air. The plane then crashed into the side of a mountain in North Vancouver.

The cause of the crash is disputed within the final report conducted by the Transportation Safety Board of Canada, but each scenario points to the captain, Brandt, having a blood alcohol level of 0.24 — three times the impaired driver threshold of .08 millilitres of alcohol per 100 millilitres litre of blood, though, at the time, pilots were not permitted to have consumed any alcohol for eight hours prior to a flight. Due to this accident, in 2018, regulations were amended and pilots now are not permitted to consume alcohol for 12 hours before flying.

A timeline of issues related to Brandt’s employment with Carson Air. Graphic by Sam Campling.

According to the first possible scenario laid out by investigators, Flight 66 went down due to pitot system icing, which means an outside air intake that measures airspeed iced over, causing the pilots to become unaware of the true flight speed — and which could have led them to start descending to ensure they wouldn’t stall the aircraft. The report explained that the captain’s impairment could have caused Brandt to forget to turn on the anti-icing system.

The second scenario pointed to both pilots being incapacited, but the report explained that investigators were unable to find evidence of the co-pilot being incapacitated.

The final scenario outlined the possibility that the crash was a deliberate act by a suicidal Brandt. According to the report: “The well-publicized, deliberate Germanwings flight into terrain only 20 days before this occurrence, combined with the fact that the captain had a high BAC and was the pilot actively flying the aircraft, focused the investigation’s attention on the potential for the captain to have committed an intentional act.” The report also noted that, “the captain exhibited physical-health indicators of long‑term heavy alcohol consumption, which included cirrhosis of the liver and coronary artery disease. These conditions are common outcomes of untreated alcohol abuse and dependence, which are associated with increased risk of suicide.”

But an intentional act as the cause couldn’t be confidently confirmed: “Although there were several coincidental factors, the investigation could not make any conclusions about the captain’s predisposition to committing an intentional act.”

The Transportation Safety Board’s final report on the B.C. crash couldn’t definitively identify the cause, partly due to the lack of a voice recorder in the cockpit. But with any aviation tragedy, there are direct causes and indirect ones — systemic factors that underlie and contribute to the context in which a disaster becomes possible. And in the earlier report on the fate of Flight 9525 in France, BEA explained that while it was Lubitz’ choices that ultimately led to the tragic crash, it was ultimately the system that failed Lubitz.

That report stated: “The process for medical certification of pilots, in particular self-reporting in case of decrease in medical fitness between two periodic medical evaluations, did not succeed in preventing the co-pilot, who was experiencing mental disorder with psychotic symptoms, from exercising the privilege of his licence.”

The “self-reporting” provision requires a pilot to go to his or her aviation medical examining doctor and disclose any illness — physical or mental — that would affect their flying capabilities. The BEA report went on to explain why the principle of self-reporting was subject to failure. The cause of the Germanwings crash, ultimately, was “the co-pilot’s probable fear of losing his ability to fly as a professional pilot if he had reported his decrease in medical fitness to an AME.”

Lubitz’ mental health affected his career from the beginning of his flight training in 2008. Graphic by Sam Campling.

The report also explained that Lubitz may have decided to continue working to avoid losing his medical certificate because he feared the loss of income — particularly because of the lack of insurance available to Lubitz and needing to pay off a 41,000 € loan he used to pay for his 60,000 € flight-training fees.

Lubitz did have insurance through Germanwings. For the first five years of their careers, all pilots with Germanwings and Lufthansa (Germanwings’ parent company) had loss-of-licence insurance to compensate for lost income should they become unfit to fly. This insurance would have given Lubitz a one-time pay out of 58,799€. But he wasn’t able to get any additional insurance.

According to BEA, Lubitz wrote in an email the waiver on his licence was “hindering his ability to get such an insurance policy.”

Chapter 3

The Licencing

Back in the Saskatoon doctor’s office, a middle-aged nurse took me to the back of the office, made me pee in a cup that would be checked for blood sugar levels, and then escorted me to another room. There, she had me sit down, take my glasses off and tell her what I could read on a poster on a wall six metres in front of me. She quickly learned that everything I saw without my glasses was a blur. So I redid the test with my glasses on and I was sent to the doctor’s examination room.

There, an older man checked my pulse, my blood pressure, my breathing and my hearing. He asked me a couple questions about my overall health. How much alcohol did I drink? Did I use drugs or smoke? How was I feeling — the only question asked about my mental health. Generic and ambiguous. Then we chatted about books I was reading and books I should read.

I didn’t pay attention to all the nuances of the medical examination. I knew very little of what they would be checking me for. Eyesight, hernias, blood pressure, nothing that seemed too nerve-wracking to me, a healthy 19 year-old who hadn’t had any medical issues throughout my life besides the chicken pox and a run-in with pneumonia that lasted a week when I was nine.

An hour and a half after I’d walked into the clinic, I left with a “passed” exam that would be sent to Transport Canada for my licence.

