Racing Through Their Veins: Doping in Horse RACING

Doping and legal medication keeps the horse racing industry divided. Photo courtesy of Ryan Haynes.By Raylene Lung

In March 2020, a thoroughbred horse named Maximum Security barrelled down the homestretch and crossed the finish line first at the inaugural Saudi Cup in Riyadh. He had just won the $10 million prize at the richest race in the world.

Everyone knew he was fast. He had previously won other expensive races, including the Kentucky Derby in 2019. But he just kept getting faster.

Then in that same year, his trainer, Jason Servis and 26 other trainers, veterinarians and drug distributors were charged for secretly doping several horses in a cheating scheme that shook the racing industry. Those involved customized and distributed mislabelled drugs so they could be secretly administered to the racehorses.

Servis is accused of administering performance-enhancing drugs to several horses under his control, including Maximum Security.

“It’s a good thing that happened,” says Reade Baker, a thoroughbred racehorse trainer in Toronto, Ont. “Hopefully, it’ll stop guys from doing stuff like that in the future.”

The events in the U.S. have caused the Canadian industry to question their own methods at the racetrack. Trainers, owners and industry professionals saw the Maximum Security scandal as a threat to the industry as a whole, and worried about their own hometown tracks. The controversy of doping and improper drug administration has been brewing in the American racehorse industry for decades, but the Canadian industry began to question if they had the resources to prevent doping from becoming a bigger problem behind their own barn doors.

They believe doping is a problem at their own racetracks. They believe people are getting away with pumping their horses full of performance enhancers. They believe drug testing is not effective or sensitive enough. Then there are controversial medications, the legal ones that are being abused. People in the industry say a lack of leadership and oversight and punishments have left the Canadian racing industry exposed to what could be a devastating drug scandal.

Drug scandals have happened on Canadian soil in the past. In 2007, Ben Wallace, a trainer out of Flamboro Downs in Hamilton, Ont., had a horse that tested positive for aminorex, which is an illegal stimulant. Wallace received about $15,000 in fines and a racing suspension in Ontario of up to five years. Then in 2010, at the Windsor Raceway, video evidence was discovered of trainer Derek Riesberry injecting a standardbred horse’s trachea with a hypodermic needle that forced officials at the track to pursue criminal charges. This case made it all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Horses race neck in neck at Century Mile racetrack in Edmonton, Alta. Photo courtesy of Julie Brewster.

the Recent American Scandals

On May 1, 2021, American trainer Bob Baffert’s face held a wide grin as his colt Medina Spirit bolted past the finish at the 147th Kentucky Derby at Churchill Downs. Everyone in Louisville seemed to have seen it coming — Baffert had seven Kentucky Derby winners. No one was surprised.

Then a few days later, Baffert’s three-year-old thoroughbred failed his drug test, testing positive for the steroid and anti-inflammatory known as betamethasone. The colt had nearly double the legal limit of betamethasone in his system.

Baffert has since been suspended from training at Churchill Downs. He had to wait for Medina Spirit to have a second test before the horse could be disqualified, but it was determined that the horse was treated with a dermatitis ointment containing the steroid prior to the race. Any trace amounts, no matter the source, are still illegal on race day in Kentucky. As of May 2021, Baffert was allowed to enter the horse in the Preakness Stakes in Baltimore, under strict testing and monitoring rules, despite Medina Spirit’s positive test results. Baffert was not allowed to attend.

There has been controversy around the case of Baffert’s horse’s positive test, including other trainers that say testing is too sensitive and the steroids didn’t aid the horse in his win. Others say he was getting away unscathed.

Then, on July 14, 2021, Baffert won his appeal in a New York courtroom, with the New York Racing Association nullifying his suspension at Belmont, Aqueduct and Saratoga racetracks.

Medina Spirit’s victory is still undetermined. The Kentucky Horse Racing Commission has yet to conduct a hearing; a date hasn’t been announced.

Only one Kentucky Derby winner has ever been disqualified because of a drug violation — a horse named Dancer’s Image in 1968.

But this isn’t the first time Baffert has been caught in an illegal drug scandal.

At the 2018 Santa Anita Derby, Triple Crown winner Justify tested positive for scopolamine, a nausea medication, the results were attributed to the natural jimson weed in the feed and bedding from Baffert’s barn.

Then in spring 2020, two of Baffert’s horses, Charlatan and Gamine, both tested positive for lidocaine after the Arkansas Derby. Baffert was fined and suspended but won his appeal after claiming that the medication in the horse’s system had been transferred through a pain patch that had been worn by his assistant trainer, Jimmy Barnes.

Later in 2020, at the Kentucky Oaks, Gamine tested positive again, for betamethasone. The medication needs to be administered two weeks before the horse races and was not, therefore showing up in the filly’s system.

Since the Medina Spirit scandal, the American and Canadian have been more alert to how prominent doping really is.

An exercise rider prepares to race a horse on the track in the morning at Santa Anita Park in Arcadia, CA. Photo courtesy of Julie Brewster.

An Inside Look

For an American industry with earnings in the millions, it is not surprising that trainers like Baffert and owners might do whatever it takes to win. But in Canada, which operates with slightly smaller purses, doping is still sneaking in behind stall doors.

There are currently only 12 Thoroughbred racetracks across Canada, some of which also host harness racing. There are 31 race tracks in the country that host both thoroughbred racing and standardbred harness racing.

According to a study conducted in 2010 by Equine Canada, the Canadian horse racing industry contributes $19.6 billion to the economy annually. Horse racing accounts for 29% of the revenue of the Canadian horse industry. Ontario has the largest industry, representing 26% of the total expenditures for the Canadian horse industry.

