Back to hoofing it

This is a four-lane divided highway, but it’s also a de facto pedestrian corridor for people making their way back home to communities in northern Saskatchewan, and it’s a regular hitchhiking route for Bird, 48, and Paul, 28.

It’s also the Friday before the Labour Day weekend, a busy time for vacationers gassing up in Prince Albert and driving north to cabins at Waskesui Lake, to the golf course at Elk Ridge Resort, to their fishing boats on Lac La Ronge, or to a campsite at Beaver Glen. The line-up at a Petro-Canada with 14 pumps on the south side of town is three cars deep.

About 6,600 vehicles will drive this stretch of highway each day, according to Government of Saskatchewan statistics.

But without a car of their own, Bird and Paul must hitchhike to connect. They’re in a long-distance relationship, so it’s important for them to visit, but it’s an arduous trek every time. In the three years they’ve been together, they’ve seen each other about once every three months. Each time, either Bird or Paul needs to hitchhike, alone.

“It’s hard to see each other,” Bird said.

Leona Bird and Jordan Paul hitchhiking north on provincial Highway 2 from Prince Albert in August, 2018. [Photo © Lisa Johnson]

Montreal Lake Cree Nation would be about an hour’s drive from Prince Albert for Bird. Today it will take her four hours of walking, waiting and riding along to get home safely.

When the provincially-run Saskatchewan Transportation Company (STC) ran a route along this highway, Bird took the bus a couple of times a month from her home to One Arrow, where Paul lives, or to Prince Albert to visit her daughter and family.

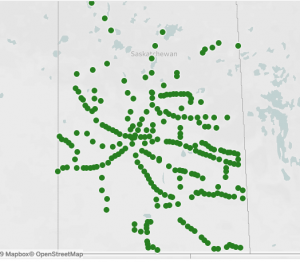

Bird may live in a relatively isolated place, but as a hitchhiker in Saskatchewan, she’s not alone. There are no bus routes connecting Montreal Lake to larger centres like Prince Albert. In fact, there are no bus routes connecting anywhere in Saskatchewan except for those running between large cities: Regina, Saskatoon, Prince Albert, North Battleford, Yorkton and Lloydminster. For many residents of remote communities across the province, hitchhiking – whether with a thumb out on the highway, or a post to a social media – is the only way to travel.

In some jurisdictions in North America and Britain, public transportation is falling victim to government austerity budgets, sometimes falling into the “death spiral” of underfunding, falling revenue from user fees, and further funding cuts.

In Western Canada, where populations in rural areas are dwindling and more people are relying on personal vehicles to get around, many rural bus routes are unsustainable without government support.

Saskatchewan has a population of just over 1 million people, almost 80 per cent of whom own a personal vehicle and are spread out over a geographic area bigger than California, so it’s impossible for private companies to provide bus service to every half-abandoned former railway outpost or remote reserve. There are ghost towns, sure, but small cities like Estevan, Swift Current and Moose Jaw have thriving populations – even if they ebb and rise with the price of potash, oil and coal. They are far from being ghost towns, and rely heavily on the highways that connect them to workers, health services, and higher education.

So, for 71 years, the Saskatchewan Transportation Company (STC), a Crown Corporation operated by the provincial government, ran routes around the province, whether ticket sales covered the cost or not. The STC connected more than 253 communities until its funding was cut from the provincial budget in 2017. The final day of service was May 31 of that year.

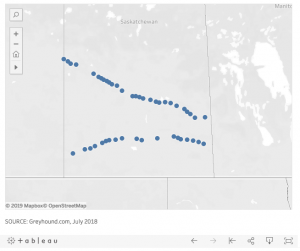

Greyhound Canada – a private company – wasn’t the only service left, but it covered the most ground on the prairies.

Then it announced in July 2018 that it would cancel all bus service in Western Canada, and its service ended on Oct. 31. In the space of just over a year, this double-whammy left small cities and big towns on their own.

Greyhound service connected Saskatchewan to major cities outside the province, bridging Winnipeg to both Calgary and Edmonton on the TransCanada and Yellowhead highways, but it barely scratched the geographical surface of the province. And, despite connecting Saskatchewan to major hubs outside of the province, Greyhound’s routes in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba had declined by 41 per cent since 2010 partly due to an increase in car ownership and low-cost airlines, according to the Greyhound announcement.

Greyhound buses connected to STC at main hubs, then STC connected smaller communities. The two companies didn’t compete.

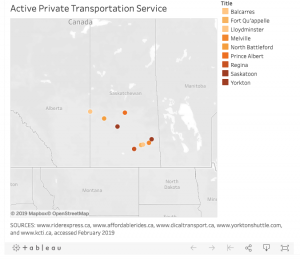

After most STC assets were auctioned off in 2017, 17 private bus lines applied for operating licenses. Since then, others have tried to take the wheel, but now only four operate: Rider Express, DiCal Transport, KCTI Travels, and the newest entry (the only one with wheelchair accessible vehicles), Affordable Rides. They connect Regina, Saskatoon and Prince Albert to Edmonton and Calgary. DiCal connects Yorkton to Regina.