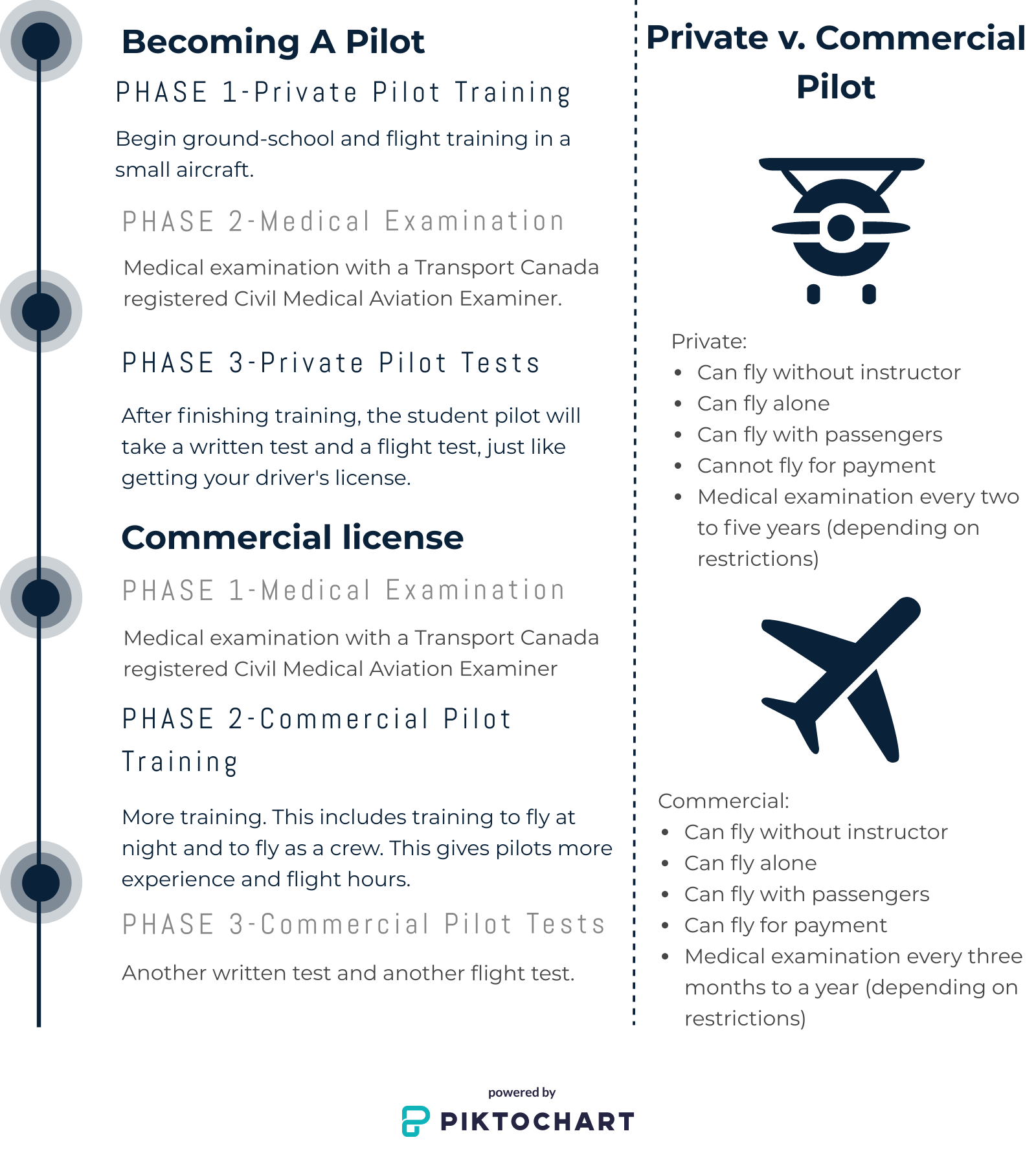

![]()

To receive and continuously hold a valid licence to fly, pilots must meet the medical standards set by the federal government’s transportation authority, Transport Canada. In order to receive approval for this certification, pilots will first be assessed by a Civil Aviation Medical Examiner, a physician specially appointed by the federal transport minister. These doctors are found across Canada. They are, for the most part, regular physicians whose patients include any member of the public, not just pilots.

Getting and maintaining a commercial pilots licence requires pilots to follow many steps. Graphic by Sam Campling.

The one difference between these doctors and others not appointed by the minister is their expressed interest and added training in aviation medicine provided by Transport Canada — which is an important distinction, according to Dr. Brendan Adams.

Adams is a family physician and CAME based in Calgary. He holds a certificate of special competency in addiction medicine, as well. Adams is also the assistant medical director of flight operations for WestJet, a medical consultant for Jazz as well as for a variety of professional pilots’ alcohol and drug rehabilitation programs, including those offered by the Airline Pilots Association (ALPA) Canada.

“One of the problems is that aviation physicians are generally trusted and liked by their pilot clients,” he said. “It’s a little closer than the family doctor relationship because (the pilots) realize you hold the power over their licence. There used to be a standing joke in aviation that your average pilot had two doctors: one he told the truth to and the other one was his aviation doctor.” But with all physicians, including CAMEs, being able to access a pilot’s health record online, this distinction has been blurred.

Adams said during a standard aviation medical examination, the doctor follows the prescribed form created by Transport Canada, asking the pilot questions and jotting down their answers — exactly what I experienced during my initial medical exam in Saskatoon.

The examiner will then look through the pilot’s medical history and ensure both sets of information line up. Most of these questions, though, are based on a pilot’s physical health rather than any indicators of mental health challenges.

According to Adams, this form is followed throughout the examination, but for mental health,

CAMEs may need to veer from it a bit if needed. Photograph by Sam Campling.

To assess mental health, Adams said, “There isn’t a potted set of questions . . . Which is why, if you’re a good civil aviation medical examiner, typically you’ve done family practice for a long time. So you’re supposed to have that skill set.”

He explained there are formal questionnaires to help, “but more typically, what you’re doing is a narrative history where you start with very open-ended questions, as you might expect your family doctor to: ‘Tell me how you’re feeling. Tell me about your sleep. What’s your appetite like?’ You know, all of those kinds of things. You ruminate about things, down to more specific questions.”

During our interview over Zoom, myself at home in La Ronge, Saskatchewan and Adams at his office in Calgary, I asked whether there are other CAMEs who don’t get into the depths with these questions.

“Any competent family physician — psychiatry is a large part of what you do,” he answered. “So it’s not that I find that doctors don’t know, I find that sometimes, bluntly, they’re rushed. They don’t have time.”