Jim Lawson, CEO of the Woodbine Entertainment Group, along with Christina Litz, the vice president, say the horse racing industry contributes more than 50,000 jobs. In Ontario alone, it accounts for 35,000 jobs and contributes around $2 billion to the national economy, through ticket sales and wagering. These jobs are possible, thanks to wagering on horse races through the pari-mutuel system in place, regulated and supervised by the federal agency operating under Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada called the Canadian Pari-Mutuel Agency (CPMA) since 2006. The agency ensures that pari-mutuel betting is conducted in a way that’s fair to the public.

The CPMA deters the use of illegal substances in horses through the Equine Drug Control Program, which monitors drug and medication use and controls every aspect of drug testing in the Canadian horse racing industry.

Doping is an issue but the administration of any medication at any racetrack in Canada (and North America) must be done by a licensed veterinarian. A vet has the authority to administer any necessary injectable medication, whether with a needle or syringe. In the case of oral medication, trainers are allowed to administer that themselves but it must be under the supervision of a vet. The rules around this can vary slightly among each provincial racing commission, but for the most part are the same. By putting the control of the drugs into the hands of the vets, this should theoretically defer illegal drugs from ever entering a horse’s system.

Steve Smith, who’s been a racetrack vet in Edmonton for over a decade and currently works at the Century Mile track, is familiar with the Drug Control Program. He says while trainers can’t administer anything (without supervision), they are able to request medications like hyaluronic acid (which aids in cell production) for the horse’s joint health. As it’s a natural component of healthy joint fluid, Smith says he has no problem fulfilling the trainer’s request for it if he sees fit.

“It would be totally common for a trainer to request something like that. And I have no problem, administering that to a horse,” he says.

A racehorse trots out on the track, ready to race, alongside a track pony at Northlands Park in Edmonton, Alta. Photo courtesy of Julie Brewster.

Let’s Talk About Drugs

Whether the drugs are administered safely by a vet or not, The CPMA Equine Drug Control Program is meant to keep track of whatever enters the horse’s system. The program was established to deter the uncontrolled use of drugs, both legal and illegal, in racehorses. Representatives of the program insist that positive tests are rare.

The program works closely with provincial commissions, such as Ontario Racing and the Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario to support the integrity of betting to ensure that all horses are raced fairly.

The program has guidelines that set out the dosage regimen for each classification of drug, including the time it takes for the drug to be completely flushed from the horse’s system. They test for all types of drugs as well, not just the illegal ones.

Provincial governing bodies determine the finish order of the race and can then determine which horse is tested based on performance or request. The Equine Drug Control Program collects and analyzes blood or urine from horses before or after a race. Positive tests are reported to the appropriate provincial regulatory body or racing commission to determine the penalty, if there is one, and how and when the drug was administered. They relay this information to the drug program, if they ask for it. The CPMA’s authority is restricted to post-race testing of races. According to the CPMA, there are two official laboratories that conduct the testing — the CPMA Reference and Research laboratory and Bureau Veritas Laboratories.

Out of competition testing (testing done before a race or on days outside of race day) is performed by provincial racing commissions.

The drugs are divided by classification, according to the Association of Racing Commissioners International, and the province investigates, and determines the penalty based on their findings.

All positive test results are made available to the public through each provincial commission. In the case of racing in Ontario, positive test data for the last 3 years is available on the Alcohol and Gaming Commission’s website but doesn’t offer enough information to be truly illuminating.

But James Watson, media relations for Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, says that the testing is thorough. He also says there are usually four types of positive tests. But Carolyn Cooper, a Canadian Pari-Mutuel Agency expert, says that the drugs aren’t always easy to identify.

“The issue is that a drug can fit into more than one category,” Cooper says.

Smith agrees, saying that there are some doping agents out there that aren’t detectable by the time the horse races.

Not only that, but some trainers and owners buy substances from outside of Canada that the CPMA cannot test for. Sometimes, they even have their own chemists creating compounds for them, says Dale Saunders, who has been a horse trainer in Alberta for more than 50 years.

While the actual tests are complicated, most testing is done after the races rather than before and only those who are assumed to have drugs in their system are tested. Cooper says taking a sample before a race is disruptive.

“Sometimes it can take an hour or two to get a urine test,” she says. “If the province wanted to pull a blood sample before a race, they could set the horse off. The horses know what their jobs are.”

Data suggests that the CPMA collects positive drug tests every race season. Infographic made with Piktochart. Photo credit to Woodbine Entertainment Group.

For example, drugs like aminorex act as a stimulant and are still detected in drug tests at the racetrack. But its testing is made difficult due to the fact that it is also a metabolite of a legitimate substance, according to the Kentucky Equine Drug Research Council. Another problem lies in how the drugs enter the horse’s system in the first place.

Morphine, on the other hand, while not illegal, is a painkiller and can enter the horse’s bloodstream via injection or pills. But both Watson and Cooper say that sometimes indirect exposure can also occur, for example, through a human’s prescription medication (as was the case with Bob Baffert’s Medina Spirit and the pain patch). Cooper says that often occurs when a trainer or groom urinates in a horse’s stall, which she says is not uncommon.

“The trainers are definitely more aware, and they’re taking a lot more care,” Cooper says. “But there are definitely still a few every year.”

Morphine can linger in the horse’s system for a longer period of time, even when administered legally. Sue Leslie, who has been president of the Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association in Ontario for 16 years, says this can occur when a horse undergoes a legal procedure and is given morphine by a vet. If the horse races a week or so later, the horse tests positive for morphine.

