Saving language at the edge of the world

How the Skidegate Haida have whispered their language back from the brinkBy Jensen Edwards | May 2018

Gidahljuus Eddy Hans shuffles through the door of his Haida language class in the beachfront cedar longhouse in Skidegate, B.C. A half-hour late and leaning on walking canes, he squeezes a CD case in his left hand.

“Morning Ed,” shouts teacher Kevin Borserio from the front of the vaulted room. Borserio is nearing retirement, but his students, for the most part, are well into theirs. Hans nods, pushes past his classmates and hands over the CD. The teacher snaps it into the ghetto blaster. The loud sound of a finger-picked guitar starts up.

Before the music break, the participants of the Skidegate Haida Immersion Program (SHIP) were translating house names from the now-uninhabited Haida village of Skedans. The names are common knowledge for most of them, but if the people at SHIP don’t translate them now, no one will know how in 10 years’ time.

Gaayinguuhlas Roy Jones Sr., one of the pillars of Haida language knowledge at SHIP, is from Skedans. The 94-year-old former fisherman turned SHIP student is the one who requested this morning’s music.

The same lilting strings and smooth twang in “Help me Make it Through the Night” that won Sammi Smith a Grammy in 1971 once carried Jones Sr. and his wife, Yang Kaalas Grace, across a community hall dance floor on an island off the north coast of British Columbia.

“They used to win every contest,” classmate Sgaamsgid Harold Williams Sr. says, taking a break from singing along out of time. “I used to try like heck to beat them, but I couldn’t. They were so smooth.” Today, the Joneses sway in their seats. Walkers are too cumbersome to slow dance with.

Backlit by the grey window light filtering through his translucent hair, Jones Sr. nods along. Between his wife and Borserio, he pauses to call up another SHIP elder, Percy Williams, formerly Gidansda, a Skedans chief. Williams used to lead the Skidegate swing band on saxophone, providing the soundtrack to the Jones’s prize-winning dances. “He would play it real nice,” Jones Sr. says.

Above the heads of the elders at work, Williams’s portrait now hangs alongside those of more than a dozen others, each crowding the next and pinned into the orangey-red wooden walls of the longhouse. Poster boards with collages of field trips and school visits document the lives of people who dedicated their last years going to school from nine to three each day, speaking their language into microphones, recording it in the hope that their grandchildren might one day learn a tongue that was stolen from their own generation.

K’uust’an tlldagaaw unguu || Crab on top of the mountain

Click here to play bilingual story

K’uust’anaay tlldagaawaay unguu tay guuhlana gan.

The crab was lying on top of the mountain.

HlGaagilda k’iidaay gii xaaydas tluu giidal gyinuu k’uust’anaay

xiidgii ‘ll xaagad gyinuu xaayda skal gii ‘la tl’lxiidang.

When Haidas paddled through Skidegate Narrows,

the crab would reach down and pinch their shoulders.

Xaayda kil sk’aadgayaay gam xaangaala kwaajuuwaay ‘laa gans.

Gaaganah.

Because the Haida language wasn’t progressing fast enough.

This is why.

All recordings in “Saving language at the edge of the world” are courtesy of SHIP and FirstVoices.ca

What it means to

have a Haida name

For the Haida, names are gifts, tokens bestowed on descendants by elders who deem a particular name appropriate to the character of the person. They can be inherited or created. In the case of Gidansda, the name traditionally falls to the hereditary leader of the Raven clan of Skedans (an anglicized version of the chief’s name). After Percy Williams died in 2017, the name was passed on to his nephew.

“People say it’s an honour to receive someone’s name,” says Cle-alls John Kelly, who is Skidegate Haida. He was given the name Cle-alls at a potlatch—it was also the name of his grandfather. But receiving a name, he says, is much more. “It’s a responsibility.”

Cle-alls means “fireweed,” and carries connotations of a powerful speaker. But Kelly’s voice is breathy and hollow; he doesn’t have the booming vocals someone might immediately associate with the name. However, his cousin Yahldaajii Gary Russ jokes that the former journalist and language expert speaks softly so that people around have to pay attention.

As a family heirloom, “the carrier [of a name] has the responsibility to leave it in as good [of] condition [as] how they received it,” Kelly explains.

“When you’ve reached the edge of the world, you’re here”

In 1998, a handful of Skidegate Haidas lobbied their band council to fund a school program to document every syllable of their language before the meaning behind the sounds passed away with their elders. They recognized that without action, future generations would not hear their own histories in their own language. Twenty-one years on, a thousand-page glossary weighs down bookshelves around Skidegate and another 280 CDs loaded with recordings have been produced by SHIP. More and more learners are taking up the language here every year, and every year, fewer fluent speakers return to their posts.

“Want us to clear out the table there?” Borserio asks Jones Sr., pointing to the space inside the horseshoe of desks that is cluttered with a fold-out table piled high with reference books and budding lady slipper flowers. “You and Yang K’aalas can slow dance there. We’ll all just close our eyes and pretend we’re in dreamland.”

The driving rains, gliding eagles and scavenging ravens that fly in and out of frame beyond the floor-to-ceiling windows behind Borserio inspire daydreams for SHIP’s students, as swells from the Hecate Strait break and batter Skidegate’s long pebbled beach. To the south, thick veins of deep green spruce and cedar trees cut through the archipelago. In the north on Graham Island, where the students of SHIP and most people on Haida Gwaii live, extensive logging has shaved much of the original growth from the ancient black rocks. But on the ground, humans are dwarfed by the greenery. On the Galapagos of North America, trees can grow faster than almost anywhere else on earth. It’s no wonder that the Haida have become legendary for protecting the earth around them. At SHIP, between portraits of Elders and maps, t-shirts and posters hang, protesting pipelines and tankers.

This photo was taken on the beach at Skidegate in the late 1800s, likely by Haida Christian minister Peter Kelly, John Kelly’s grandfather. Kelly, the elder, assembled Skidegate Haida on the beach for a mock potlatch to document the regalia of his relatives. Potlatches were banned in 1884 under the federal Indian Act. [Photo courtesy of the UBC Museum of Anthropology, image ID 2005.001.334]

Colonial resource exploitation started on the islands over 200 years ago, when the first Spanish ship drifted up to Haida shores in 1774, and it has continued ever since. The Europeans saw tens of thousands of bobbing fur coats, hats and blankets in the sea otters that lined the coast, towering cities, grinding mills and hulking armadas in the endless forests that stood taller than their homelands’ spires. By 1802 the commercial harvest of sea otters had peaked. That summer, a single British trapper collected more than 15,000 pelts; by the middle of the century the animals had disappeared from Haida Gwaii.

Waves of Spanish, then English traders, hunters, colonists and missionaries also eroded the Haida population. Beginning in 1862, smallpox ripped through more than 12 of the Haida villages, ranging from the southern point of the archipelago at SGaang Gwaay to Kiusta in the north. Over 20 years, the disease cut the Haida down from nearly 10,000 to fewer than 900. A need for sustained healthcare forced people to retreat to two main villages on Graham Island, Skidegate and Old Massett. When the smallpox abated, a new colonial threat emerged in the form of Confederation.

The Canadian government began by banning all potlatch ceremonies in 1884. The community gatherings where chiefs distribute wealth and people celebrate with feasts, dances, and songs had served as traditional forums to host marriages, mourn deaths and mark other life events in the community. The new law threatened any individual caught hosting a potlatch with a six-month jail term. So, the Haida held secret potlatches under the guise of birthday parties, church meetings and other government-accepted occasions. For nearly 100 years, traditional language, teachings and songs were whispered in secret moments away from the ears of Indian agents.

