Part I: Colombo

The Galle Face Hotel is a remnant of Sri Lanka’s colonial period. (Photo © Stephen Cook)

On my first night in the five-million person metropolis of Colombo, the largest city in Sri Lanka, I stayed at the world-famous Galle Face Hotel because in its location and presentation, the colonial structure has been party to the history and division that has shaped this island nation.

Directly south of the Presidential Secretariat, where men in military uniforms stand guard with AKMs in hand, the hotel runs along the Galle Face Centre Road and beside the Galle Face Green, a strip of green park alongside the ocean that often hosts families, night markets, and kites. Sometimes it hosts political rallies – one in only a week’s time, according to posters, relating to the then-ongoing constitutional crisis triggered by the president’s illegal sacking of the prime minister.

The Galle Face Hotel sits on the coast as it has done for more than 100 years. It was once known and continues to bill itself as the “best hotel East of the Suez,” famous enough to be featured a national stamp in 2012. It is at once past, present and future: the history of this island nation can be read in the contours of its grand renaissance architecture, a repeating row of columns in beige with red tiled roof, while from a wicker chair on the front veranda one can see the future sprouting in concrete and steel.

The hotel boasts a long list of luminaries who have graced its finely-carpeted halls: Richard Nixon, Indira Gandhi, Emperor Hirohito, Lester Pearson. Prince Phillip, while stationed on the island during the Second World War, supposedly spent time here – his car is still on display in the second-floor museum among other memorabilia. Arthur C. Clarke, who lived on the island much of his life, supposedly wrote the final chapter of 3001: The Final Odyssey here.

But while Clarke may have been looking to the future, Galle Face is firmly rooted in the past. Watercolour paintings of village life are set alongside Victorian furniture in its hallways, recalling the building’s past as a Dutch villa and then hotel opened by four British entrepreneurs in 1894.

Sri Lanka, with thousands of years of written history, survived three successive colonial regimes. The Portuguese destroyed ancient temples in their religious fervor while the Dutch built forts in coastal towns to protect their economic interests.

And finally the British Empire, which burned brighter, hotter, and more painfully than its continental predecessors. The masterwork of William Manning, Governor of Ceylon in the early 20th-century, was to foster division in cementing colonial domination. Minorities were favoured in administrative positions, alienating the majority Sinhalese Buddhist population.

Early on, the British administration defined those divisions when it established a national legislative council along ethnic lines in 1833, creating ethno-political rivals jockeying for influence in the colonial framework: Sinhalese versus Tamils versus Moors versus Burghers.

Those divisions continued to simmer long after the British left in 1948

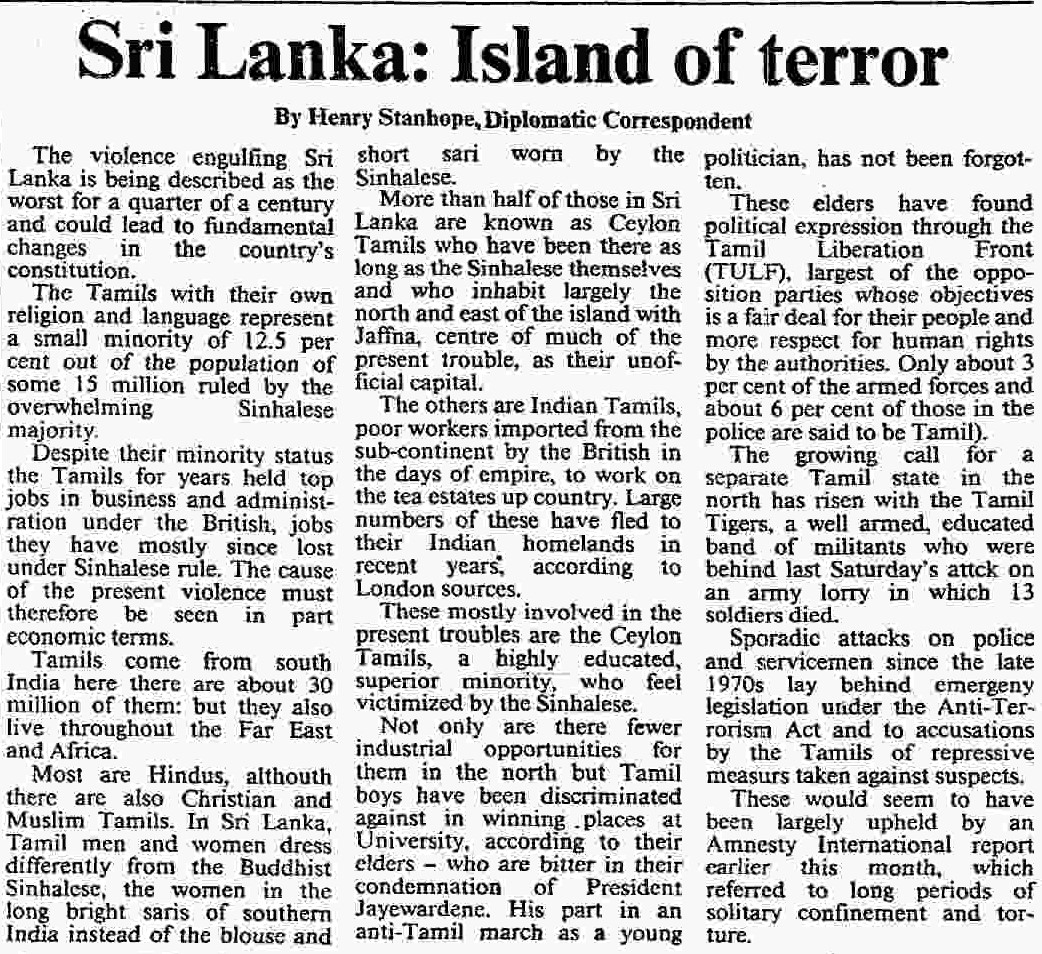

A clipping from the Times of London dated Jul. 28, 1983 describes the turmoil in Sri Lanka.