She adds that those aren’t the types of positives that concern her, considering how minute the amount of morphine is.

Another issue that arises are synthetic versions of illegal drugs that circulate. They are also hard to test for, and Smith says the solution is more out of competition testing — testing not done on race day.

“I think that would improve the integrity of racing,” he says.

Out of competition testing would help combat another major drug issue in the industry — blood doping.

The most common drug for blood doping is erythropoietin, or EPO. Produced naturally in the body by the kidneys, it signals the bone marrow to create more red blood cells, therefore allowing for increased oxygen carriage. Forms of synthetic EPO like epogen can be given to people who are anemic, but when given to healthy individuals, it can increase endurance, bringing the red blood cells to higher levels. When administered to horses, it similarly boosts their body’s production of their RBCs, enhancing their race performance.

EPO has been a longstanding issue in horse racing, Smith says, and has posed many issues in terms of testing, mainly because the synthetic drug disappears from the horse’s system quickly.

“EPO or derivatives of it, synthetic EPO, those sorts of things would be something that certainly can improve performance,” he says. “It is something that you need to do out of competition testing to really catch.”

While the drug disappears from the horse’s system within approximately three days, the effects can last up to a week — the horse may not receive a positive test, but they would have more red blood cells in their system.

“[Your horse] would be able to run not faster, but further. And that’s what racing is all about,” Dr. Rod Cundy says. “It’s not so much speed, it’s endurance.”

Cundy was a racetrack veterinarian out of Edmonton and Calgary for 40 years before joining the Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association of Alberta, the governing body for individuals in the racing industry. He has been involved with several racing bodies, advocating for different rules around drugs at the track.

He also says out of competition testing would solve this issue.

While out of competition testing does occur, it is not conducted by the CPMA, says Lydia Brooks, a manager of research for the CPMA. They are restricted to post-race testing of pari-mutuel races. Any other testing is performed by the appropriate provincial racing commissions.

Despite this, Cundy believes that not enough of this testing is done and says that regulatory racing bodies don’t do it often enough.

As a Horse Racing Hall of Fame trainer, Baker agrees.

“It’d be nice if they all tested before they race and they could run those tests but money is the object,” he says.

In contrast, provincial commissions like in Alberta and Ontario, have out of competition programs in place. Both commissions may order for a sample of blood, hair, saliva and urine at any time or place and without prior notice. The sample must be taken by a vet designated by the appropriate provincial permission to determine if the horse has any substance in its system.

If an owner or trainer doesn’t make their horse available for a test, their horse may be scratched for its next race, or the owner or trainer may be barred from entering any horse in future races in said province. In Ontario, the owner or trainer may also be subject to a monetary fine or suspension. The rules don’t outline the value or time period for either of these sanctions.

Another drug that has stirred up controversy is clenbuterol, or Ventipulmin, a bronchodilator that opens up a horse’s airways. Not only does it make it easier to breathe, it also has an acute side effect: it helps build up muscle mass. Horse trainers started using it after other anabolic steroids like testosterone became illegal.

“When they put a stop to [anabolic steroids], and were testing for it, [trainers] started using this clenbuterol to build up muscle mass on their horses and take advantage. That was a legal drug that was getting used illegally,” Cundy says.

According to the current CPMA guidelines, the legal dosage of clenbuterol (used as a decongestant) is 0.40 mg taken by mouth, twice a day for five days. It has to be out of the horse’s system within 28 days, but Cundy says he used to argue for the CPMA to increase the time.

“They had withdrawal time for that of only two or three days or something. And that’s not going to stop them from using it for this muscle building purpose. Eventually it got to seven days, but now they’ve got a ban on it in some of these jurisdictions in the U.S., it’s not allowed anywhere in their system ever.”

“That was one drug that I fought for big-time at the end of my career,” he continues.

Despite having initial pushback from the Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association in Ontario, Cundy says it was “10 years before they finally got on the bandwagon.”

Another doping agent that has been a hot topic at the racetrack is sodium bicarbonate or “soda doping”. Baking soda, which is alkaline, offsets the acidic lactic acid in a horse’s body, making their muscles less tired. The solution, often referred to as a “milkshake”, acts as a performance enhancer by boosting horse’s endurance. The process entails inserting a tube up the horse’s nose and down its throat, pumping a diluted mixture of sodium bicarbonate into its stomach.

“It’s still to this day one of the most abused substances in races, because you can tweak around the edges and give a horse so much and get away with it,” Cundy says.

He says there was only one time he can recall giving a horse baking soda, to a horse trained by straight-laced, Albertan trainer Rod Haynes. The horse went on to win.

However, recent research published in the Journal of Equine Veterinary Science reveals that soda doping doesn’t in fact boost horses’ performance. Soda doping in human athletes has been studied for years, but has often produced uncertain results. The data from the study concludes that from eight experimental trials of 74 horses, the sodium bicarbonate did not improve horses’ running abilities, in the simulated racing trials or treadmill tests.

Cundy says that testing has soda doping mostly under control now. For every horse that is taken to the test barn after a race in Canada, blood samples are drawn to determine sodium bicarbonate levels. Yet certain trainers, he says, still give their horses enough where it doesn’t go over the limit, yet still gives the horse an edge.

A jockey hugs his mount’s neck after a win at the Century Mile track in Edmonton, Alta. Photo courtesy of Julie Brewster.