A 1951 amendment to the Indian Act withdrew the potlatch ban, but a lifetime of state-sanctioned persecution of cultural practices through residential schools, legislation and adoption policies had beat out much of the language, spirituality and traditional knowledge culturally specific to the Haida.

“We’ve withstood [centuries] of exploitation, attempts at annihilation, and we’re still here,” says Cle-alls John Kelly, a language worker and teacher who helped create SHIP. “We might as well do it with our languages since we’re going to be here anyway.”

Generations after their language and culture were initially threatened by colonial governments, members of the Haida Nation took it upon themselves to repair what years of legislated cultural repression and racist policies tried to eradicate. They would bring back their language on their own.

Kelly’s cousin Yaahldaajii Gary Russ was on the Skidegate Band Council when the first formal language revitalization program was proposed in 1997. Russ, 74, understands some Haida from his childhood, but he’s still learning to speak it at SHIP.

Russ’s parents used to speak it, but they never passed it on to him. “The only time they talked Haida,” he says, “was when they didn’t want us to know what they were talking about.

“The government frowned on us using our language, even to the point of spanking and strapping kids in the school system if they tried to use their own language.”

Russ only took up re-learning his nation’s language upon retirement in the early 2000s.

“I’ve had a fight for funding, for the continuation of the program, and I even had to fight some of our own people who wanted to close the program down. But we worked through it and here we are today. We’re successful and I think, I know, we have our language saved.”

“We’ve withstood [centuries] of exploitation, attempts

at annihilation, and we’re still here.

“We might as well do it with our languages

since we’re going to be here anyway.”

–Cle-alls John Kelly

The sign for Xuuya Raven Street in Skidegate is covered with lichen, fostered by the sea winds and near constant winter rain. [Photo © Jensen Edwards]

A raven gathers its congregation on the lawn outside SHIP with rich, guttural rumbles that seem to mimic the “loaded K’s” being practiced by Xaayda kil learners inside. K’, or “K-underline tick,” is one of several consonants that get caught in the unpracticed throats of anglophones new to the language. The Haida K alone has four variations: K, K’, K, and K’. Ticks, which serve to indicate that the sound is pronounced as a quick “pop,” can also follow other sounds like t’s and ts’s. The underline indicates a rumbly and guttural aspiration, akin to the raven’s rolling call.

Of the more than 60 Indigenous languages spoken in Canada, Haida is unlike any other. It is a language isolate (meaning it has no other language relatives, like French has with Spanish and Italian, for example) consisting of three main dialects: Alaskan (Xaat kil), Masset (Xaad kil), and Skidegate (Xaayda kil). While a Xaayda kil speaker and a Xaat kil speaker can mostly understand one another, the three varieties themselves are aggregations of many more that were whispered out of existence with the decimation of the Haida populations of the northwest coast of North America in the 19th and 20th centuries. The elders at SHIP wrestle with fragments of upwards of 19 dialects in order to come to a consensus on any given translation. When no one solution can be settled on, they write down and record all of their options.

A tonal difference

Underlines, ticks and emphasis can all drastically change the meaning of a word pronounced. Take, for example, the case of “uncle” and “littleneck clam”. Both have the same vowels and only vary in the underline of one letter.

Uncle | KaaGa

Listen

Littleneck clam | Kaaga

Listen

Spelling aside, “It’s way easier to read than English,” says Jones Sr. The orthography that SHIP uses is clear and consistent because the sounds match the letters and never vary. Unlike English’s classic -ough trap, with practice, Haida sounds become natural to read. “So, when you know the sounds, you can read it all,” Jones Sr. adds. “It’s easy.” It’s why, every morning at SHIP, Russ can effortlessly read the 14 lines of the Haida version of the Lord’s Prayer taped into the back of his agenda.

Nonetheless, even that takes practice. Jones Sr.’s assertion assumes that a reader can speak the sounds cleanly to begin with. But while an infant has the capacity to distinguish between and recreate sounds not regularly spoken in the language that surrounds them, that ability is quickly lost by the time they’re up and walking. It becomes even more difficult to activate long-dormant muscles that may not be used in a speaker’s first language. For an English speaker learning Haida, proper pronunciation takes years of repetition, embarrassment and a patient learning partner.

Niis Waan Harvey Williams, right, is one of eight fluent speakers who regularly serve as the voices of authority at SHIP. The former logger and fisherman turned to teaching the language in his retirement. [Photo © Jensen Edwards]

Sounds like hl bring out laughs from experts. “The trick,” says fluent elder Niis Waan Harvey Williams during a coffee break in class, “is to make sure there’s lots of spit coming out the sides.” The phoneme is pronounced with an open mouth and a curled-up tongue, arched towards the back of the throat like a breaking wave. The air of an exhale gets caught in the tongue and is forced into the cheeks beside a speaker’s lower mid-molars, before dribbling out the corners of the mouth. Inexperienced speakers fumble and turn it into a lisp, or more embarrassingly, into two parallel waterfalls of spit falling down their chin.

Hl, like Skidegate’s Haida name, HlGagilda (listen). The name means “becoming stone,” like a pebble, swirling in the eddy of a creek, becoming more and more round. The English name, Skidegate, is itself a deformation of an 18th-century Haida chief’s name. Then-chief SGiidagids—meaning “child of chiton”—gave his name to an English trader, who used it as a toponym for the area.

Haida words can also be made by combining sounds that indicate concepts, including whether they are horizontal or vertical things, made of wood or made of stone. There are few word-for-word English to Haida translations. More often than not, a simple English word or phrase involves finding the appropriate sentence in Haida. Take, for example, Xuudaay ts’aap’ad gaay siilaay gii tl’aaw da kaadtl’lxa. Though the phrase translates loosely as “You came here when the seal already went down,” the sentence is used commonly to say, “You’re late.” The English expression is just an imprecise pronoun, a simple verb and a temporal observation. But translated into Haida, it becomes a cultural revelation.

The Haida language also reaches beyond phonetics and symbols to call up cultural references in the simplest expressions. Yahguudang is a good example. It is the expression used for the English word, “Respect.” “The essence of a chief,” Kelly says, explaining the translation. “It’s something that you feel in somebody who has that spirit. When they walk into the room, they don’t really even have to say anything. You just feel it. They live their life demonstrating it. That’s respect.”

,,Like when a more recent Chief SGiidagids, Dempsey Collinson, whose portrait is pinned high on the cedar classroom wall at SHIP alongside former classmates, learned that a family had moved onto his land without permission or notice. The lifelong fisherman, who had revolutionized the herring roe industry by fostering sustainable harvesting practices with Jones Sr., went to meet the new family. Upon learning that they had few belongings and nowhere else to go, Collinson welcomed them to his village with heaps of groceries. He told them, “I noticed you don’t have much to eat,” recalls Kelly, “and nobody goes hungry on Chief SGiidagids’s land.” That, Kelly says, is yahguudang.

The respect in the classroom at SHIP goes both ways. Borserio’s dedication as a teacher was honoured when he was adopted into the Ts’aahl Eagle clan and given the Haida name Luu Gaahlandaay—“wave spirit.” At the same time, he knows that his students have the final say on translations. The Haida are a nation of perfectionists, and when it comes to recording a phrase as simple as Dii guudang.ngaay k’iina (“I am happy”) —the pace, the pause and the k-tick all matter.

When SHIP first started, Kelly would spend hours re-recording simple phrases with fluent elders like SGaana jaads K’yaaga Xiigangs Kathleen (Golie) Hans, until they were satisfied that learners at SHIP, and younger students at the high school where Hans teaches, could hear the particularities of their pronunciations. To emphasize the sounds even more, Kelly deployed a technique used by the British in the Second World War to better encrypt their messages sent through undersea cables. He added a 0.05-second delay between the left and right speakers. “In speakers, it just sort of sounds like everything’s in a hollow room,” he explains. “But in headphones, the ears are isolated, so to a non-native speaker the unique sounds pop.”

