When European settlers first discovered the lake region of Muskoka, it seemed like the “wilderness,” the “true north.” But Andrew Watson, a doctoral student in history at York University who has researched the environmental history of Muskoka, says that describing Muskoka as at one time “wilderness” is a very European way of looking at it.

Lake Muskoka in 1872 was considered wilderness, at least to European settlers.

Sketch by George Harlow White, photo courtesy of the Toronto Public Library Digital Archives

“There were always people in Muskoka,” he says, referring to the aboriginal tribes of the Algonquin, Ojibwa, and Cree that would migrate to lakeside camps during the summer from their more permanent inland settlements. “Many First Nations people continued to go (to the lakes) every year, even through European settlement and as tourism grew.”

But European settlement truly began in the 1860s and 1870s, particularly with the introduction of the Free Grant and Homestead Act of 1868 by the Ontario Government. The Act allowed for anyone to receive 100 acres of land (200 if they had children under the age of 18), so long as they settled there and cleared at least 15 acres of land in five years in order to grow crops.

It sounded like a pretty good deal to many families, who came in droves to settle the “North”.

Alf Mortimer’s family was one of them.

Alf Mortimer and his grandfather, Alfred Mortimer, on Dec. 29, 1923. Alf’s grandfather migrated to Muskoka after receiving a land grant from the Ontario government.

Photo courtesy of Alf Mortimer

“My grandfather was given a land grant in Ontario and that’s where they started to live—Mortimer’s point,” he says, referring to the acres of land his family received on Lake Muskoka. A smaller portion of this land still goes by his family’s name. “Their grant covered a tremendous amount of property, from Port Carling to Bala, that end of the lake.”

“They arrived from Hamilton. That’s where they landed from England and then they came up by oxen to Gravenhurst and wiggled their way up here to this place.”

But families like Mortimer’s quickly realized they would have to find another way to provide a livelihood, as farming atop the Canadian Shield proved to be a disaster.

“The intention was for Muskoka to be a place of agriculture like southern Ontario,” Watson says. “Being on the Shield, agriculture was almost a complete failure.”

Some people turned to logging, though there was mainly only one type of tree in Muskoka that had any commercial value—the white pine.

“That’s why you don’t see many white pines today,” Watson says.

But it didn’t matter. For as if by some divine intervention, a new industry opened up to Muskoka, one with a world of possibility for this place of such natural beauty—tourism.

City folk from Toronto, Hamilton, and parts of the United States were beginning to venture north, looking to “get into wilderness” or “back to nature.” At first, it was mainly men who came up to hunt and fish, but soon they were returning with their wives and children.

“The intention was for Muskoka to be a place of agriculture like southern Ontario… Being on the Shield, agriculture was almost a complete failure.”

“Settlers in Muskoka started to realize the economic potential of these people coming from outside Muskoka, just wanting to visit,” Watson says. “They’d show up, looking for a place to sleep for a night and maybe have a meal, or maybe take some provisions with them to go camping.”

“Settlers in Muskoka latched onto this. They started to realign their household economies, particularly the ones that were next to the water, towards providing the services and goods that these new, ‘prototourists’ were looking for.”

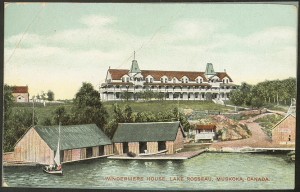

The first resorts in Muskoka were born out of farms, as settlers took visitors in and turned their homes into family-run wilderness lodges. Because it was nearly impossible to ship perishable items to Muskoka at this time, settlers were able to sell the little food they could grow at an incredible mark-up, using that money to expand their boarding houses into hotels, and some even into resorts. Some of the most iconic and beloved Muskoka resorts—Cleveland’s House, Windermere House, Elgin House, Paignton House—began as just that, houses.

Windermere House, here pictured in 1910, is one of the few historical resorts still in existence in Muskoka. Like many others, it began as a farm.

Photo courtesy of Toronto Public Library Digital Archives

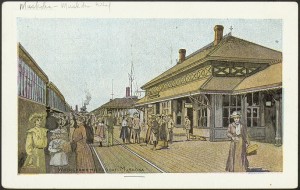

And popular they were, though they attracted a certain kind. Even though some boarding houses were quite cheap, it was the cost of actually getting to Muskoka that established the clientele of the Muskoka tourism industry as the upper middle class. Voyagers had to take a railway train to Gravenhurst, the community that has been labeled the “Gateway to Muskoka” since it sits at the foot of Lake Muskoka. From there, tourists would board a steamship, perhaps the Sagamo or the Segwun, which would then drop them off at the various hotels.

Through the success of these boarding houses-turned-hotels came another breed of hotels. The Muskoka Lakes Navigation Company, which owned the steamships, noted the true potential of tourism in Muskoka and thus built the Royal Muskoka Hotel in 1901, by far the most luxurious of them all at that time. Several other entrepreneurs decided to do the same.

And the industry boomed. By the end of the 1890s, there were 34 hotels in Muskoka. By 1903, there were 57. By 1909, 76.

Tourism was not only the heart of the local economy, but also the determining factor of how the community developed.

“The hotels became important hubs,” Watson says. “Steamers stopped at these places, and over time cottages started to pop up near these hotels.”

Liz Lundell, a historian, explains it further: “People who came up to then spend a few days at these resort properties decided they’d like their own lakeside properties and decided to build their own cottages.”