A Furlong To Run: The Issue With Therapeutic Medication

Despite the strict testing, therapeutic drugs are allowed to be used by participants to treat daily ailments of their horses, according to Dr. Adam Chambers, the senior manager of Veterinary Services for the Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario. The CPMA has guidelines set out for these medications, limiting the amount and time window before a race.

These therapeutic drugs can often be a point of contention, says Dr. Steve Smith, who’s been a racetrack veterinarian for 16 years and currently works at the Century Mile Racetrack in Edmonton, Alta.

“I think some people do perceive it as doping,” Smith says. “For one thing, they get this medication on race day, it is the actual only legal race day medication.”

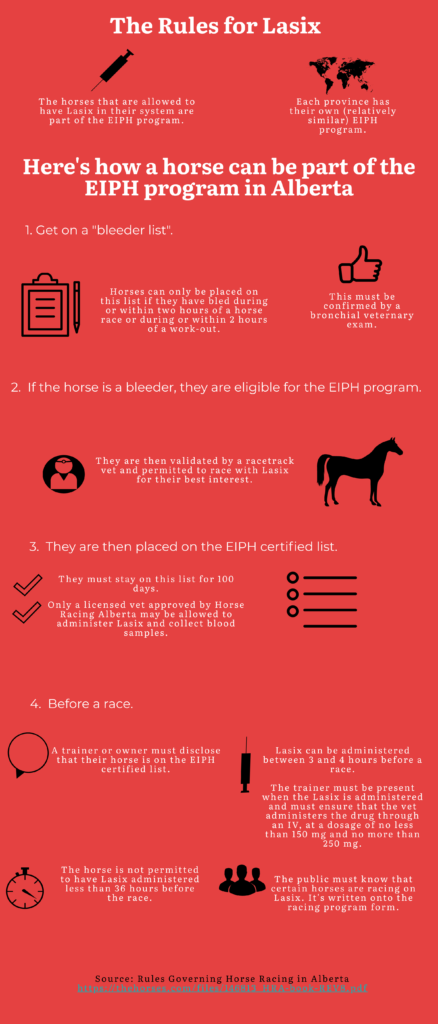

Lasix, an anti-bleeding and diuretic medication known as furosemide, is under the most intense scrutiny. While legal and administered to prevent respiratory bleeding, excess fluids and EIPH (exercise-induced pulmonary hemorrhage) from running at high speeds, Lasix can mask the effects of other drugs and can act as a performance enhancer by dropping the horse’s body weight on race day.

Sue Leslie, the current president of the Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association of Ontario, says the organization works closely with the CPMA to ensure the proper usage of therapeutic drugs, like Lasix. She says this race day medication is an effective way of helping horse’s cope humanely and run to their full potential.

“We’ve seen time and time and time again, because of the amount of pressure on the horse racing, that they do bleed,” Leslie says. “Whether it’s heritage, it’s genes, the weather, the small factors that contribute to that, and we have…what our board considers to be a safe way of helping horses to cope with that.”

Leslie says that there are people who overuse Lasix but she believes it’s a low percentage. Despite its abuse, she says she still believes there is a place for it.

“It’s part of being an athlete, I guess you want to be proactive and prevent things like [bleeding] from happening. I don’t think it’s for regular use,” she says.

The strict dose and a four- hour window (plus or minus 15 minutes) before the race means that Lasix must be administered intravenously. If not, the horse cannot race. And if the horse is supposed to be on Lasix, and the test comes up negative, the owners of that horse will be penalized. Lasix is likely the most closely monitored drugs at the track, yet issues still arise around its use.

Rules surrounding Lasix in the Canadian industry, specifically Alberta. Sourced from Rules Governing Horse Racing in Alberta. Infographic made with Piktochart.

Lasix is the most popular medication in the industry that teeters between being therapeutic and contributing to doping issues. Cundy, grew up in the 1970’s, a time when Lasix was used to give horses an edge. But over time, he began to notice the way the medication drained minerals from the horse’s body, causing them to need excessive fluids after.

The retired racetrack veterinarian has now been “fighting tooth and nail” to have Lasix removed from race day.

“I think Lasix is abused, right from the get-go in horse racing,” he says. “I think you’d be better off without Lasix, period.”

Saunders, as a veteran trainer, also agrees that there is no place for race day medication.

But as always, Lasix remains a point of contention.

Steve Smith, a track veterinarian, says he believes if a horse bleeds severely, giving it Lasix becomes a welfare issue. However, he says that if horses raced without Lasix, they certainly can again.

“We definitely raced through 150 years before we had Lasix. But on the other hand, I definitely understand the perspective that it has safe, relatively minimal side effects. It does prevent an issue.”

Leslie, the president of the Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association of Ontario, says that while some believe it to be a performance enhancer, it is only due to the horse not choking on blood.

“Our experience at HBPA is that the only thing it enhances is it allows the horse to breathe properly so it can run its best,” she says. “If you’ve had a horse running three or four times and it’s been bleeding, then you put it on Lasix, and suddenly it runs faster than it ever has before.”

Julie Brewster, who works for Horse Racing Alberta, the racing commission in the province, says Lasix has been in the industry for nearly 25 years and a longstanding argument among horsemen and women.

“Some say, I don’t think we should use it,” she says. “And they say, ‘but if you don’t give it to them, you’re being crueler to the horse’… by not allowing them to race [with it]. So they say it’s a fine line.”

Smith suggests there is evidence to suggest that horses bleed more than they used to. This begs the question of whether or not horses that shouldn’t be racing are becoming reliant on Lasix so they can race.