Fluent speakers’ crisp enunciations are vital for SHIP students like Eddy Hans, whose eyes strain to decipher the letters on his page. Instead of hunching over worksheets to peer through his two magnifying glasses, the lifelong musician relies on his well-trained ears to pick up the subtleties in his classmates’ pronunciations so that he can echo back phrases when the students take turns going around the horseshoe of desks, practicing their skills. But like a game of telephone where one slip-up knocks the whole message off course, a mispronunciation by a classmate can mess up Hans’s own contribution, turning a phrase into gibberish, or giving it another meaning entirely.

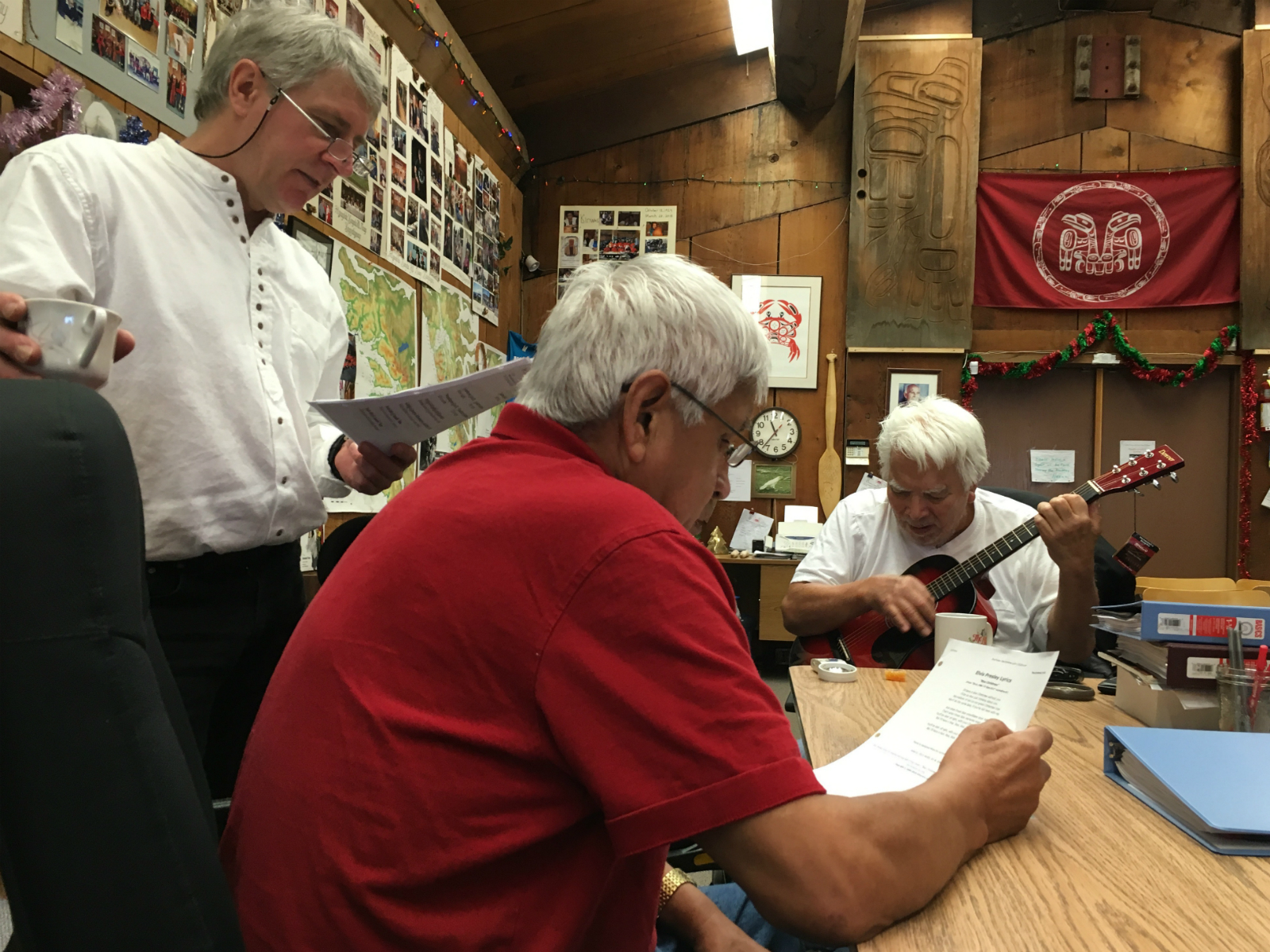

Kevin Borserio, standing, Sgaamsgid Harold Williams Sr., centre, and Eddy Hans sing Elvis Presley’s “Blue Christmas” in December 2018. [Photo © Jensen Edwards]

You can almost feel the difference [in the tones],” says Joanne Yovanovich, the Haida language coordinator for the Haida Gwaii School District. Even as someone who is far from fluent, she likens hearing Haida to “listening to good music that just goes through yourself and through your soul.”

Yovanovich’s mother, Ada, was a fluent speaker and a contributing elder at SHIP, but those lessons didn’t reach her as a child. “When we did hear her,” Yovanovich says, “it was to her family and usually that was stuff we weren’t to hear about.” She says that shame and stigma overrode any linguistic pride her mother had for a long time. “Because residential school,” she sighs. It’s a common refrain among people talking about the language of their ancestors, of which they were robbed the opportunity to learn. That’s why before they could record and teach the language again, so many of the elders at SHIP had to re-learn the language they had heard in their childhoods. Because residential school.

Ada Yovanovich never went away to school. Her father did but he held onto two things afterwards: his language and the resolve to never let his children go through the same experience. Grown up, Ada married a non-Indigenous man and consequently lost her Indian status, as per federal legislation at the time, which was upheld until 1985. (Despite amendments, Canada still discriminates against women when it comes to Indian status, according to a recent report for the United Nations Human Rights Committee). This only compounded the elder Yovanovich’s hesitancy to speak or share the language with her own children. But by 1976, with her eldest daughter at her side, she began teaching Haida language and culture classes at the school in the neighbouring logging town to Skidegate, Queen Charlotte, known in Skidegate Haida as Daajing giids . “They were really nervous to do that,” says Yovanovich, “because of that not-good stigma that came with language and identity.”

The first fluents to share their linguistic knowledge in the school district were not university-qualified teachers. Instead, their jobs were informal, insecure and never guaranteed. It also meant that it was duty to their nation and passion for their Haida identity that drove them, not necessarily the salary.

The non-Haida classroom teachers were making more than double that of Yovanovich, Golie Hans, Sing.giduu (“breaking of dawn”) Laura Jormainien and other fluents. That was in the 1980s, before SHIP and before a formalized Haida language and culture curriculum was introduced to the district. Today, Hans, Jormainien and Taalgyaa’adad Betty Richardson split their time between the longhouse on the beach at Skidegate where they record their knowledge and the schools in Queen Charlotte and Skidegate. Hans looks after the high school lessons, Jormainien works with the elementary school students and Richardson makes sure that Skidegate’s youngest learners at the preschool have a strong start to learning Haida. Each teacher is still paid less than their school district counterparts, and at over 80-years-old each, they are all still driven by the same things that pushed Ada Yovanovich into teaching over 40 years ago. Hope and duty.

Under the canopy of cedars and spruces in the forest behind Skidegate, rain tumbles down from branches. [Photo © Jensen Edwards]

The rain drives hard and sideways in December on Haida Gwaii. After five days of off-and-on power outages, participants at SHIP delight when Percy Crosby bursts through the building’s cedar doors.