THE WAR BEGINS

“Despite their minority status the Tamils for years held top jobs in business and administration under the British, jobs they have mostly since lost under Sinhalese rule,” reads an article from Jul. 28, 1983 in The Times of London.

“The cause of the present violence must therefore be seen in part economic terms.”

It was Black July. Its spark was the killing of 13 soldiers in an ambush by the fledgling LTTE, still in the early stages of its fight for a separate Tamil state.

In the days that followed, as many as 3,000 Tamils were killed as pogroms spread throughout the country. Sinhalese mobs roamed the streets of Colombo destroying and burning Tamil businesses and homes.

Rolling clouds of smoke would have passed over the red-tiled roof of the Galle Face Hotel.

Black July was only the beginning of 26 years of bloodshed, crashing in successive waves of violence amid calmer tides of ceasefire. When it ended in March 2009 in Mullaitivu, 350 km northeast of Colombo, Tamil civilians were caught in the crossfire.

But journalists, foreign and domestic, were kept away in keeping with a generally repressive media environment.

The government crafted its own narrative, retold in state-owned outlets and on the plaques of monuments.

On Galle Face Green, a hundred-metre tall flagpole hosts the state’s lion-adorned flag in a monument to victory that makes no mention of its toll on civilians. At its base, the dedication commends the sacrifice of brave Sri Lankan soldiers during “humanitarian operations.”

Major construction projects line Galle Face Road, some employing foreign Chinese workers. (Photo © Stephen Cook)

In the decade since, foreign investment and workers have flooded into the country, sometimes worryingly derided as a competition for geopolitical influence by China and India through loans and agreements.

Along the Galle Face Centre road, where British gentlemen and ladies once ‘took in the air’ during the Victorian era, trucks of Chinese construction workers compete with electric cars and auto rickshaws in near-constant bumper-to-bumper traffic. The skeletons of skyscrapers haunt the skyline and, from the beachside, rows of red cranes are visible across the inlet. That distant 266-hectare strip of land is set to one day become the Colombo International Financial City, a massive port and financial district.

The Galle Face Hotel is a nostalgic sight here, its squat structure overshadowed by nearby hotel complexes like the Taj Samudra or the Shangri-La. The governmental Sri Lankan Tourism Development Authority, which drives the development of tourism throughout the country, is only a few scant blocks away.

The government has directed policy heavily in favour of tourism, much of it in the Sinhalese-dominated south, since the end of the war even as the economies of the pluralistic east and Tamil-dominated north flounder.

Nonetheless, tourism has been an overall success for Sri Lanka. According to a report by the World Travel & Tourism Council, tourism in Sri Lanka accounted for more than a tenth of the GDP in 2017 and 11 per cent of total employment. In 2010, international hospitality consultancy firm HVS reported a GDP contribution of only 0.6 per cent.

Since then, revenue from tourism has only increased year to year.

This year Sri Lanka was named Lonely Planet’s destination of the year.

“It’s something that’s been happening since pretty much the end of the war,” says Mario Arulthas, advocacy director for the international non-profit People for Equality and Relief in Lanka. The New York Times listed Sri Lanka as one of the 31 places to visit in 2010, prematurely declaring that the conflict’s end had ushered “in a more peaceful era for this teardrop-shaped island off India’s coast, rich in natural beauty and cultural splendors.”

Arulthas calls this tourist narrative short-sighted and that it is “not very responsible that publications can continue to show just one side of what’s going on” without addressing oppression in Sri Lanka. The Sri Lanka of travel catalogues and guidebooks is sterile smiles and sites, rarely acknowledging the pervasive presence of the war in peacetime.

Nor do they acknowledge the island’s pluralism – the Air Canada magazine I read on my flight to England features an article selling the authentic charms and Buddhist philosophy of a trip through the southern provinces. Meanwhile, state-owned Sri Lanka Airlines uses “ayubowan” in its advertising, a Sinhalese greeting wishing long life.

While Sri Lanka is a parliamentary democracy, the politics of the national government heavily favour the dominant Sinhalese population in what critics call an “ethnocracy.” Buddhist nationalism is also a potent force – and one that has repeatedly supported wartime president and strongman Mahinda Rajapaksa – that sees Sri Lanka as a nation solely for Sinhalese Buddhists.

But this power imbalance plays out in other very real ways. As a special rapporteur reported to the UN in 2017, there is an ongoing stigma against Tamils and the hallways of power – government, judicial, and security – are all Sinhala-dominated.

“Failure to address these issues promptly and effectively will provide fertile ground for those intent on resorting to political violence, as real and perceived grievances are exploited by militants to garner support among vulnerable and alienated sections of the population,” reads the report.

“The price that future generations in Sri Lanka will have to pay for the continuation of this legal repression may prove as costly, or even costlier, than that which has so far confronted the present generation.”

There have also been two recent UN resolutions – one in 2015 and one in 2018 – calling on the government to pursue transitional justice and reconciliation.

None of this is immediately apparent for visitors stopping over at the Galle Face Hotel, likely before moving further south to lusher and less urban destinations.

But my next move was to travel east, to see the Sri Lanka that had suffered checkpoints, bombings, bloodshed and massacres, to move beyond the romanticized past of Ceylon or the future promised by massive construction projects visible from the hotel veranda.

I wanted to see the reality of the present.