He continued: “So unfortunately, in general practice, you’ll find that too often you get short shrift. Aviation can be like that; the pilot doesn’t really want to tell you, the doctor doesn’t really want to ask, so there’s almost a conspiracy of silence.”

Chapter 4

Grounded: Shavonne’s Story

From December 2019 until March 2020, Shavonne Perreault had a difficult choice to make that — unbeknownst to her at the time — would affect her life for the next year. She had to decide whether to keep dealing with her sense of sadness and overwhelming feelings of depression while remaining on the job, in the cockpit of a Swearingen Metro II aircraft, for B.C.’s Carson Air Ltd., or get the help she wanted to make herself feel better. She knew that seeking help meant she’d be losing her Category 1 medical certificate — her licence to fly — for an unknown length of time.

“There’s so much unknown,” she said. “You don’t know what’s going to happen. I still kind of don’t.”

Perreault flew the Metro II until March 2020, when she had to put her passion on hold to get the mental health help she knew she needed.

Photograph submitted by Shavonne Perreault.

Perreault had to take the time to understand her options.

“It’s weighing, like, ‘I’ve spent this much time, energy and expertise,’ ” to get to her position as a captain, she said. “Versus, what do I need to do to be healthy? What would be better for me as a human?”

But another problem arose as she was contemplating her options. Her flying isn’t just a career; it’s her passion — and a core part of her personal identity.

“Flying makes me happy,” said Perreault. “So, if I lose that, will this cause a relapse? Will all my effort be for nothing? I was, like, do I pull the trigger on this in uncertainty? Will these meds help me anyways? Maybe they won’t, and I won’t fly ever again.”

With all of these questions piling up in her mind, Perreault decided the smartest thing for her to do in that moment was ask. She reached out to Transport Canada anonymously, using a fake email, to ask what would happen to her career as a pilot if she decided to start taking SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) — antidepressants that increase the amount of serotonin as neurotransmitters and ease symptoms of depression.

“Unfortunately, they never responded,” she recalled.

So she contacted a CAME she knew to be an advocate for pilot mental health in the aviation industry.

“I said, ‘Hi, I’m Shavonne. I’m a pilot. My medical is due (soon) coincidentally but at the same time, I would like to go on SSRIs. What’s going to happen to me?’ And they replied with a little bit general information. They weren’t too specific about it.”

These experiences left Perreault with little to do but research the situation for herself. CAMEs follow a regulated guide book, Transport Canada’s Handbook for CAMEs, that is available to the public online. Perreault read through this, finding the information she would need to better understand how long she would have to be on SSRIs — while grounded by Transport Canada — to establish a competency in her abilities as a depressed pilot who’d been successfully treated.

Perreault then took her next steps. In March 2020, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, she went to her family doctor and got a prescription for an SSRI. Once she left the doctor’s office, she emailed her manager to explain that she was grounding herself in accordance with the Canadian Air Regulations (CARS) and would follow up once she knew she’d be able to come back to work. Four months later, feeling like she had a better handle on her mental health situation and was ready to return to piloting, she went to her CAME. She explained what she was doing and explained that she was ready to take the next steps for her recovery.

When she went to her CAME, she was told Transport Canada required a pilot to be on the SSRIs for six months before they can be properly assessed and — as Perreault was hoping — get back in the cockpit. In addition to completing the six-month medication period, Perreault needed a letter from her doctor outlining her treatment and its positive outcome. The CAME physician then had to complete a PHQ-9.

“Until you get a chance to educate people on it, I feel like their first impression is depression equals suicide, depression equals you’re not going to be a competent captain, or you’re going to sabotage this flight in some way.” — Shavonne Perreault, pilot

Once each step was completed, Perreault’s CAME put all her information along with the exams and additional evidence into a case file.

“Then they sent it to Transport, and I haven’t heard since. It’s been almost a year,” Perreault said. “I just wish the government didn’t make it such a difficult process because I feel like I’d be a better employee” since being treated.

During the past year, Perreault said she’s reached out to her CAME for updates multiple times. With the case currently being analysed in Ottawa by the federal transport ministry, Perreault said her CAME has asked and received the update of “someone is still looking into the case” each time. While Perreault waits, unable to work without her medical certificate, she is getting financial support from Unemployment Insurance, but she also gets help from her husband. “I guess the worst part is, I’m lucky enough. My husband works but if I was living on my own, I’d be in poverty. What would I do for work? My education has been geared towards flying.”

When asked about lack of updates to Perreault and the delay in the decision about when or whether she can return to the cockpit, Frédérica Dupuis, a senior advisor in the communications department for Transport Canada, stated over email: “The decision to issue or renew an aviation Medical Certificate is based on a thorough risk analysis with aviation and public safety as the primary considerations. Transport Canada has issued guidance (such as the COVID-19 Guidance for the Canadian Aviation Industry) to the Canadian Aviation Industry with respect to mental health and continues to monitor the situation. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Civil Aviation Medicine continues to experience significant operational delays in processing medical certificate applications. However, it continues to process applications as quickly as possible.”

While Perreault came to terms with seeking help despite grounding herself and thus being on leave from her job, she also grappled with the stigma of being — as she called it — a “mentally-ill pilot.”

“When you mention to people, ‘I have depression,’ they kind of freak out a little bit,” she said. “They kind of treat it like, ‘Are you going to crash the plane?’ Until you get a chance to educate people on it, I feel like their first impression is depression equals suicide, depression equals you’re not going to be a competent captain, or you’re going to sabotage this flight in some way.

“Especially my company has a little sensitivity to it,” Perreault continued, talking about Carson Air Ltd. and the 2015 crash involving Brandt. “So our company is a little sensitive to mental health. From a management level, they’re sensitive in a good way, but from a pilot level, they are sensitive like, ‘Are you going to kill me?’”