“Ts’iljii” someone exclaims, seeing that the Skidegate representative for the Council of the Haida Nation has entered carrying plastic grocery bags that are stretched by a dozen brittle and thin boards of orangey pink. Ts’iljii means “dried fish,” and to the people at SHIP, it’s as good as candy.

What makes it taste even better is eulachon grease, says Harvey Williams. In lieu of that, SHIP student Gwaalaga Leora McIntyre passes out slabs of butter on teacup saucers. One by one, Crosby gives out the foot-long strips of dried salmon, first to the elders, then to the others in the room.

Williams gleefully slices off a chunk of butter with the sharp edge of his fish strip before he’s even finished saying Haawa (“thank you”) to Crosby. Holding his fish like an edible knife, his hands show the gashes of chainsaws and fishing lines, scars from his life on Haida Gwaii. “See my knee?” he says, pointing to his right leg. His patella slipped in his youth and now floats a few centimetres down from where it should be, on the outside of his shin.

The biggest tree he ever felled, he says, was sixteen feet wide at its base, making its circumference about eight times his wingspan. In the woods as a logger, Williams spoke Haida with colleagues as a way to keep their plans for the day secret from their foreman.

Satisfied with his snack, Williams wraps his remaining splinters of ts’iljii in paper towel and stabs it between the pages of his translation binder, like a bookmark, saving the treat for later.

“We cannot wait for another term in office, another decade, another year.

We are losing our last generation of fluent speakers now.”

–Witsuwit’en Cultural Society, 2018

A jar for pencils rests on SHIP’s Xaayda kil glossary. [Photo © Jensen Edwards]

There are nine fluent speakers of Xaayda kil, or Skidegate Haida, left at SHIP, along with a handful more in Skidegate at large. In 1998, the immersion program began with more than 20. Between all three official Haida dialects, fewer than 30 total speakers remain, and most are over the age of 80. But the precarious position of the Haida language is not unique to a few speakers off the west coast of Canada; fluent speakers of Indigenous languages across the continent are dying at a faster rate than students can train their tongues to speak.

Just 12.7 per cent of Indigenous people across Canada have an Indigenous language as their mother tongue. That’s half the total percentage reported in 1996, despite the fact that the Indigenous population in Canada has grown by over 40 per cent over the last 12 years. “We cannot wait for another term in office, another decade, another year,” reads a 2018 plea from the Wet’suwet’en Cultural Society, demanding strong federal Indigenous language legislation. “We are losing our last generation of fluent speakers now.”

Justin Trudeau hauled Indigenous issues to political prominence during the 2015 election when he made a campaign promise that a Liberal government would legislate to protect and help revitalize Indigenous languages, define Aboriginal rights in the Constitution and redesign child welfare legislation. Indigenous people voted in record numbers in that election, applauding the apparent change in priorities from a federal party.

“The promises were considerably greater than what we have almost ever seen before,” said Veldon Coburn, an expert on Crown-Indigenous relations at Carleton University.

But with just two months until the House rises for the next election, the Liberals have already given up implementing an Aboriginal rights and recognition framework during this parliament and only recently tabled bills acting on languages and child welfare.

Bill C-91, An Act Respecting Indigenous Languages, was introduced in the House on Feb. 5, 2019. With it, the Liberals have one last opportunity to make good on their assertion that they are a strong ally to Indigenous peoples in Canada, as they attempt to shake charges that they have been more about symbolism than substance over the past three years. The outlook isn’t great, said Coburn. “I think that 2019 is going to be the year of Indigenous buyers’ remorse,” he warned, “because a lot of Indigenous people put their faith into what Justin Trudeau was selling [in 2015].”

The Liberals have already been forced to delay implementing the rights and recognition framework which aimed to restructure how the government related to Indigenous nations and interpreted their laws. Indigenous critics claimed that the first go-around was not transparent and now the 2015 campaign promise will remain unfulfilled until after the next election, at the earliest.

There are no federal laws that recognize and protect Indigenous languages in Canada. Section 35 of the 1982 Constitution Act acknowledges that Aboriginal rights exist but does not have specific language detailing what they are or what role the federal government has to play in protecting them.

Nevertheless, the federal government, through the Ministry of Canadian Heritage, has been offering some financial support to Indigenous languages since 1998, through the Aboriginal Languages Initiative (ALI). For 18 years, the program supported community-led Indigenous language revitalization projects across the country with roughly $5 million, though there were initially plans for more.

“There was a grand plan to involve industry and the nation and build a centre where any teacher could access any language,” Kelly said of the recommendations. “It died when the government changed.” Prime Minister Harper cut the seed funding in 2007, citing a lack of clear plans from Indigenous communities on how the money would be used. Critics to Harper’s decision say that his justification for cancelling the funding was in fact the very reason why the money would have worked well for individual communities in the first place, because each has its own set of priorities for language revitalization.

Because of what he saw over a decade ago, Kelly is apprehensive to be satisfied by C-91. “I’m glad it’s there, but it needs to go further,” he says. “I’d like to see it contain provisions for resources to help people to do the work that has to be done. I’d like to see it be more than words.”

At the second-reading stage, C-91 “[establishes] measures to facilitate the provision of adequate, sustainable and long-term funding” to go towards language revitalization efforts. It does not say how much money would be up for grabs nor what the grant application process would be. C-91 also outlines the role of a Commissioner of Indigenous Languages, something Kelly, Coburn and other language experts have called for.

It’s important that the commissioner be an officer who reports to Parliament “rather than to the political whims of a minister that’s appointed by whatever governing party,” said Coburn. “They would need to have a great deal of statutory and regulatory bite that they can exert to flex some authority.”

But while the bill does create a commissioner, critics point out that it provides no plan on how funding—projected at around $334 million over the first five years—will be distributed. “Lots of countries have language legislation,” says Tracey Herbert, the CEO of the First Peoples’ Cultural Council in B.C., “but they fail on the implementation piece.”

Herbert and other language experts who have testified to the House Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage say the bill ought to establish a national, Indigenous-led body that would make funding decisions, like that proposed by Kelly in his 2005 report, Towards a New Beginning.

The bill in its current form makes no mention of such an organization, which Herbert envisions to be modeled on the Canada Council for the Arts or her own organization, which provides grants to community-led language revitalization programs in B.C. “It would be there to help take some of the decision making off of the Ministry of Canadian Heritage […] and to be a support organization those [communities] that maybe don’t have a lot of readiness but want to do something,” Herbert said.

B.C. Minister of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation Scott Fraser said in an interview that the FPCC model had “caught the eye of the federal government,” though as of Apr. 15, 2019, after C-91 has entered the report stage in Parliament, no such organization has been publicly put forward by federal officials.

In lieu of an FPCC-style crown corporation, Heritage Canada’s ALI has supported community-led Indigenous language revitalization projects across the country with a pot that grew from $5 million to nearly $12 million in 2017, funding twice as many grant applications that year. In 2018, it doubled again to $34 million after the Liberal government began to build more funds for Indigenous languages into federal budgets.

*ALI has given an additional $6.9 million to national-scale programs. Additionally, all three territories receive Federal language support through Territorial Language Accords and transfer payments. Newfoundland and Labrador did not receive any ALI funding in 2018.

Provinces are also kicking in money to support local languages. In the 1990s, the FPCC, then known as the First Peoples’ Cultural Foundation, operated on roughly $1.4 million per year. But last spring the B.C. government amped up their funding, assigning $50 million over three years to mentor-apprentice learning programs, preschools and other local Indigenous initiatives to resuscitate and grow languages spoken in the province.