So, you can rely on getting a regularly scheduled ride between those places, but almost nowhere else.

Most of the time, when Bird and Paul do catch a ride, it’s from somebody they know. That makes it easier to go south from Bird’s home reserve than it is to hitch a ride north. Most drivers are reluctant to pick up strangers, so she counts on someone recognizing her.

“Sometimes, you don’t even have a choice.”

– Leona Bird

To her, visiting family is important, and that makes hitching a ride a necessity. Bird is comfortably dressed and ready for what will become cool evening weather. And she doesn’t seem worried that they won’t get a ride.

She’s carrying a shoulder bag and wearing a toque and lightly-tinted sunglasses. She looks casual and self-assured. She can tell you how long it usually takes her to walk eight kilometres on the highway (about 2 hours), and she’s confident she can sense when a ride isn’t safe. But then again, it’s hard to tell.

Two weeks ago, Bird – who goes by another name on social media for privacy – was on her way to Montreal Lake. She caught a ride, then noticed the driver and passengers were drinking. The vehicle was taking an unconventional route, crisscrossing grid roads off the main highway. The driver’s swerving became dangerous, so she got out at a village called Northside, about a half hour into the ride.

Statistically, you’re more likely to encounter a drunk driver in Saskatchewan than in any other province.

There is also the danger of being struck by a vehicle when you are walking on the highway. According to the latest statistics compiled from police reports and insurance claims, two people between the ages of 45 and 64 years old were injured or killed while hitchhiking in 2017.

“Sometimes, you don’t even have a choice,” she said.

Bird’s experience isn’t unique, and it illustrates the fact that owning a vehicle can have a massive impact on your quality of life in Saskatchewan. Here, families having at least one is the statistical norm.

“We live in a very sparse and far-flung province, so many people are impacted by this loss of transportation,” said Jo-Anne Dusel, executive director of the Provincial Association of Transition Houses and Services of Saskatchewan (PATHS).

“This is an essential service for the province – and not just for women fleeing domestic violence, but people who are elderly, people on a low income, people with disabilities, and people who are not able to drive,” Dusel said.

The steady rise in automobile ownership rates was cited by the provincial government as a reason to cut off the STC, noting that increased vehicle ownership, moderate fuel prices, and increased migration to urban centres had led to a decline in intercity bus travel.

In 2016, STC reported that the low cost of fuel had made traveling by personal vehicle more affordable, and may have made STC fares appear more expensive by comparison. In 2017, the government announced that STC’s subsidy per passenger had grown from $25 per passenger 10 years before to $94 per passenger, since only two of the 27 routes in STC’s network were profitable – those running between Regina and Saskatoon and between Saskatoon and Prince Albert.

While most people in the province are able to drive, Prince Albert locals, like Jesse Henderson, 38, will tell you that there has always been a steady stream of hitchhikers along Highway 2, and that people would hitchhike no matter what kind of service a public bus company offered.

He rides a bicycle on the side of the same highway Bird and Paul walk regularly, just outside Prince Albert. He bought it for $5, and uses it to commute to work at a wood processor just outside the city.

When he heads farther north, he has a strategy: get to Spruce Home, about 20 km north of Prince Albert, where rides are more likely. Other people, he said, like to stop and wait under the highway sign just out of Prince Albert.

There’s never any shortage of people walking by the road or trying to flag down a ride, he said.

Jesse Henderson on the outskirts of Prince Albert, Sask. in August, 2018. [Photo © Lisa Johnson]

Vicky Dagneault sees the same phenomenon. She lives in Prince Albert, and often travels to La Ronge to see her mother.

“There’s always people hitchhiking to Montreal Lake,” she said. It’s so routine, she hardly thinks twice when she sees people hitchhiking this highway in the winter.

She said she’s picked up a hitchhiker, too. He was an elderly man hanging out at a rest-stop, looking for a way home. The casino, too is also a popular place to pick up rides.

“That’s what people do, they’ll go to certain places to pick up rides. And they’ll ask around or see someone they know,” Dagneault said.

“People are just used to it. Part of it is they’re desperate,” she said.

But the most visible are those who trudge across the bridge and start hitching from there, she says, referring to the Diefenbaker Bridge that crosses the North Saskatchewan River. The bridge is still technically within city limits, but once you cross it, it feels like you’ve stepped into the woods.

It might be mere coincidence, but if you find Highway 2 on Google Maps, zoom into Street View, and trace its path heading south towards the north end of the bridge, you’ll see two pedestrians at the edge of the highway. A man and a woman, their faces are blurred. It was taken after dark, timestamped the same month that Bird and Paul would have walked the exact same path.