Chapter 5

The Stigma: She’s not the only one

Three years after gaining my pilot’s licence, I hadn’t flown a plane in about 11 months. I had been busy with school, lacking funds to afford to rent a plane in the city and was working a summer job in my hometown, where there weren’t even planes to rent. I was also dealing with an illness that may have been relatively invisible to those around me. But it had become increasingly apparent to me that I needed help, whatever that looked like. At the time, I didn’t fully know what it was, but I now know I had anxiety.

I booked an appointment with a doctor in my hometown — who also happened to be a CAME — and was going to talk to him about what was going on with me and potential treatment options.

I told a close friend of my plan. A commercial pilot working in the north, he looked startled as the words left my mouth. He was sympathetic to my issues and knew I just wanted to get better. He understood my concerns, but he also understood the aviation side of the story better than I did.

“You should be careful what you tell him, you know,” he said.

“Why?” I asked. I was tired and desperately wanted to feel better, or to know if I could feel better. I wanted some direction at the very least.

“If you tell him too much, he could take your pilot’s licence away.”

![]()

Like Perreault, other pilots feel this sense of stigma when deciding whether to talk about or take action for their mental health. And according to Suzanne Kearns, associate professor of geography and aviation at the University of Waterloo, these issues have engulfed the aviation industry for quite some time.

Through her research into human factors in aviation, Kearns talks about how in the 1970s, multiple airplane crashes occurred in which the reason for the crash was blatantly pilot error.

“It really put a lot of focus on the person. It became less about, ‘Can you maneuver?’ and ‘Can you learn this?’, but more about what is the right attitude,” Kearns said. “So, they created training programs like what’s now called crew resource management training (CRM). And what CRM training is really focused on is what we call ‘non-technical skills,’ skills like communication, crew coordination, workload management and situational awareness.”

This training is now required for all working commercial pilots in Canada, solidifying the increased importance placed on interaction between crew members in the cockpit. Kearns said this is a great step forward to ensure pilot mental health is being thought of by companies, but it’s still not the perfect solution.

“The challenge is still the idea that pilots have to maintain their medical certificates in order for their licence to be valid, so if at any point, they’re feeling overwhelmed, or any sort of other materialization of mental health challenges, there’s a strong incentive for them to not disclose that, and therefore to not seek treatment for that, because they’re worried about losing their medical.”

Kearns continued to explain that for many people, when you lose your licence, you could lose your job.

“The way that things are set up right now, it’s basically encouraged to lie, because it’s a lot easier.” — Luke Matchett, pilot

Brittany Varga, a co-pilot on a King-Air 200 — a 13-seat dual engine aircraft — in Saskatchewan, has experienced this thought first-hand.

Varga, who said she doesn’t have a mental illness, attends regular therapy sessions. These began before the COVID-19 pandemic, but have increased in frequency since she had to quarantine after a trip out of Canada in early March 2020.

“Everyone has down days. But since COVID-19, it’s just been so different because you’ve been completely cut off from the world,” she said.

Varga was also laid-off from a co-pilot position, her first job as a career pilot, in March because of the pandemic. “It’s like you didn’t really have anywhere to turn to.”

When asked if she feels she can talk to her co-workers or management about mental health in general, as well as her own, she said, “Definitely not. I have not told a single co-worker or anybody in management.” She said the macho ideals of the predominantly male-dominated industry are a factor as to why she felt she couldn’t. The other reason she felt uncomfortable discussing these issues is the medical assessment process.

“We’re governed so much by our medicals and I think anybody is scared to say anything if it’s going to affect (their) medical, potentially, because that’s their job,” Varga said. “For some people, depending on how old (they) are, it’s not easy just to go and get another job. Some people don’t have other degrees. They can’t fall back on something.”

Luke Matchett, a captain on a De Havilland Dash-8 400 based in Calgary who has been furloughed for the past year, has heard from colleagues who want to get mental health help, but feel as though they can’t.

“I have had multiple people come and speak to me about their own issues, and talk about how they would love to see a counselor or something like that, but they can’t over fear of losing their licence, and losing their career,” he said. Pilots are able to seek counselling and won’t be penalized, unlike when being prescribed medication, however there’s still this perception.

Matchett has also heard from individuals who want to become pilots, but their past struggles with mental health stand in the way.

“I just had my medical yesterday. And the exact question that they asked (me) is, ‘Have you ever been diagnosed with a mental health illness or taken medication for mental health illness?’” he said. “I know somebody who (was) trying to become a pilot. He answered yes to (those questions), because he had some issues like 10 to 15 years prior to this. And it took him over two years to get a medical after that.”

Matchett said those two years were filled with evaluations from different doctors and “a ton of paperwork.”

“The way that things are set up right now, it’s basically encouraged to lie, because it’s a lot easier,” he said.

As the person on the other side of the pilot-assessment system, Adams was asked whether pilots ever willingly come forward with information about their mental health being anything other than normal.

“It’s a very complicated answer, and partly depends on (the) kind of pilot and where they’re working,” he said. He explained that if you’re an airline pilot for a company like WestJet, “you’re fully covered by a disability plan and you’re represented by a union, so I find that those guys are actually fairly forthcoming.” But, he said, if there isn’t a company or any extra insurance in the case of a loss of licence to back the pilot, they tend not to come forward with their issues.

“A mom-and-pop crop duster operation where you’re in over your head, you’re in hock to the bank for the airplane, you’ve got to keep flying and you’re the only one that flies it — heck no, you’re not going to tell me what’s going on because you know darn well if that medical goes south so does your whole business.”

But issues still remain for airline pilots, as well, and this stems from the priorities of Transport Canada and other aviation regulatory bodies around the world, according to Adams.