“There’s a desperate need for stable, adequate and sustained funding investment in the languages in order to continue with this really important revitalization work,” says Aliana Parker, the FPCC language programs manager. According to a 2018 report from her organization, the expanded provincial support is working, though slowly. Last year, 2,000 more people were learning Indigenous languages in B.C., compared to 2014. Additional funding from the province and the ALI in 2018 also quadrupled the number of mentor-apprentice pairs that the FPCC could support for the year.

On the national stage, Coburn, an expert on Indigenous-Crown relations, says that any further delays from the government on Indigenous-related bills this term could mean jeopardizing the votes of those who supported them in 2015. Should the language bill fail to pass before the writ drops, like the rights and recognition framework has, Coburn said, “it […] holds a gun to Indigenous voters’ heads and says, ‘Remember a few years ago when you came out? If you still want this, you can have it, you just have to give it to us again.’”

Trudeau’s late push to protect Indigenous languages is not a new idea in Parliament, though it is perhaps the first to be taken seriously by legislators. Sen. Serge Joyal has tabled his own version of an Indigenous languages bill three times in the Upper Chamber: in 2009, 2012, and 2015. The first two died when the writs dropped for the 2011 and 2015 elections, after having been stuck at the first reading stage for years. His latest bill, S-212, was frozen at second reading in the Senate for two years before the Liberals finally introduced C-91.

Joyal blames a lack of interest in the issue for failures of his 2009 and 2012 efforts. “When I introduced the first two bills,” he said, “no government recognized that they had a specific responsibility to recognize languages. [In 2009], it was like preaching in the desert.”

At the time, Joyal tabled letters of support from Indigenous leaders to reaffirm the need for language protections. Ghislain Picard, then chief of the Assembly of First Nations of Quebec and Labrador, emphasized an urgent need for Joyal’s bill in his letter. “Unlike French or English,” he wrote, “we cannot go to another country to recuperate a language that may have been lost. Once our languages are silenced on this continent they are silenced forever.”

Even as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was collecting witness accounts from residential school survivors and after Stephen Harper stood in the Commons to apologize for the institutions and their intergenerational impacts, Joyal’s bill sat stagnant. But when the TRC published its 94 calls to action in 2015 and its chairman, Murray Sinclair, became a colleague in the Senate, Joyal saw an opportunity to advance S-212.

Ten years after he first introduced a languages bill, Joyal said that politicians’ priorities have shifted. “The issue of Indigenous languages is a public responsibility,” he said, “now recognized by the government.”

The work in Parliament, however, has not meant much to the toiling elders in Skidegate, where they welcome new learners to their classroom every year. But there is no Duolingo one-year guarantee with Xaayda kil, the Skidegate Haida dialect. It can take over a decade for someone, even if they have grown up within the culture and heard the language spoken by their grandparents and elders, to finesse the nuances of the language.

“There’s always been a steady flow of new people coming in [to SHIP],” says Borserio. The problem is that few new seats need to be added to the horseshoe of desks to accommodate new bodies. Instead, freshman students sit in the seats of elders who now look down from their photos on the wall. “In the last three years, we’ve had eight or nine fluents,” Borserio said. “Five years ago we would have had 13 or 14. The only reason they don’t come is because they pass away—we lose them that way.”

“It’s hard to imagine listening raptly to 60 ceremonial speakers at a banquet, particularly when the language spoken is not one you understand.

But it has been over half a century since so many speeches were made in the Haida language in Skidegate.”

– Article in the Queen Charlotte Islands Observer, July 1998

Nearly 40 years ago, when Ada Yovanovich and Golie Hans and other underpaid Haidas were working at schools in Queen Charlotte and Skidegate to share their knowledge, they heard a different language drift through their classroom doors. Wendy Campbell, a curriculum developer and language acquisition expert, had arrived on-island to help other instructors teach French.

Years earlier, Campbell had quit her job as a French immersion teacher in Coquitlam, B.C., to write the definitive guide on French language instruction, one that shifted the teaching from the tedium of worksheets and fill-in-the-blanks to repetition and action-based learning. Having maneuvered that into a consulting gig, she began touring B.C.’s school districts to help rejuvenate language teaching methods.

“During those years, one of the Haida teachers said to me, ‘Well gee, you’re in all these other classrooms, will you come to mine?’” Campbell recalls. “So I found myself team-teaching Haida without understanding a word.” She worked with classroom teachers and fluent elders to give the students back their own families’ language. Neither Campbell nor the classroom teachers could speak Haida, which meant it was up to the Skidegate community of knowledgeable elders to take charge. “In the case of Haida language, as is the case with so many others,” says Campbell, “it takes a village to create a sentence.”

Eventually, Campbell and then First Nations education coordinator for the school district John Kelly joined forces to craft a crash course in Haida immersion. They would host a 10-day camp for forty students to showcase to the community that the language could be brought back to its vibrant potential.

After two weeks of doing laundry, beachcombing, making lunch and telling stories—all in Xaayda kil—the fluents and their new protégés marched on the Skidegate community hall on July 24, 1998. Leading the charge was Niis Wes Ernie Wilson, a fluent elder, waving atop a fire truck with sirens blazing. Following behind him were Campbell, Kelly, members of the community, supporters and a pair of llamas (not natural inhabitants to the northwest coast) clopping along, all celebrating the initial achievement. At the feast, the graduates of the Skidegate Community Immersion Project stood to speak in their newly learned language.

“It’s hard to imagine listening raptly to 60 ceremonial speakers at a banquet,” wrote Dianne King in the local newspaper a week later, “particularly when the language spoken is not one you understand. But it has been over half a century since so many speeches were made in the Haida language in Skidegate.”

“There wasn’t a dry eye in the place,” recalls Campbell. The paper reported that “the room exploded” that night when she and Kelly told the community that the B.C. Ministry of Education would recognize Haida language as an accredited course necessary for high school graduation and an accepted alternative to French-as-a-second-language classes. The Queen Charlotte Islands Observer (now the Haida Gwaii Observer) called the celebration “The beginning of an era where the Haida language will make a strong comeback, further strengthening Haida culture at a time when politics and jurisprudence seem to be falling into line.”

For Kelly, the immersion camp and celebration were a means to instill linguistic pride in his community. He said elders started dressing sharper and speaking more, it gave them something to believe in and a hope for their language’s future. To ride the enthusiasm, the former journalist and teacher got to work recording a CD with Haida “baby talk,” translations of 126 things that parents say to kids like “Go wash your hands” and “Inside voices.”

“You could walk down the street and you’d think it was for the kids,” says Kelly about hearing the phrases play around the village, “but the parents were attaching themselves to the CD too and you could hear it coming out the window.”

Soon, fluent and newly fluent teachers like Betty Richardson and Gandaa.uu.ngaay Herb Jones were sharing their language with little ones in daycare too, the best place to start learning, according to Kelly. “It only takes two people to save a language,” he insists. “One person to teach it and one to learn it.” After all, he says, it only took one devoted man in Israel to bring Hebrew out from ancient books and temples to launch the language’s permeation back into common parlance. But the elder teachers of Xaayda kil initially had difficulty sticking to the script with the children, say Kelly and Campbell: partly because the elders were fighting the way that they were taught English as a replacement for Haida as children, and partly, says Campbell, because “they’re grandparents and they [couldn’t] stand to see a little kid cry [when they didn’t understand].”

Kelly and Campbell took their initial immersion camp and expanded it into a full-year school program that would bring together fluent elders, former speakers looking to reclaim their language and new learners alike. The Skidegate Haida Immersion Program launched in September 1998 and has built a monumental collection of classroom resources, recordings and translations, all while fighting against a tide of aging and dying knowledge keepers. As the language became more popular in the community, Kelly says, people started carrying themselves with more pride. But it would take much more than a few speeches and recordings to beat back the shame that the first Haida culture and language teachers grappled with in the school district when they began sharing their knowledge. “It’s [been] long and onerous,” says Campbell of SHIP’s work through the years.

