The museum in a wheat field

The town, whose population fell from its peak of 350 in the 1920s to only two in the late 1990s, is in immaculate condition. And that’s because the last two people living there, Keith and Beverly Hagen, have devoted much of their time to preserving its legacy.

Remaining debris from old buildings could also turn into a fire hazard or a home for rodents, Beverly said.

The general store is now a museum to Scotsguard’s history. Hundreds of artifacts have been collected over the years with a connection to the town. On one shelf there are pencils and postcards imprinted with the name of the town. The old Coca-Cola-branded chalkboard still marked with prices of food from the curling club hangs in another corner, right next to the old black-and-grey striped baseball uniform for the Scotsguard team.

As Keith tours around the countertops and antiques in the old store, he has an anecdote for everything, as any good museum curator would.

Pausing to look at it, Keith laughed.

“It almost looks like they should have been in jail, but that’s what they had,” he chuckled.

And in a picture frame near the back is a beautifully printed list of names of the men and women who proved their farming claims and business ownership when the list was made in 1915.

But despite all their hard work, neither Keith nor Beverly thinks the town has much time left.

Scotsguard is about 250 kilometres southwest of Regina and about 20 kilometers west of Crichton, where Aime Lacelle is the last man remaining. The two towns are connected by Highway 13, which forms part of the Red Coat Trail, named for the route taken by the North-West Mounted Police in 1874 to establish law and order in Western Canada. But in Saskatchewan it’s also known by a more ominous name: the Ghost Town Trail.

Empty highway

“A lot of those communities, especially in the southwest corner (of the province) were ghost towns because they should never have been there in the first place … other than that the Dominion Lands Act had scattered the population,” economics professor Rose Olfert said.

The Dominion Lands Act was a federal law enacted in 1872 to give land rights to new immigrants. According to the Canadian Encyclopedia, around 625,000 such sections were given to homesteaders. Clifford Sifton, Minister of the Interior from 1896 to 1905, wanted settlers with farming backgrounds to be able to work the land and withstand the harsh weather.

What the Dominion Lands Act did not do, Olfert said, was divide land based on its quality. Southwestern Saskatchewan, in the area called the Palliser Triangle, is dry and arid and unsuitable for sustained crop farming.

“Certainly by the 1930s during the Depression, it was clear that there was no way they could farm there,” Olfert said.

And as farmers left – not all at once, but over many years – fewer towns were needed.

“Whatever was there by way of a town to service that population … had no reason to exist anymore,” she added. “Their raison d’etre was gone.”

Keith and Beverly Hagen say they don’t often think about why Scotsguard dwindled to where it is now, and they don’t like to think too far ahead either.

“I don’t think we can alter the future,” Keith said.

“I don’t think we can alter the future.”

Although Scotsguard was not the biggest centre for the nearby communities (with the larger towns of Admiral and Shaunavon close by), the Hagans describe it as an exciting place. Keith recalled a time when there were six grain elevators in the town and a small hotel to service the nearby settlements. And Beverly said she fondly remembered coming into Stella’s Café in the evenings because it was the only place nearby that was open past nine.

“When you look at the monument … it’ll tell you Scotsguard’s nickname was ‘Little Chicago’ because there were several bootleggers and poker dens around here,” Keith said.

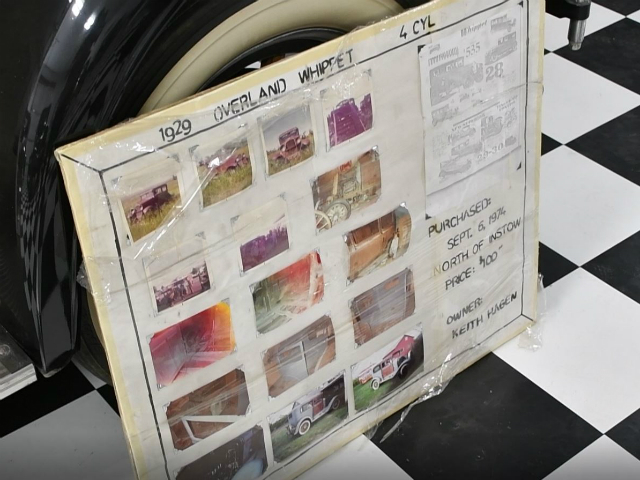

The Hagens’ passion project has touched members of the nearby community. In 2016, Scotsguard celebrated its 100th birthday with a party held on the property. And Keith hosts an annual car show to show off some of his vintage automobiles. He said the most recent show attracted nearly 400 people.

“She just flipped out,” he said. “Her daughter said she’s still talking about that.”

More than finding historical connections, it’s a gratitude to the Hagens for preserving this history that they find the most rewarding. The Hagens also tend to the nearby cemetery, and visitors will often express their gratitude for taking care of what’s left.

“We’re just going to have to leave it in somebody else’s hands,” Beverly said.

“Fortunately, Bev and I are [in] relatively good health… but if someone is having some serious health issues you don’t have an hour to get to the closest place,” Keith said. “I think that’s the biggest determining factor in a lot of these things.”