“There’s always this creative tug of war in aviation between the regulatory demands to protect the public, which is all that the minister is really interested in. He doesn’t care about your mental health — (or) maybe if he’s a nice guy, he does. But generally, what he’s gonna say to you is: ‘I’m just concerned about Canadian public safety.’ So, the government comes in and can sometimes be very heavy handed, and encourage people to go and hide.”

Chapter 6

A ‘Lucky’ One: Tom’s Story

Like Perreault, Canadian pilot Tom — who asked to only have his first name used so he couldn’t be identified due to fears of being stigmatized in the industry — had his medical certification suspended because he began taking anti-anxiety medication.

A co-pilot based out of Toronto, who also asked that his plane not be mentioned as it would easily identify him, Tom was a private pilot at the time but was hoping to eventually gain his commercial licence and start flying as a career.

“That was really tough — one, because I didn’t just want to lose the passion, but also my biggest fear at the time was losing the possibility of ever making it a career,” Tom said of making the decision to get the mental health help he felt he needed.

“I (went) on anti-anxiety medication because of things going on in my life, but more specifically to the job I was working at the time,” Tom said. He was on this medication “for about six months, and I noticed that in combination with lifestyle changes, and this medication, my mood started to improve.”

Since, according to Transport Canada’s Handbook for CAMEs, a pilot with an anxiety disorder who is actively getting treated cannot hold a valid medical certificate, Tom was grounded. But the grounding was only for six months, as he then stopped taking the medication after deciding that the best way to help himself was to make lifestyle changes and see a counselor instead.

“I had it fairly easy,” he said. “I know a few friends right now who are going through the same process for similar conditions and identical medication, and it hasn’t been that easy. Some of them have been waiting up to a year and I only had to wait maybe a month or two,” Tom said of the time he spent waiting to hear if his medical certification would be approved or not after he stopped taking the medication.

“When I initially got deferred, I thought, ‘Hey, game over for me.’ I’m probably not going to get it, I’m probably going to have to wait a year. I won’t be able to apply to flight school. But getting my letter in the mail, that was the greatest feeling ever.”

“You can’t be an effective pilot if your mental health isn’t where it needs to be.” — Tom, pilot

While a working commercial pilot, Tom still worries about colleagues finding out he’d had a mental illness in the past.

“To be honest, I’m still very much afraid they’d be afraid to fly with me,” he said. “There is one pilot at my company who I know I can open up to full disclosure and he understands every aspect of it. But it’s hard to find those people without actually bringing up the conversation itself.”

But although he felt this way, he still advises other pilots, if they’re experiencing difficulties with their mental health, to get help.

“You can’t be an effective pilot,” he said, “if your mental health isn’t where it needs to be.”

Dr. Brendan Adams’ sentiments echoed Tom’s statement.

“People ask me what it’s like when you’re sitting — say on a WestJet flight or a Canadian North flight — and you see somebody from your rehab program get on to fly the airplane. And my answer is, I relax, because I know he’s awesome. He’s the one we caught. The guy that’s with him that we haven’t caught yet — that’s the one I’m worried about.”

Chapter 7

The Big Players: Major Canadian Airlines and their Supports

The Canadian airline industry has two major organizations that cover a majority of daily flights to and from the country’s major airports: Air Canada and WestJet, and their partner airlines. These airlines also employ a big portion of Canadian airline pilots, with about 3,600 employed by Air Canada and its partner airlines, and about 1,200 employed by WestJet and its partners, before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pilots at each of these airlines are represented by various unions. For pilots at Air Canada and Air Canada Rouge, the representation is through the Canadian Union of Public Employees. The pilots at WestJet, WestJet Encore, Sky Regional (a partner of Air Canada) and Jazz Aviation (a partner of Air Canada) are represented by the Air Line Pilots Association.

Through ALPA, there is a program called Pilot Assistance, which provides mental health services in different capacities. One of these is the Pilot Peer Support Program. Murray Munro, a captain for Jazz Aviation and former chairman for ALPA’s Pilot Assistance Program, explained that for pilots, peer support is needed.

“It gives the person — the pilot that’s having difficulties — the ability to speak to someone that understands them, speaks the same professional language and understands the stressors.” Peers within this program are also trained to help the pilot figure out the cause of their issue and then, potentially, provide the pilot assistance with finding a counselor, or other mental health professional. The peers are also called upon to contact pilots who have had an incident during a flight.

“But the ugly reality of addiction, — and I would say depression and anxiety, as well — is that a trust bridge is built much more quickly, and is much easier to reinforce, when the person you’re talking to is also a pilot, understands what the industry is, understands what that pilot’s role is and how it works.” — Ian Gracie, pilot

“Anytime there’s an incident at work that might be stressful for a pilot, say an emergency in-flight of any kind, the company has an emergency call out system that fans out to all the managers and all our volunteers,” Munro said. “We’ll get an email and a telephone call with a message that gives you all the pertinent details, and when these pilots are on the ground, and in a safe place, we’ll contact them, and debrief them or talk to them or defuse them. And by doing that, again, they have an outlet to talk to somebody in confidence.”

Confidentiality is a major reason that this type of program works for pilots according to Munro. “All of this is done with the strictest of confidentiality. The confidentiality is a huge part of it. Because if you don’t have the confidentiality, pilots don’t trust management, (so) they’re not likely to be forthcoming with us.”

But Pilot Assistance within ALPA isn’t only the peer-support program. Pilots represented by the union are also able to get knowledgeable, and confidential, help when they believe they may be facing a mental illness, or any illness for that matter. “We champion Transport Canada to help them get their medicals back and we find them the right medical information that they may need,” Munro said.

Within the aviation industry, because of these pilot assistance programs, Munro, who has been a pilot since 1984, said he thinks the stigma surrounding mental health in the profession is getting better.