“Imagine if someone said to you, ‘Okay, we’re going to put you in a room for years and we want you to think back to when you were a five-year-old and you used to speak a language.

“It takes the dedication that these elders were putting into it to really have this happen.”

Kevin Borserio and participants at SHIP are quick to recognize all of those who have helped the program. This wall of photos near the front of the classroom celebrates people, past and present, who have given their time to save the Haida language. [Photo © Jensen Edwards]

Though class starts at 9 a.m. in the longhouse, Borserio often spends an extra few minutes shuffling his papers at his desk beside the sound-mixing board, as his students find their places and get caught up on last night’s football game or comment on a few new pictures of a classmate’s grandchild.

Today, before any language work can get done, the first order of business is to resolve the case of the modified toilet seat in the women’s washroom. It’s uncomfortable if you don’t need it, say some students. Others are more concerned with the spiders tumbling from the cracks in the cedar ceiling overhead.

“I’m scared they’re falling into my hair when I’m in there,” says 77-year-old student Isabel Brillon. High above the toilet, tucked between the tree trunks that support the roof of the building, spiders make their winter homes.

“I’ll get the ladder from the band office and see what I can do,” says Borserio.

In order to have SHIP certified as a school by the B.C. Ministry of Education, the Skidegate Band Council needed to find a teacher to facilitate the program. They found Borserio, a white high school social studies teacher from the neighbouring town of Queen Charlotte. He had been on-island for 14 years, teaching Haida students, playing basketball with them, and unintentionally proving himself to be the perfect facilitator to helping direct a classful of mainly octogenarians to carve out a vibrant future their language. But like any school students, people at SHIP always find other, more important things to talk about in class.

Like modified toilet seats for people with mobility issues, spiders, cancelled ferries, bingo and dwindling salmon stocks. But the toilet talk has some educational merit. “How’s that for your first lesson, eh?” Borserio asks a visitor to the school. “Just let us know when you have to chiigan.” Chiigan is the Haida word for the verb, “urinate.”

“You have to raise your hand and ask to go,” laughs Jones Sr. He and his wife are the two eldest Haida speakers at SHIP. While Borserio may be the teacher by title, the Joneses and other elders have final say on translations.

“No need to let us know if you need to K’waaGuu,” Borserio adds. “Just turn the fan on after.”

Beyond language instruction, SHIP also offers its collective expertise to translate documents for governments, students, the school district, and today, for a fishing charter business. The idea behind the translations is to give tourists a taste of Haida. But, Borserio says, given the disorder of the original draft, (“red cedar” shows up twice, basic environmental words like “whale” are missing), it seems to be more of a novelty than anything else.

Most mornings, Gary Russ is already sitting in his spot at the back of the horseshoe of desks and downing his second cup of coffee when Borserio arrives at 8:10. Today he comes in laughing, ten minutes later than usual. He had slept in.

The former logger’s t-shirt reads, “Haida Gwaii: When you’ve reached the edge of the world, you’re here.”

“Sorry Luu!” he says to Borserio.

“Don’t let it happen again,” the teacher, at least 15 years Russ’s junior, tosses back, smirking by the photocopier.

While Russ putters about his morning routine, firing up the coffee maker and slathering a couple of biscuits with peanut butter, Borserio zips between his office and his desk at the head of the longhouse, passing out photocopies of the day’s translations.

Gary Russ, right, is reliably the first person at SHIP every day. He was on the Skidegate Band Council when the program was being discussed in the 1990s. For Russ, governments’ recent attention to language revitalization initiatives is okay, but he wants to see SHIP reimbursed for the 21 years it has worked to save Skidegate Haida. [Photo © Jensen Edwards]

Beyond facilitating the school day at SHIP and organizing translation contracts, ferry rides, lunches and medical appointments for his students, Borserio has also prioritized mentoring young Haida adults to become teaching assistants at the school. They’re often people who are looking to connect with their elders, or who left Haida Gwaii for jobs in Fort. McMurray or in construction in Vancouver or who are just looking for some career direction.

Erica Ryan, whose Haida name Gidin Jaad means “Eagle woman,” was one of those young people. When she was pregnant with her first child in 2012 and felt ill among the smells wafting out of the kitchen at her job at Jag’s Beanstalk—where SHIP staff often grab a halibut burger for lunch—Borserio offered her a job as an IT assistant with him.

“I was never exposed to the language [as a kid],” she says, “or taught the language or had even heard the language.” But among the fluent elders, she absorbed the sounds of Xaayda kil and spent her maternity leave on the raggedy orange couch in the corner of the longhouse, listening and relaying the lessons to her newborn daughter.

When a job posting for a part-time Haida teacher came up, Borserio pushed her to apply. Ryan paired up with fluent elder Herb Jones and together they spent 2.5 hours per week with the Kindergarten class and with the first and second graders at the elementary school in Skidegate. Even with few instructional hours, students showed results.

Seeing the small successes and knowing that her daughter would one day be in that class, Ryan started asking the school district why there were no full-time Haida teachers. “They basically said, ‘We need a speaker with the teaching credentials,’” she recalls. The Skidegate girls’ basketball coach saw the requirement—to get a teaching degree—as “the colonial game that I needed to play” in order to get more Haida language and culture instruction into her children’s schools. “Our youngest fluent speaker was in her 70s, as if she was going to go back to university and get a teaching degree. So I was like, ‘Alright, well here I go.’”

“You can’t learn the language and not learn about ceremony and our traditions and our histories and our ways,” she says, about the importance of having language instruction in schools. “It’s all intertwined, it’s all connected, so to me that’s huge.”

Having completed three years of their program, Ryan and her eight classmates now have to move off island to complete their degrees and do their practicums if they still want to become fully certified teachers. Unfortunately, says Joanne Yovanovich, jobs in the Haida Gwaii School District won’t be guaranteed for the students when they return. Neither the money nor the teaching spaces are certain, says Yovanovich. Despite the school district being under the umbrella of the provincial Ministry of Education, First Nations education on Haida Gwaii and across the country is funded on a per-student basis by the federal government. In Skidegate, that funding is falling along with its student population.

The community of Skidegate faces the same situation as its students’ high school. As SHIP loses more and more fluent elders every year, the language it is trying to revive may become stuck in books and recordings, like a specimen preserved in formaldehyde: there to look at, but fundamentally lifeless. “Preservation is what we do to berries in jam jars and salmon in cans,” reads a plaque at the Haida Heritage Centre at Kay Llnagaay (“Sealion Town”). “Books and recordings can preserve languages, but only people and communities can keep them alive.”

It’s why Ryan and her classmates are determined to first acquire their ancestral language and then learn how to pass it on. It’s also why, until he retires in two years, Borserio will keep working through translations with his students for anyone who wants to have Haida in their publications. Because it extends the possibility that others will pick it up.

Nearing the end of the fishing charter business’s pamphlet that SHIP is translating, Borserio’s tongue slips.

“Tluu is?” he asks.

“Oh wait, I just said it,” he laughs. “My eyes saw ‘Canoe’ and I said it in Haida; that’s a good sign, eh?” Borserio maintains that he’s not a Haida expert, that he is only there to ask the right questions to the elders in order to bring out the stories and knowledge they hold. But if he doesn’t think of himself as fluent after 21 years of hearing the language spoken every day by practiced experts, then future students who just have recordings and books may take even longer to learn Xaayda kil.

A week after returning from a cultural exchange trip to Hawaii in May 2018, Harold Williams Sr. had pineapples on his mind. Cloaked in a rainforest that feeds plenty of bears, deer, root vegetables and wild greens, Haida Gwaii just doesn’t offer the same sweet flavours that bloom in the warmth of the tropics.