Jerry Robertson, a horse trainer in Alberta, agrees with Smith, saying that some trainers can overuse Lasix, but that the enhancing effects are not an issue by race time, given the CPMA guidelines.

“I don’t like to see a horse that bursts a blood vessel in their lungs and is gushing blood,” she says. I don’t think it’s for regular use… it dehydrates your horse, and it’s not good for them. But for race day medication, I think there is a place for it.”

Cundy is on the opposite side of the Lasix debate — it’s something he fought for in the last decade of his career at the racetrack. Lasix can be administered right up to six hours before they run.

“I finally said we should go to a policy of no race day medication, which they have in some jurisdictions in North America,” he says. “There’s no need to give horses any kind of drug on race day. There’s nothing therapeutic that they need in order to survive or to run.”

Lasix is the one medication that remains at the forefront of the doping debate. Even if it is a therapeutic medication, the abuse suggests tighter regulation is needed or it risks become another drug that whose performance-enhancing outweighs its health benefits.

A thoroughbred filly gets a kiss on the nose at Highfield Stock Farm in Aldersyde, Alta. Photo courtesy of Julie Brewster.

Testing, Testing

In 2019, the CPMA analyzed 25,851 samples collected from racehorses, and issued 28 positive analyses. This equates to a positivity rate of about 1/10 of one per cent, or approximately one positive test for every 1000 samples tested.

Despite the seemingly detailed process of the testing, trainers like Baker have complained that the testing is flawed and not strict enough.

“We need a leader, an American leader and a Canadian leader, to lead our sport and to be able to have the funding to do the proper testing or investigation,” he says. “Whatever it might be, we’re not getting that.”

One issue, as previously mentioned, is drug retention. Saunders, a trainer, says this has been an issue with certain drugs and medications. They can last longer in a horse’s system than expected. For example, penicillin should ideally be out of the horse’s body after 18 days or so but can often remain in their bodies for up to 30 days. The dosage and time it was administered can be legal according to the guidelines but because of this retention, the outcome of testing ends up being skewed.

Oftentimes, however, trainers overstep the legally allowed time for a drug to be administered (which is laid out in the CPMA’s elimination guidelines). Whether or not it was retained, they still took the risk in the first place.

Robertson, who’s also a trainer, says testing helps prevent horse people from abusing race day medication like Lasix. She says the testing is careful enough that no one can get away with overusing it but still questions the system as a whole.

“Sometimes you wonder if horses are all being tested, or all the tests are being sent in but I don’t know,” she says. “There have been an abundance of bad tests here in the last few years.”

On the flip side, some trainers and owners say testing is too rigorous and too sensitive, with horses testing positive for trace amounts of therapeutic medications. Leslie says the tests are picking up pain aids like bute, which don’t offer any racing advantage.

This can end up being a catch-22, in that it causes some trainers to get bad reputations via positive tests.

“That can put a stigma on racing that it doesn’t deserve, when they start giving positive tests on these drugs that really aren’t affecting the performance,” Cundy says.

Leslie, as the HBPA of Ontario president, says the CPMA needs to adjust its testing to determine what actually affects the horse.

“I think a lot more work needs to be done….to be a lot more sure about what really is affecting a horse’s performance,” she says. “Because our standards are pretty tight on illegal drugs.”

Leslie says she also believes testing is not adequate enough to determine certain levels of therapeutic medications. The trainers, for the most part, know what is legal and what isn’t.

“There isn’t enough money in the industry to do adequate testing, to determine what the appropriate levels are for certain therapeutic drugs,” she says. “And I think in terms of illegal drugs, in some cases, there’s no testing at all. Because they don’t even know some of the things exist and [don’t] learn how to test for them.”

And the testing disparity goes beyond that as well, she says.

“I think there are different chemicals, drugs that are very, very difficult for the CPMA to test for. I believe that those types of drugs are harmful to the horses, and have absolutely no therapeutic benefit to them whatsoever.”

“Administering those types of drugs should face extremely severe penalties right up to being banned from racing,” she continues. “For example, a drug that might freeze a joint so that the horse doesn’t feel pain, that is totally unacceptable. Our industry does not tolerate that nor do we want it. That is completely different from giving a horse some bute because they’ve got a muscle pull. There’s a big, big difference.”

As a trainer, Robertson says she wonders if all the horses are being tested, or if all the tests are being sent to be analyzed.

Trainers in the industry, like Saunders, believe that the penalties for positive tests (which vary according to each provincial racing commission) are not deterring offenders from doping. Especially when some trainers have drug chemists working for them, producing drug concoctions on the side, he says.

“I think stiffer fines and longer penalties would help quite a bit,” he continues. “There’s so much money now and so much desire to be on top or win.”

But even so, if penalties are to be harsher, they need to be executed accordingly, which as Cundy, a vet, says, it isn’t always the case.

“In Alberta, the punishments are big enough if they catch people, maybe too big for some of these innocent drug violations. You can get caught up in that and be out of a job for six months, because you had an innocent, bad test. Whereas, these big trainers that are using blood doping or [sodium] bicarbonate and things like that, are getting away with it. All they do is get fines and short suspensions that don’t really deter them.”

“If the trainers or the owners or whoever don’t get punished, they’re just going to keep doing it,” Saunders, a horse trainer, says.

When comparing Canada to the U.S., it’s difficult to determine who’s handling doping sanctions better, since they are monitored differently.

“Maybe more in the States, there seems to be some guys that are repeat offenders, and they don’t seem to be getting suspended or getting the appropriate penalties,” Robertson, a trainer in Alberta, says. “But I think they probably are here.”