“There was a huge stigma back decades ago, as in any industry, where pilots were worried that if they came forward with a mental health issue, that would be the end of their career. Things have progressed today to the point where, with the guidance from a pilot assistance program or a peer-based program, pilots understand that suffering from depression or having a mental illness isn’t the end of your career anymore.”

However, it’s important to remember that many pilots at small airlines within Canada still aren’t represented by a union. Some of these companies, like the one Brittany Varga works for, have Employee Family Assistance programs (EAP), which provide insurance funding for specific professional help.

But, Munro said these EAPs aren’t perfect. “The only issue that we’ve had with pilot assistance and sending somebody to an EAP is that (they’re) large companies, usually. So if you have a mental health issue, you can call (the EAP). They’ll send you to a psychologist or psychiatrist or whatever is required. And let’s say you (are put) on a restricted medication. (The psychiatrist who prescribed it) not being aware that that particular medication is prohibited as a pilot.” This would then cause the pilot to lose their medical certification and be unable to fly.

Ian Gracie, a captain for WestJet and chair of ALPA’s WestJet Airlines Master Executive Council (WJAMEC) Pilot Recovery Program, sees the stigma as still being strong.

“In society in general, there’s still a stigma around addiction and mental health and it’s somewhat magnified in the aviation industry, because of the pilots’ fear of having their category one medical revoked by civil aviation medicine,” he said.

Gracie, with his experience of being an alcoholic in recovery for the past 22 years, helps other pilots through the Pilot Recovery Program with some of the same challenges he faced.

“The primary goal is to get the pilot in healthy recovery, and secondarily, get him back to work under our program as well as the civil aviation medicine standard,” Gracie said.

“The program was created to present education and awareness around addiction and addiction recovery for pilots, but also to identify guys that are suffering, and then have them professionally assessed, attend treatment, and then following treatment, come into our monitoring process, which is a minimum period of five years.”

The program is peer-based. And confidentiality, as in many of the other programs for pilots, is held to a high standard. But the peers who run this program are other recovering pilots, which Gracie said is instrumental.

“To a lay person, (it) would seem either unforgivable, or an immense threat to flight safety, whereas I can look at that and say, ‘Yeah, I’ve done that, too. It’s not smart. It’s not good for anybody. But I understand how you got there.’”— Ian Gracie, pilot

“It needs to be peer-based and peer-led, and managed by other pilots in recovery,” he said. “The pilot that I’m talking to becomes instantaneously aware that I understand what he’s going through and what he’s afraid of, based on my own experience. There has been much discussion about (the idea that) anybody should be able to help pilots who are suffering. And there’s a certain truth in that any human being with care, compassion and empathy can love and care for another human being, and be influential in the solution.

“But the ugly reality of addiction, — and I would say depression and anxiety, as well — is that a trust bridge is built much more quickly, and is much easier to reinforce, when the person you’re talking to is also a pilot, understands what the industry is, understands what that pilot’s role is and how it works.”

In addition to this, Gracie said recovering pilots are able to tell others, who have gone through the same kind of things, what may have happened while flying because of the disease of addiction.

“To a lay person, (it) would seem either unforgivable, or an immense threat to flight safety, whereas I can look at that and say, ‘Yeah, I’ve done that, too. It’s not smart. It’s not good for anybody. But I understand how you got there.’”

Like other programs, the WJAMEC Pilot Recovery Program helps pilots who are suffering mental health challenges navigate the tricky territory of getting treated without fully losing their medical certificate. But again, this is only for a specific group of pilots who are employed through one of Canada’s largest airlines.

Chapter 8

The Aftermath: Flight 9525 and the EU

Germanwings Flight 9525 was a wake-up call for the international aviation industry. But it directly changed the European Union aviation field. As a result of the crash, and through recommendations from the BEA, a key regulation was amended. One revision, designed to change aspects the medical portion of pilots’ licences, was implemented on Aug. 14, 2018; the other key reform, making changes to the operational side, was to be implemented by companies by August 2020 — but because of disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, wasn’t put into effect until Feb. 14, 2021.

The change to the medical side of the regulation imposed added psychological testing on the initial medical examination for all pilots in the European Union — commercial and private. As Dr. Cristian Ionut Panait, a medical expert for the European Union Aviation Safety Agency in the Aircrew and Medical Department, explained: “It’s not only a psychological (examination) but it’s a full mental health assessment with a psychiatrist, psychiatric evaluation and so on, to try to identify existing pathology or to identify reasons to believe that certain conditions could evolve later to a pathological problem.” The amended regulation also added a new required test to all medical examinations: drug and alcohol screening.

The revision also affected the industry from an operational standpoint, which is why this aspect of the major reforms was implemented later than the changes to medical requirements. The amendment added a different psychological test that ensures the pilot and operator — the airline, its flight-scheduling system and other operational factors — are a good match.

“This (revision) is intended to actually make sure that the psychological profile of the pilot matches the profile of the operator in terms of operations,” Panait said. “We have persons that work better in the morning and persons that work better in the evening, persons that cannot go without 10 hours of sleep per night and things like this.”

Panait continued: “And it depends on the type of flying that operator has; if they are airlines, or if they’re cargo. If they fly short haul, medium haul, long haul. So if you have somebody that needs to have breaks (often), then maybe an operator that has short haul (and) flies less than one hour might be more suitable for that person, rather than having a flight of 12 hours — (a) long haul flight.”

This amendment also requires operators to “enable, facilitate and ensure access to a proactive and non-punitive support programme that will assist and support flight crew in recognising, coping with, and overcoming any problem which might negatively affect their ability to safely exercise the privileges of their licence.”

The regulation further states that the information provided by the pilot during support sessions must remain private, unless keeping it private goes against any other laws.

“The more complex idea was that we need to find a way to help people.” — Paul Reuter, pilot

Why peer support rather than certified counselor sessions?