Every few years, Skidegate raises money to send their SHIP elders as ambassadors to visit other communities working on language revitalization, like Hawaii. Other years, a choppy eight-hour ferry ride across the Hecate Straight to cheer on the Skidegate Saints basketball teams at the All-Native tournament in Prince Rupert is enough of a thank you.

Flicking between pictures of chickens in the street and fruity drinks on his phone, Williams Sr. swipes to photos of the children that he and his SHIP classmates met at Hawaiian schools. There are 23 Hawaiian immersion schools on the islands. Students are educated in the Hawaiian language until grade five, when they begin to get their first instruction in English. It’s the ultimate goal for Haida language back home, says Joanne Yovanovich.

In Hawaii, the program follows a model similar to the 60-year-old French immersion curriculum in Canada. But where French is an international language spoken by millions, Hawaiian, Haida, Kwakwaka’wakw and the dozens of other Indigenous languages spoken across the continent have never been spread across oceans by people planting colonies. They do not necessarily have the protections afforded to European languages by dictionaries, vast catalogues of literature, film and recorded song, nor do they have official status. It is up to their knowledge holders to speak them to life on their own and commit themselves to transferring their languages to their descendants.

For some of the elders at SHIP, the closest they have come to graduating high school has been to watch the students whose classrooms they visit walk across the stage with button blankets instead of gowns, woven cedar hats instead of mortar boards and tassels. They’ve listened to valedictorians speak the words they helped save.

Looking back over 21 years, Borserio says that he had not realized just how much work the Skidegate elders had done, until he began the process of nominating the fluent speakers for honorary PhDs at Vancouver Island University in Nanaimo, B.C.

“When we did write it all down,” he says, “in terms of the work that we’ve done for museums around the world, translations in the community, the books we’ve done and the glossary, it was more impressive than I thought.”

The doctoral application to the university recently passed “seamlessly” through the approval boards at VIU, Borserio said. So on June 3, 2019, nine Skidegate Haida, or roughly 1.2 per cent of the community’s population, will be awarded PhDs from the university. The honours have been earned through 21 years of working on what Borserio calls the SHIP participants’ “magnum opus,” in time that ex-loggers and fisherman and shop owners and cannery workers invested into the life of their nation’s language.

SHIP’s fluent elders are surprised on March 15 with an announcement that they are to awarded honorary PhDs from the University of Vancouver Island.

Back row: Luu G̱aahlandaay Kevin Borserio, GwaaG̲anad Diane Brown, Niis Waan Harvey Williams, Jiixa Gladys Vandal.

Front row: Gaaying.uuhlas Roy Jones Sr., Yang K̲’aalas Grace Jones, SG̲aana Jaads K’yaa Ga X̲iigangs Golie Hans, Ildagwaay Bea Harley, Taalgyaa’adad Betty Richardson, and Sing.giduu Laura Jormanainan. [Photo © Haida Laas/Rhonda Lee McIsaac]

Living a language on screen:

SGaawaay K‘uuna Edge of the Knife

Harold Williams (left) plays Chinaay in SGaawaay K’uuna Edge of the Knife. [Photo courtesy of Niijang Xyaalas Productions © Isuma Distribution International]

In May 2018, Harold Williams Sr. boasted to SHIP visitors that he was going to be a movie star. The winter previous, he had gotten drenched in fog and rain on the north coast of Haida Gwaii near Masset, on-set of the first-ever fully Haida feature film.

Haida art sits behind glass in museums in Brooklyn, London, Chicago and elsewhere around the world. The precision of the culture’s argillite carvings and black and red paintings is revered and has become iconic of west coast First Nations art. But stuck in glass boxes, the totem poles and masks’ artistic voices are muffled. SGaawaay K’uuna Edge of the Knife was conceived as the antidote: to bring Haida language and culture to life on screen. The feature film was meant to be a work of living art, not necessarily intended for audiences the world, but rather to inspire the people whose story it reflected, the citizens of the Haida nation.

The idea for the movie was brought up at a community meeting in Skidegate in 2011, when it was proposed that a film be made to show students and the Haida nation that their language was not only preserved but alive as well. Though it was initially imagined as a documentary, artist and writer Gwaai Edenshaw pitched a tempting script to tell a traditional Haida legend that would ultimately be translated into Haida dialects, with contributions from SHIP. With the help of Isuma Productions, the studio of Inuit producer Zacharias Kunuk (who wrote and directed the award-winning 2001 film, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner), Edge of the Knife was launched.

Tyler York, a Haida carver from Skidegate, played the film’s protagonist. Just like every other cast member, he had no acting experience before filming began in 2017, and even less mastery of the language. So, just like the formative language boot camp in 1998, the cast’s first assignment was to attend a three-week language retreat, isolated at the north end of Haida Gwaii. There, they learned from the few fluent speakers of Masset and Skidegate dialects who were cast in the film. York himself nearly did double the work, he said at a 2018 screening at the Toronto International Film Festival, because he began learning the Skidegate dialect before realizing that his character was from the north and therefore would speak the Masset dialect instead.

Set in a fishing camp in 19th-century Haida Gwaii, the film follows Adiits’ii, a carefree young man who takes his best friend’s son out for a canoe trip against the warnings of village elders who predict that a wild storm will soon hit the camp. After the young boy drowns in the sea, Adiits’ii flees into the rainforest to escape the burden of guilt that he feels. There, he slips from his human-self to become a supernatural Wildman, the Gaagiid/Gaagiixiid (Masset/Skidegate dialects) of traditional Haida legend.

Erica Ryan played Adiits’ii’s mother in the movie. Beyond her few lines, the teacher-in-training took on a much larger role as a southern dialect specialist on set, coaching actors through their lines. In the film, the actors’ limited language ability punctuates the lack of background conversations in some scenes, like when the members of Adiits’ii’s village capture the Gaagiid/Gaagiixiid and attempt to exorcize the supernatural beast from their friend.

“It [was] a lot of pressure,” says the film’s co-director, Helen Haig-Brown. “[The actors would be] so focused on, ‘God let me remember my lines, god let me remember my lines,’ [and] ‘let my pronunciation be right.’” There were even times when Haig-Brown would have to remind the actors, in English, of what they were expressing through their newly learned language.

Sgaamsgid Harold Williams Sr. has a stack of autographed photos of himself in costume on the set of SGaawaay K‘uuna Edge of the Knife, so that he can hand them out to visitors. [Photo courtesy of Sgaamsgid Harold Williams Sr.]

Some of the actors, like Diane Brown and Harold Williams Sr., could improvise a few Haida lines in the background of some shots. But many of the ad libs in crowd scenes, like when the families have captured the Gaagiid/Gaagiixiid, were unusable in the final edit, says Haig-Brown. Not because it was poorly pronounced Haida, but because the nonnys (an Anglicism of the Haida word for “grandmothers”) would be asking each other when it was that they were supposed to say their lines or where they were supposed to move on set, all in Haida, just off topic.

When the viewer recognizes the unnatural gaps in chatter where extras in a Hollywood film might improvise lines, they are also reminded of what makes SGaawaay K’uuna so monumental in the first place. The film’s co-directors Haig-Brown and Edenshaw use the unpolished silences to draw a parallel story of the Haida Nation’s journey to reclaim their language and heal from the colonial precedent that led to its fragility.

Likewise, Adiits’ii struggles to overpower the Gaagiid/Gaagiixiid on his own. In a scene towards the end of the film, he twists and contorts his way between thick, spiky stalks of devil’s club. (York’s creature-like actions were coordinated by a movement coach who worked with Andy Serkis to create Gollum’s character in the Lord of the Rings films). He emerges, heaving with deep and pure breaths, his skin slashed and bloodied from the plant’s needles.