While doping in Canada is federally monitored, in the U.S., each state has its own jurisdictionary rules — they may get away with one drug in Kentucky but not in California for example as the rules can change as soon as a horse crosses state lines.

In this regard, industry individuals can be criminally charged for more “minor” doping and drug offences, because they are contravening state legislatures. In Canada, because of the CPMA, everything is regulated across all provinces and territories, and sanctioning falls under individual racing jurisdictions.

No matter the case, Canadian horsemen and women still believe there needs to be heavy editing done to both testing and sanctioning.

Baker says ultimately the problem lies in the resources — the security personnel don’t have the training or manpower or funding, he says, to monitor those who dare break the rules.

But as a Horse Racing Hall of Fame trainer, he says the reason people get away with doping so much is because the industry doesn’t want to invest in catching them.

“There’s the crux of the problem,” he says. “There’s not enough security to do anything, to catch anybody.”

For those that don’t play the game right, the penalties aren’t strict enough, he argues. He says that wrongdoers need more than a 60-day suspension that mimics a paid holiday.

He says racetracks are not going to put out a whole lot of money to investigate someone who’s entering horses and filling the races. He insists that racetracks want clean sport but it isn’t to their advantage to eliminate people who do wrong.

This double-edged sword may be one of the reasons why racetracks don’t take more action when it comes to medication abuse of the horses. Or perhaps another reason that regulation is weak is the burning desire to win.

“There’s nobody to watch the people,” Baker says. “Those silly rules are hurting the guys that are trying to play the game right.”

HBPA president Leslie agrees.

“If I give a horse cocaine today, it shouldn’t matter if it is negligible. It’s against the law for me to give the horse cocaine, it’s not a therapeutic drug. And therefore that person needs to be extremely heavily penalised. There’s no place for it in our sport,” she says.

Three bay thoroughbreds stretch across the finish at Century Downs racetrack in Calgary, Alta. Photo courtesy of Julie Brewster.

All About Money

Doping also drastically affects the fairness of betting in the racing industry. And one way to see how it affects wagers is through trainer percentages.

Percentages are determined by how many races a trainer has won. Cundy says that the percentage is a strong identifier in determining if someone is cheating or not. You have trainers who are consistently at the top because of their good horses and can often sit around 25 win percentage. But some trainers go from having 15 per cent to 35 per cent in a single racing season and Cundy says that raises suspicions, and in turn, is bad for the industry.

“They destroy racing by winning so much. Other people in the business don’t want to run against them,” the veterinarian says. “You gotta bet they’ve got some edge and you gotta bet it’s something drug-related.”

“Racing is all about money,” Cundy continues. “If you can’t pay the bills, or your horses aren’t making enough money, you’re out of business.”

“There’s so much money involved in these races now that guys will overstep the bounds of the goodness of the horse, just to get a name, a picture, and to make a lot of money,” Saunders, an Albertan trainer, says.

While betting on doped horses can cause money upset from outside the barn, there’s also a costly situation inside the barn. Cundy also says that 90 per cent of drug use in racing is supplements, vitamins and the like, to make a horse feel better. He says they just abuse the owner’s checkbook rather than the horse.

“Those are drugs that don’t really affect the horse and the outcome of the race, they just run up the vet bill,” he says.

As a vet, he says he lived “quite comfortably” selling medications to owners and trainers that were for the most part useless. And, he says, 70 per cent of the vet bill was from race day medication.

“I would tell my clients, ‘Hey, I don’t believe in these drugs.’. But everyone else is getting them, so I better have it…”

It wasn’t always this way, he adds. When he worked at the track in the 1970’s and 1980’s, he says he aimed to keep his clients’ vet bills low. Any bills that were on the more expensive end were always for horses that had health problems. Nowadays, he says that’s not the case.

“You go to places like Woodbine racetrack [in Toronto], and the vet bill can be more than the training bill, because of all the different drugs that they think they need or that they think help them….Whichever came first, the vets pushing the drugs or the trainers desiring the drugs, but caught in the middle of this is the owner who doesn’t really need the vet bills.”

Having more therapeutic drugs make their way into the horse’s bodies posed an interesting trajectory for Cundy.

“I used to be a master of what I call the “negative sell” in terms of giving horses drugs before they run, just simple things like B12, and anti-inflammatories, very innocent drugs,” he says. “So I used to tell my clients, I do not believe in most of these drugs, but I own a couple of horses and when my horses run, I give it to them. Because you’re dealing in a business where inches make 10s of 1000s of dollars difference.”

Smith, as a vet as well, believes that sometimes trainers and owners invest in medication for their horses because of the cost of other aspects of racing. He says as a vet, he understands trainers’ reasoning for spending money on medications.

“You put an incredible amount of work and resources into it. Quite literally 10s or hundreds of 1000s of dollars that you’ve spent on the purchase and preparation of the horse, months and months and months of time, then you get the horse to the races and it has an episode of bleeding. Once it does bleed, they are prone to having that happen again. From a trainer’s perspective, I think they would rather just prevent it in the first place and then it’s probably better for the horses’ career.”

The stakes of racing have ultimately changed and Saunders is well aware of it. As a trainer, he watches the stakes grow higher and higher in the racing world in Canada.

“I guess there’s too much money. It’s not just the friendly hometown crowds that you’re running for,” he says.

The stakes are arguably much higher now. According to the Equine Canada study, approximately $312 million was paid out in purses in 2010, and $1.45 billion was wagered on horse racing in Canada in that same year ($1.04 billion was wagered in Ontario). This includes both thoroughbred and standardbred racing.