“Because this is one of the things that makes aviation in particular a bit special. Pilots are a special breed,” Panait said. “They are some sort of a closed society, where they do not open up so well towards outsiders. It’s easier to speak with somebody that has a similar experience to yours, than going to speak with somebody (who) has no understanding of your environment and all of your problems.”

“Mental health is difficult for anybody to discuss,” Panait continues. “One of the first symptoms of every medical mental health issue is denial. And that’s the first stage — we all deny that we have a problem. But that’s what we are trying to achieve. To go beyond this initial phase faster, by helping (pilots) to open up to people they know and to people that understand the environment, and this way to gain a bit of time before the issue becomes too severe.”

One of the organizations that gives advice to companies going through the process of setting up a peer-support program, such as through a guidebook, is the European Pilot Peer Support Initiative. EPPSI was created in parallel with the EU understanding that pilots needed support for their mental health after the Germanwings crash in 2015, according to chairman and Boeing 737 captain Paul Reuter, who was also on the EU Commission Task Force looking at the accident.

“It was because we were seeing that there was a lot of talk (during the investigation), the low hanging fruit is always: ‘OK, we need to do more psychological assessment of people. We need to do drug testing,’ and whatnot. But the more complex idea was that we need to find a way to help people,” Reuter said of the idea behind the creation of the organization.

But again, there was the question: Why peer-support specifically?

“The difference is that in a lot of these professions like law enforcement, probably the military and then pilots, we don’t trust doctors. We don’t trust psychologists for the simple reason that there’s always a potential that they can take away your licence. However, as a pilot, whether you’re in the cockpit or after a flight, people tend to open up because the guy you’re talking to has the same experiences (as) you. He has the same stresses probably; family issues — you’re never home, or you’re never home at the right moment and stuff like that. These peer support programs try to take advantage of that.”

On top of not being home often, pilots also hold the immense responsibility of all the lives on board their aircraft. This responsibility is often amplified by passengers, putting extra pressure on pilots to never make mistakes.

While these programs seem to be on track to help the aviation industry in Europe, there’s another issue: what will it cost the operators? These same airlines have been losing vast amounts of money each quarter over the past year due to the pandemic. And are the reforms going to be worth the investments in terms of better outcomes for pilots and greater safety for the flying public?

Panait said it’s too early to tell.

“Somebody has to pay for these support groups and in most of the cases it is the airline. The problem is it’s not possible to quantify, ‘how many accidents did we prevent with implementing this’,” Panait said. Because they are unable to provide a number for this to showcase the potential of these policies, Panait said they need to follow expert opinions for now. “We’ll be able to quantify maybe in 10 years if we realize that the number of accidents and incidents which (are) trigger(ed by) a mental health issue are less, based on the reports, then we can put them behind these measures, but at the beginning, we cannot quantify.”

In their study on airline pilots and mental health, Alexander Wu and his team made a recommendation. Despite the importance placed on new evaluations, which the study said isn’t the way forward, the EU seems to be following the conclusions made by the study with their peer support measures. The conclusion of the study reads: “The tragedy of Germanwings flight 4U 9525 should motivate further research into assessing the issue of pilot mental health. Although current (in 2016) policies aim to improve mental health screening, evaluation, and record keeping, airlines and aviation organizations should increase support for preventative treatment.”

Chapter 9

Looking Up

The European reforms represent the leading edge of positive change when it comes to addressing pilots’ mental health challenges. Canada and the U.S. have much to learn from the European model. But some good things are happening on this side of the Atlantic, such as a national pilot substance abuse recovery program that doesn’t discriminate by company or union, and an app that will take a pilot’s mental health and make it a part of their everyday life.

Ian Gracie is not only the chair for the recovery program at WestJet. He’s also the chair of a budding national substance abuse recovery program.

“What doesn’t exist in Canada is a national addiction program for pilots. So in Canada, you have the WestJet program, there’s a Jazz Aviation program, and then limited programs (otherwise), but there’s no national community working on that problem for pilots,” he said. “So the project that we’re now working on is called Aircrew Recovery Canada (ARC). And the goal of that is to create that national structure for addiction recovering pilots in Canada.”

He explained the program would be designed similarly to what is in place at WestJet now — the Pilot Recovery Program — but its reach would be nation-wide.

“It would be more of an overarching body to help guide individual airlines to build their own programs based on the experience of WestJet, and Jazz,” he said. “Then we’ll be working in collaboration with Transport Canada, civil aviation medicine, the treatment community, as well as individual airlines management systems so that what we create is a community that is properly trained and understands what the goals are so that everyone in the industry is pulling on the same rope, in essence, to properly support and help the clients, but also to reduce stigma through education, awareness training around addiction and mental health.”

The first goal of the program, according to Gracie, is to help airline pilots. But he understands that those are pilots who already have these resources, so the goal would be to help more.

“The ultimate goal is that it doesn’t matter if you’re starting day one of flight school, or you’re on your last day of your career, headed for retirement or even if you are in retirement, if you’re suffering from substance abuse or addiction, you can pick up the phone and call this ARC number and speak with somebody who knows what to do,” he said.

Gracie said the proposal for the program was approved by the ALPA Canada Board in September 2019. At that point, he explained, the plan was to have the program up and running in five years. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has lengthened the implementation timeline.

Three aviation students from the University of Waterloo are looking into a way to destigmatize the conversation on mental health in the industry by allowing pilots to self-report their mental health through a phone app. The three students — Noah Rawlinson, Matt Mawdsley and Christopher Brukner — all took an Aviation Safety class taught by Suzanne Kearns. The idea for the app they are creating came from a group project for Kearns’ class. Brukner explained they thought of it as they were researching mental health in aviation.