What may look to be an act of self-mutilation to a euro-centric audience is seen much differently through a Haida lens. It is an act of healing, say the directors — though perhaps extreme in its prescription; devil’s club has been traditionally used in various forms by Haida people for spiritual reasons and to treat burns, tuberculosis, fever and other ailments.

The film ends as Adiits’ii is being cut by Chinaay (“Grandfather”), played by Williams Sr., to exorcise the Gaagiid/Gaagiixiid. The young man, like the Haida language, is safe in his community but his outlook is uncertain; his past may yet impact the outcome of his future. Adiits’ii, like the language being revived by the Haida nation, lives on precariously, balancing on knife’s edge.

The film has helped to haul Haida language to international prominence as totem poles and masks did for the nation’s carving skills. It received coverage in The Guardian after its TIFF début and it won “Best Canadian Film” at the Vancouver International Film Festival last October. Even before the film was invited to TIFF, Ryan had a feeling she was part of something monumental.

“I remember sitting with Helen Haig-Brown on that final day and just being like, ‘Whoa, when this film goes to Toronto, I’m going,’ she recalls. “[Haig-Brown] just kind of laughed at me was like, ‘You know we need to be invited first, right?’

The movie has since been shown in Victoria, B.C., Ottawa, and elsewhere across the country, though the Haig-Brown maintained last August that the best screenings would be those in the community halls of Skidegate, Old Masset andKetchikan. In those spaces, like with the speeches of the 40 first immersion students in 1998, people heard the music of their language play loudly and with pride.

“’One day when Dempsey [Collinson] and I were talking on the radiophone in Haida,

a fisheries officer came on the phone. He said, ‘You guys quit speaking a foreign language on this fishing ground.’”

Collinson replied, “‘This is not a foreign language… English is foreign to us!’ No more noise after that.'”

– Gaayinguuhlas Roy Jones Sr. in That Which Makes us Haida

Last December, on the Friday before SHIP went on hiatus for the Christmas break, Borserio and his students invited friends and family to a private screening of the movie in the longhouse. Alone in the dark, Grace Jones sat beside a seat left empty for her husband. She had not come to class for several weeks.

The day before, the Monumental Pole in front of the Hospital in Queen Charlotte gleamed a fresh coppery orange, shining with the night’s frost in the morning sun, the open skies a relief after a week of behemoth winds and pelting rain. SHIP was running on a tight schedule: they had been invited as the guests of honour to the high school’s Christmas lunch, but on their way, they had an appointment to meet at the hospital.

The elders had driven the seven winding kilometres west of the longhouse in Skidegate to visit one of their own, Roy Jones Sr., who had been there for over a month, in a hospital room with a view of the fishing boats docked in Queen Charlotte’s harbour.

The hospital has been a popular field-trip destination for SHIP’s participants, who have repeatedly visited to see and to sing for past pillars of the classroom and protectors of their language, Xaayda kil.

SHIP’s participants have become such a staple at the hospital that the program’s crab crest now hangs in the building’s atrium, behind nurses who greet many of the participants as past patients. In May 2018, Grace Jones said she couldn’t count the number of times her husband had been to hospitals on Haida Gwaii, in Prince Rupert, or Vancouver.

“Losing Roy, we lose Grace, too,” says Borserio. The couple had always come to SHIP as a team, nearly two hundred years of knowledge, stories and respect, side by side.

The Jones didn’t always speak Haida as fluently as they do now, after having learned and taught at SHIP for over 20 years. Early on, the couple had to reach back into their childhoods to dig up the knowledge that Indian day school had tried its best to steal.

“At SHIP I learned to pray in Haida,” Jones Sr., who has been teaching the language since the 1980s, says in That Which Makes us Haida, a book of brief Q-and-A biographies of Haida language experts from Skidegate, Old Massett and Alaska.

Beyond teaching, the former fisherman has also used Xaayda kil to assert Haida control of the natural resources of his people’s territory. When he and Dempsey Collinson were out on the fishing grounds, they would use their language to keep their discoveries secret from other boats.

“One day when Dempsey and I were talking on the radiophone in Haida,” Jones Sr. recalls in That Which Makes us Haida, “a fisheries officer came on the phone. He said, ‘You guys quit speaking a foreign language on this fishing ground.’” Collinson replied, “‘This is not a foreign language… English is foreign to us!’ No more noise after that.” After all, he knew the waters well.

Borserio had struggled to control the distracted eyes and wandering attentions of his students in the days before their hospital visit, like any teacher would, right before a two-week break. A lot of class time was filled with Dii gwey (bingo), but even lotto scratchers, toques and flashlight prizes get boring after a while. In the interludes, he had turned SHIP into a choir to sing for Jones Sr.

Donning Santa hats, SHIP-issued jackets, and the men in their sharpest Haida or Christmas ties, Jones Sr.’s classmates welcome him and Grace into the hospital rec room with a Xaayda kíl rendition of “When the Elders go Marching in,” his favourite of SHIP’s song translations.

As he lifts his eyes to say “Haawa,” or “Thank you,” it’s easy to hear that Jones Sr.’s speech has slipped since the spring. This time, his papery vocal chords take a few sentences to vibrate to life. His voice sounds more like a raven’s now: soft and hollow, but still commanding.

Grace Jones, front left, and her husband Roy Jones Sr., behind her, are serenaded by their classmates from the Skidegate Haida Immersion Program in December 2018. Denver Cross, back left, waits to re-record Jones Sr.’s pronunciation of a letter. [Photo © Jensen Edwards]

Around him, a dozen powerful voices in various keys wash over the room with verses he helped translate. Nurses peek around the doorframe from the hallway, checking in on their regulars. “Sk’yuugaay gaadas kaadxa xidii,” the choir warns Jones. Sr. with high-pitched shouts. “Santa Claus is coming to town.”

“The War is Over,” “Amazing Grace,” “Silent Night,” and “Blue Christmas” make up the other songs on SHIP’s set list. The singers hardly pause between them, leaving little time for emotions to slip in.

The group keeps singing because, in the silences between songs, the tone falls on a minor chord. Everyone knows why they’re here. After Harold Williams Sr. croons out the final notes of Elvis’s “Blue Christmas” and Eddy Hans’s guitar strings stop vibrating, the room’s energy gets heavy again. Tears follow, Haawa’s and well wishes next. Borserio cuts through the seriousness with a joke about the men’s need for bigger paper clips in order to hit the high note at the end of the tune – “Xiidii!” (as in, “Santa Claus is coming to town!”). When it’s time to move on to lunch at the high school, to leave the Joneses behind at the hospital, the students and elders of SHIP line up to wish their classmates a merry Christmas. “Thank you, uncle, auntie.”

Last fall when Jones Sr. was still at SHIP translating house names, opining on fishing regulations and speaking his language into a microphone for his grandchildren to listen to, his vocal chords misfired. In the middle of a recording, he had pronounced the wrong K. It was unusable, said Golie Hans the day before SHIP’s Christmas hospital visit. In the pale green and white hospital room dressed in his SHIP jacket and tie, Borserio’s apprentice Denver Cross pushes against a tide of elders headed out the door. After all the others have said goodbye, Cross leans down to Jones Sr., sat in his wheelchair. An audio recorder anchored in his hand, he holds it up to capture the eldest male Xaayda kil speaker’s raspy loaded K.

**This text was completed in May 2018. Gaayinguuhlas Roy Jones Sr. rejoined his fellow doctors and classmates for the latter part of 2019. Jones Sr. died on May 27, 2020.

Below: Gaayinguuhlas Roy Jones Sr.’s jacket sits on his seat at SHIP, bottom left, in May 2018. [Photo © Jensen Edwards]