The funding model for horse racing differs provincially but each one receives a significant part of revenue from wagering. Some provinces receive some fundings from slots on racetracks.

In terms of betting, Rande Sawchuk, the director of policy and planning for the CPMA, says it is hard to determine how much doping impacts it directly.

In turn, the newly-passed Bill C-218 doesn’t address doping or match fixing directly, Sawchuk says. Provinces in Canada already conduct betting on multiple events without the code specifically addressing the issues of doping or cheating.

An exercise rider poses with a young racehorse in the barn at Northlands Park in Edmonton, Alta. Photo courtesy of Julie Brewster.

The Good Old Days

The horse racing industry looks quite different than it did 50, 30 even ten years ago. Saunders, who has been a trainer in the industry for over 50 years, says the industry focused more on horsemanship back then. He says he misses when he first started training in 1969, when racing was seemingly an entirely different sport.

“People don’t work horses and look after horses the same,” he says. “They use more medications.”

He says people used to believe drugs were on the up and up several years ago. But Saunders says he thinks horses are running better than they did before illegal drugs came to the track, but not to their benefit.

“There’s too many things that come out nowadays that affect the performances,” he says. “They shouldn’t be running as [well] as they do.”

Cundy, who practiced veterinary medicine from the 1970’s until 2010, says he grew up in an era where drugs at the track weren’t that common either. Perhaps anabolic steroids like testosterone made its rounds for building muscle mass or vitamin B12 for increasing a horse’s red blood cell production but there was nothing “exotic”, he says.

“I’ve watched it evolve over the years.”

And it has. Now, drugs operate differently in the racing world than before. And industry leaders say that a lack of leadership and oversight and punishments that are far too light mean the next massive drug scandal could happen in America’s northern neighbour’s stables.

“We need a leader, an American leader and a Canadian leader, to lead our sport and to be able to have the funding to do the proper testing or investigation,” Baker, a trainer. says. “Whatever it might be, we’re not getting that.”

A trainer pets a horse after a win at Century Mile racetrack in Edmonton, Alta. Photo courtesy of Julie Brewster.

her organIs This Age-Old Industry At Risk?

Ultimately, doping not only harms the horses but also the industry.

While there are many drugs that are acceptable for medical reasons, trainers like Saunders say there are too many performance enhancers that cause too many ups and downs.

Particularly, Saunders says, drugs are hurting the horses in the long run.

“You’ve got horses performing one day and not performing the next day… you use these drugs all the time and you eventually wreck a horse,” the thoroughbred trainer says.

Saunders says having horses rely on the aid of drugs longterm does everything but benefit the animal — trainers and owners bring their horses along too fast, affecting their longevity.

“It makes them perform better than the horse actually is. And they’re putting drugs into them now that develop horses away too fast,” he says. “[The horses] aren’t coming around and developing in structure themselves. Like steroids, clenbuterol that makes your horse grow up faster, bigger, and they can only perform so long on it, instead of being a regular horse and developing themselves.”

Saunders says back when he was in the middle of his training career, horses could make 125 starts in their life, but now making 15 is considered monumental. When he first started out his career at the track, he learned how to work on a horse, rubbing its legs with liniment and letting it wade in the river to ice its limbs. Now he says trainers and owners turn to bute to ease horse’s pain, a band-aid solution that he says eventually takes its toll.

Cundy, too, grew up in an industry that seemingly had its differences. While he understood the need for excessive use of medication as a vet, he says he believes there should be a lot less circulating in racing barns.

“It’s a tough battle,” he says. “Because the people that really want to keep the drugs going [at] the racetrack…are the trainers and the vets. Trainers seem to think they need drugs to train and vets love selling them.”

In terms of doping, veterinarians like Smith and Cundy believe there’s a misconception when it comes to the term “drugs”, and that all things administered to a horse can’t be lumped into one category.

“[Horse people] are damaging their own sport because people are going to have a perception of drugs,” Cundy says. “For the most part racing is on the up and up, but…those few drugs that are getting abused give it a bad name and make people say ‘I don’t want to be involved in this.’”

Julie Brewster says her organization, Horse Racing Alberta, is trying to combat some of the perception that every racehorse is on drugs.

“People think that just because we use the word ‘drug’ that means it’s illegal, despite the fact that horses can race on limited amounts of medications,” she says. “For us, it’s just a lot of trying to be transparent as much as we can.”

“It’s an uphill battle,” Cundy says. “Trying to get drugs out of racing is really as good as the resistance from the people. Like I said, [people in the industry] are only shooting themselves in the foot and the industry itself.”

Smith also says that there is an important distinction to make between a positive test for illegal drugs and legal medication.

“I think it does often get mixed up in the public perception because people don’t necessarily have the background to make that distinction,” he says. “If a horse gets a positive test for legal medication, the way it gets reported in the media, I think people perceive it as horse doping when it really probably wasn’t bad.”

While some trainers and vets think doping is prevalent and threatening the industry, others say it isn’t a current issue.

“There’s a public perception that there’s a lot of things out there that can actually improve horses’ performance,” Smith says. “There [aren’t] a lot of illegal drugs that aren’t easily detected that can make a horse run faster.”

“I don’t see it myself,” Robertson, a trainer from Alberta, adds. “Not recently, anyway. Probably not in the last five to 10 years. We suspect it but there is nothing to prove it.”

Cundy says that most people do want to play by the rules.

“I think most trainers want to do it the right way. They want to compete on a level playing field, but they’re not. They’re competing against people that are not playing by the rules, or they’re beating the rules.”