Around Cleveland’s House sprang up the community of Minett; around Windermere came a village of the same name. These communities became where locals and new cottagers alike could come to get fresh produce and pick up their mail. The tourism industry didn’t expand Muskoka—it built Muskoka.

But while the number of cottages in Muskoka was beginning to grow—between 1885 and 1915 there were 300 new cottages built—the resort industry was still the beating heart of the economy of Muskoka well into the 20th century.

“The hotels became important hubs.”

“At any one time, (the resorts could) hold 5,000 people,” Watson says. “When they were full they represented a large chunk of people, pretty close to the same number of cottagers. Back then, resorts were as important if not more important to the local economy than cottagers were.”

With World War I, tourism in Muskoka declined slightly, and did so again more pronouncedly during the Great Depression and into World War II. But the post-war economic boom re-charged tourism in the region once again, this time opening it up to more people, particularly those of a lower class, who now had better wages, the eight-hour work day, and the five-day work week, and not only could afford to drive a car north but also had time to spend leisurely.

Vacationers coming to Muskoka travelled by train to Gravenhurst, and then boarded a steamship at the Muskoka Wharf.

Valentine & Sons’ Publishing Co. Ltd, 1910, photo courtesy of Toronto Public Library Digital Archives

But something else happened as well—cottaging.

“The comparison between tourism post-war and pre-war is entirely different,” Watson says. “The whole economic model for resort tourism is really undermined by cottaging.”

“Cottaging really does come in and steal the show. It becomes affordable to cottage.”

James Bartleman, the former Lieutenant Governor of Ontario who was born to a native mother and raised in Muskoka, describes the new mix of classes in Muskoka during this post-war era in his memoir, Raisin Wine.

He writes in the third person: “With arms outstretched in the manner of Superman, he flew past the site of the deserted Indian settlement of Obajewanung, past the modest cottages of the less affluent summer residents, past the trailer camps, cabins, and campgrounds that in season were always jammed to overflowing with working-class families, past the elegant summer homes of the rich people from the big city, located a discreet distance from their poorer neighbours…”

For the locals, everything was about catering to the summer vacationers who invaded the region from June to August.

“Cottaging really does come in and steal the show. It becomes affordable to cottage.”

Mortimer’s family never tried to open a resort, but their life’s work was dedicated to resort-goers and cottagers, first in the form of a supply boat, and then in the form of marinas.

“My grandfather, Alfred Mortimer, built two steamships here at Mortimer’s point in the early 1900s,” he recalls. “One was called the Rosseau, and one was called Florence Main after my grandmother.”

“They ran a service from Bala to Port Carling to Beaumaris to Gravenhurst and Bracebridge up the river, delivering the mail and so on,” he says. “That was when the (Muskoka Navigation Company) first started with their boats. Eventually they took over because they were a big company. There were a dozen boats they had at one point.”

Visually see where the “big three lakes” – Joseph, Rosseau, and of course, Muskoka – are located as well as the many communities, resorts, and special characteristics that dot the lakes.

View The Places of Muskoka in a larger map

“My father, Eddie Mortimer, had a boat delivery and marina service out on Lake Muskoka,” he says. “That’s where I grew up and that’s where I learned all about boats and engines. That’s when I was doing the deliveries and things. I ran that for maybe five or six years when I was about 10 years old. I’d pick up all the freight in Bala off the CP railroad and take it to cottages all through Bala to Beaumaris up the Port Carling River. Eaton’s and Simpsons supplied most of the food—canned goods and non-perishables—they supplied that to the lakes. It was all shipped in to Bala. I’d fill a boatload and I’d go as far as I could until I got it all emptied and then I had to go back. It was a daily thing. That was how people got their food in here, anything that wasn’t locally grown, that is.”

In 2012, the Port Sandfield Marina, owned by Alf Mortimer (left), celebrated 60 years of business. Mortimer’s grandson, Jonathan Blair (right), now operates it.

Photo courtesy of Alf Mortimer

In 1952, Mortimer opened his own marina in Port Sandfield, the point where Lake Joseph and Lake Rosseau meet. He says when he first bought the land, the area, which at one point had had an old hotel (Prospect House, which burned down in 1916), was virtually empty, save for several nearby resorts. As cottages began to pop up, however, Mortimer’s business grew, since people now had boats they needed to get serviced.

But that’s not to say that the resort industry died post-war. Quite the contrary. In 1957, there were 554 resorts across Muskoka, from the most opulent to the most modest, all of them filled up each summer with repeat guests. Just as Muskoka was open to anyone to settle there in the 1860s, post-war Muskoka welcomed tourists of every kind. If you wanted to own land, you could. Any type of hotel you wanted was available. And just as the lakeshore filled up with cottages, resort rooms filled up with tourists.

But today, all that has changed. For starters, the affordability that cottaging in Muskoka once offered for middle-class families in the post-war era is long gone.

“It’s not affordable anymore,” Watson says. “It’s changed again. It’s for the rather wealthy to cottage nowadays.”

But instead of people turning to Muskoka resorts, they are turning away from Muskoka. By 1991, there were only 126 resorts left in the District of Muskoka. Today, there are 111, and with those, the average occupancy rate is 45 per cent. Even in the summer peak of July and August, resorts in Muskoka are only 67 per cent full.

Tourism, once the beating heart of the Muskoka economy, has declined, and with it the heart of what Muskoka truly is.