“Imagine the day when you talk with your mental health, like it’s a cold — like, ‘Oh, I got cold today.’ It’s like, ‘Oh, I’m feeling kind of not great today.’” — Noah Rawlinson, pilot and app developer

“We had found that while there is a lot in aviation happening around mental health, (and) many airlines do seem to have programs where pilots can reach out to and get help, it all seems very dependent on the individual experiencing mental health problems to go out of their way and get the help that they need,” Brukner said.

Brukner explained that while some companies do require initial mental health screenings when a pilot is hired and there are the annual examinations by CAMEs, the initial screenings aren’t recurrent and the annual medical exams aren’t in-depth.

“We found that our app would be putting a requirement on thinking about mental health and forcing it a little bit more into the mainstream.”

One of the reasons they decided to take on this project, according to Mawdsley, is because they’ve experienced the stigma directly.

“Being the fact that we’re pilots, and we kind of experience this day to day, especially in flight school when it’s pretty fast paced, and pretty stressful, we have a relation to mental health and how it affects us,” Mawdsley said. “Especially because we’re flying and going to school, there’s a lot of balancing to do there. And we know that the IMSAFE checklist that we’re supposed to do before every flight is kind of brushed aside and no one really does it. When you have a bad day and you have to go fly later on, it’s not a good flight. So imagine that with 200 people behind you.”

The IMSAFE checklist is taught to student pilots at every flight school in Canada. It serves as a pre-flight risk assessment tool, and all pilots are advised to complete it before the flight. The checklist goes: I(llness) M(edication) S(tress) A(lcohol) F(atigue) E(motion).

The app they hope to create will have three main components. The first would be a daily self check-in in which the pilot could rate their mood on a scale from one to 10. “That will help make it easier for pilots to start thinking about mental health and bring it into their every day a little more, rather than some kind of hands-off topic that only gets brought up at ground school every now and then,” Brukner said.

The second component is where the pilot would be paired up with a colleague, giving them the space to connect on a day-to-day basis. The third component is also specific to the company the pilot is working at. This part of the app would hold all mental health resources in one easily accessible place.

“The idea (behind this component is like) iPads at the airlines,” Rawlinson said. “Pilots use their iPads to pull out (landing) approach plates and stuff like that, so that (they) can figure out how to get into an airport. The idea is that you can pull up an approach plate as easy as you can pull up mental health resources and help. So whether it’s a pilot at the airport, or a pilot who needs help right away, they’re just as easy (to get to).”

The goal for the app is ultimately to destigmatize thinking and talking about mental health in the aviation industry.

“Imagine the day when you talk with your mental health, like it’s a cold — like, ‘Oh, I got cold today.’ It’s like, ‘Oh, I’m feeling kind of not great today,’” Rawlinson said.

“I think that we need to build the aviation industry to support the future. We need to reflect our practices towards where we should be, not where we’ve been before.” — Suzanne Kearns, aviation professor

Kearns also sees a benefit to bringing app technology into the discussion on aviation and mental health. She said an app can help pilots with self-monitoring, for example. But, she said, it can’t do everything to improve the current situation.

“I think ultimately we have to see this sort of organizational shift for the entire culture of the industry, to recognize that you can be strong and capable and competent, and still suffer sometimes from mental health issues.”

During our interview over Zoom, both in our respective home offices, I asked if schools would be the ones to provide this change.

“I think a lot of it will come from the next generation,” she said. “I think the younger generations have a better and healthier attitude towards people’s differences and supporting people who are different in many ways. So I think when it comes to mental health, specifically, I think the younger generation is more accepting of that.”

But she added that if these students get a job at a company that isn’t working to change the stigma, their voices won’t be able to carry as much weight.

“I think that we need to build the aviation industry to support the future,” said Kearns. “We need to reflect our practices towards where we should be, not where we’ve been before.”

Epilogue

On that day, 11 months after my last flight, I did go see a doctor in La Ronge. He was also one of the area’s CAMEs. I told him my symptoms and simply explained, ‘I just want to get better.’ He asked me a few questions from a chart on his computer used to assess mental illnesses. He explained that I probably had anxiety, but didn’t diagnose me formally. I’m not sure if he was trying to do me a favour — making sure not to delve into my mental health to avoid placing my pilot’s licence at risk — or if he was just genuinely busy that day, as Dr. Adams explained is often the case. He gave me some options of approaches I could take — attend therapy, see a psychiatrist to get assessed and potentially be given a prescription for medication, or go to a psychologist and get a full assessment. This was great advice, and he did help give me a bit of clarity. But the potential solutions he offered were options I’d need to pursue on my own.

The meeting didn’t ultimately give me enough clarity to know what to do next. The treatment options would involve concerted action and commitments of time and energy, and the decision — at that time — was too great for me to make on my own. I left his office uncertain about the best way forward and uneasy about my mental health — but still a licenced pilot.

In a year, I’ll be going to get re-examined for my Category 3 medical certificate. If all goes well, I’ll be able to continue flying. Maybe that doctor knew what he was doing. Maybe he knew the risk of me disclosing my mental health troubles would be too great, that it would put my licence at risk. I don’t blame him.

There needs to be transparency in medical approval updates to pilots. There needs to be honesty on the time it could take to get approved after revealing a mental illness and in the requirements to get the medical certificate reapproved if denied. There needs to be a more open conversation between pilots and their doctors about mental health, one in which those who fly are encouraged to speak openly about the stress, anxiety and even depression they may be feeling in their lives, so that they can get the treatment they need without fear — except in severe cases — that they could be grounded for their honesty. We should look to the new EU aviation regulations and their increased preventative measures such as peer support for all pilots, no matter the company, and their in-depth mental health check during an initial medical examination.

As I walked into the doctor’s office in La Ronge, I thought I’d begun a new journey, but I left pretty much on the same track. Maybe this makes me one of the ‘lucky’ ones, because I’m still deemed ‘Fit to Fly’.

![]()