Smith says that in his 16 years of veterinary practice at the track, he has never been asked to administer anything illegal, nor has it ever been in his possession. But he says he knows the industry isn’t entirely clean.

“I’m not naive to suggest that it doesn’t happen. There are trainers that are maybe overly reliant on legal medication, or use it to truly dope a horse,” Smith says.

He also says the doping regulation is more under control in Canada than in the U.S.— he says one of their main issues is their lack of an all-encompassing regulatory body like the CPMA. But in any competitive environment, there are always stakes.

“People’s livelihoods are at stake and money is to be made,” Smith says. “There’s an incentive for some people to cheat, but it’s a pretty regulated sport.”

Trainers that end up doing too well shouldn’t always be accused of cheating either, he says. Some trainers can do well for a long time in the sport but because of the nature of the environment, toxic words can spread.

On the other hand, he says if one horse can’t seem to run well with anyone but a single trainer, he becomes suspicious.

“That’s always kind of a red flag for me.”

He also says the situation is a little different in the U.S., with trainers and owners travelling from state to state where rules may contrast.

“It probably is a little bit more common [there],” he says. “They maybe do slip through the cracks a little bit, going from one place to the next.”

An organization based in the U.S. called Water Hay Oats Alliance, or WHOA, advocates for clean racing in the country and is firmly against the use of drugs in the sport. They are the most notable in rallying for tighter regulation amongst the states, including negotiating the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act into law in December 2020.

While some industry people in Canada still say the regulation is not enough to eliminate doping altogether, individuals like Leslie at the HBPA in Ontario say their racing is clean for the most part.

“I personally know pretty much most of the trainers at our two thoroughbred tracks. And I believe our racing is probably 97 per cent clean,” she says. “The amount of oversight now, even amongst horsemen, amongst themselves. They’re heavily monitored by [Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario], by the race track security, by [their] own neighbor. As a trainer, it’s very difficult to hide if you’re doing things that are illegal.”

She says, like Smith, she is also not so naive.

“I’m not saying there’s zero scoundrels. I know scoundrels exist in every business.”

Baker, whose training is based out of Woodbine but has trained all across Canada and has also served on the HBPA in the past, says that most individuals in the industry want to race the right way, do right by their animals and would never risk that over a doping syringe.

“They’d rather have the horse eat than they would eat,” he says. “They can’t take a chance and lose all that for one positive test on some drug they don’t know anything about.”

A chestnut thoroughbred gallops towards the finish at Century Mile Racetrack in Edmonton, Alta. Photo courtesy of Julie Brewster.

The Home Stretch: Looking Ahead

As it stands, the horse racing industry in Canada is urging for more careful measures to be taken around doping, before a Bob Baffert or Jason Servis type make their way into a Canadian track. Veterinarians and trainers alike want less medication being pumped into horses’ veins, tougher sanctions on those who dope and a longer and healthier racing career for the animals.

As a longtime trainer, Saunders stands by his solution — cut race day medication and make penalties stiffer on those who abuse the system.

Ten day suspensions aren’t enough for trainers whose horses can still run, he says. If they were suspended for two years, he says they would be a lot more careful with what they do.

Saunders says while careful testing and slightly more intense penalties seems to be deterring industry people, the reliance on therapeutic medications can keep a horse from healing. And that adds another layer of complexity to the doping debate.

Cundy, who was a track vet for 40 years, says horses are better off without many of the drugs and medications that circulate . He says if horses are to run for longer and run better, performance enhancers and therapeutics that act as crutches need to be eliminated.

“Back in the olden days, there weren’t a lot of drugs,” he says. “Horses would run 15, 20 times a year and now they’re lucky to run five or six times a year.”

Not only that, but he says vet bills are pricier than ever. This poses a risk to the industry, driving owners out of business when keeping a horse becomes unaffordable.

The continued use of drugs aren’t going to benefit the horse, or the horsemen and women.

“If you have a fast horse, that’s the best thing you can do to win a race,” Roberston, a thoroughbred trainer, says. “I’m a horse lover and horse care is my number one objective. I would never give anything to harm a horse, but you want them to feel their best going into a race. So anything you can do for them as far as their health goes? I think that’s the biggest thing. Any drug is not going to be the answer, not in the long term anyway.”

Welfare of the horse is undeniably important to most people, and the few bad ones in the industry harm the reputation of the good ones.

“By far, trainers and owners are honest, they love their horses,” HBPA president Sue Leslie says. “And none of them would do anything that they thought was putting a horse at risk. And it’s a shame that this handful of people who don’t want to abide by the rules are tainting all the good people that want to do right by their horses. And I think it’s important that the public understand that.”

She says the industry has to continue to work to catch perpetrators that aren’t abiding by the rules, despite the fact that they’re largely a minority.

Baker, as a trainer who has been in the horse racing industry for more than 40 years, insists more needs to be done. While more and more doping is tested and exposed, more and more offenders will hopefully get caught.

“A lot of people will say this is good for the industry, and in some ways it is,” he says. “But then there’s other guys saying this is the tip of the iceberg.”

While there are still those who say that racehorse doping is on the decline, recent events in the U.S. suggest otherwise. Whether trainers and owners see it with their own eyes or not, the Canadian industry is at risk of following in the hoof prints of its southern sister.

Testing needs to be stricter, penalties need to be harsher, drug limits need to be reevaluated. Trainers, owners and people in the industry alike will continue to advocate for more regulation of doping, as they should. Medication abuse, whether legal or illegal, has the potential to further harm an already hurting industry, and the horses that make it.