Food insecurity

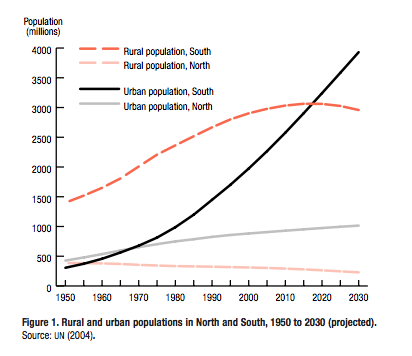

Credit: Graph taken from Growing Better Cities. [Original Data Source: United Nations World urbanization prospects: the 2003 revised population database.]

Busy cars pass through a Kibera’s busy road on the southwestern edge.

“Ninety per cent of the community lives below the poverty line and only receive one meal a day,” says Naimo Abdullai, whose organization, Savo Foundation, is located in Makina ward.

In October 2014, Savo started its sack gardens. Since then, the organization has used the food to provide a subsidized school lunch program for children in the neighbourhood. While it’s not much, it does help in a small way.

“We started the farm so our family would have something at the end of the day,” says Naimo. “Once the seedlings were planted into the sacks it took three weeks to grow. We even sell to our neighbors at a lower price. It is cheaper and accessible.”

Food insecurity among Kibera residents is increasing and urban agriculture is part of a larger solution needed to tackle hunger for the urban poor, say local community leaders. The local imperative seen in Kibera is now being mirrored by international organizations like the United Nations.

In 2014, “The 4th World Urban Forum, cited the need for policies and interventions to ensure that the increasing number of urban poor do not get left behind.” That forum placed strong emphasis on improving urban food security through urban agriculture.

High urbanization rates threaten the overall national food security improvement. To get a greater sense of the crisis, you need to look closer at the rates of food insecurity within urban centers because this data shows a much different picture than national statistics reveal. It can be difficult to find reliable data for some of these communities because the populations are in flux and there are just not enough government staff to produce reliable local numbers but some World Food Program reports show that urban poor globally are at higher risks of suffering food insecurity than those in rural regions.

Over 95 per cent of families in Kibera reported worrying about their supply of food in the last year. That information came from a 2013 study of urban agriculture in Kibera conducted by researchers associated with the University of Nairobi, Michigan State University, Northern Illinois University and Johns Hopkins University.

In 2009 a report from Oxfam found that more than half of Nairobi’s “food poor” were living in informal settlements like Kibera. People who are “food poor” can spend up to 80 per cent of their income on food as defined by that report.

Mamma Sammy has been a vendor in Toi Market since 2000. She says that food prices have shot up significantly since she started selling vegetables in the market. Prices have really changed because we were buying a crate of tomatoes $19 CAD, now we can buy as high as $90 CAD, she says.

“People are buying,” says Mamma Sammy. “But many are discouraged by the price so they aren’t coming as they were.”

Many urban poor have to subsist without good nutrition because there simply isn’t enough money to buy from the stores or markets.

“Urban populations in Africa are malnourished,” says Lee-Smith. “There is data that shows that, so when you have urban agriculture which is extremely patchy but widespread, people eat fresh food and are better nourished. The data shows that.”

Many are forced to eat cheap food with little vitamins and minerals. It’s not about health when you’re starving, it’s about feeling full.

“Ugali is the cheapest food in Kibera,” says Naimo. Ugali is a mixture of flour and water. Many use it as a side dish to soups and stews. “The poorest of the poor are finding themselves with only ugali — not accompanied by vegetables or meat. The prices of these products have increased in the last 10 years and are highest in the dry season.”

Click through the map to see how the percentage of undernourished people have decreased in many countries in the global south, including Kenya since the early 1990s.

Fast paced urbanization has put a strain on the rural-urban food driving the price of food up in urban centres; especially meat prices.

Shadrack Mbithi, 42 has been a butcher for ten years. The increasing prices have started to impact his small business that he runs in Kibera.

“I’ve lost customers because many will not afford to buy,” he says. “The price changes every year. For one to buy a small piece of meat it was $1.50 CAD, and now it’s almost $4 CAD.”

Many people in urban centres don’t have their own source of food. They shop at markets, like Toi or at the supermarkets. Inflation and lack of employment has exacerbated the food insecurity in Kibera because people just don’t have the money they used to provide for their families.

“The dollar you had for food last year, might be only a couple cents today,” says Bill Lijoh, co-ordinator of the agriculture sector support program for the Kenyan government.

Lijoh says women are disproportionately impacted by food insecurity in Kibera.

“If you are a mother with two children and if you have no food in the home, you will feel it more than the men,” says Lijoh. “[Women] are the ones who revert to food production.” Lijoh’s department is planning to invest more into urban farming activities for the city’s most vulnerable populations: women and youth.

The emphasis on women is a welcome decision for community leaders in Kibera.

“Woman can make a big role in changing food insecurity because she is the one most in touch to the children,” says Naimo. “The children cannot go to their father to say, ‘Daddy I’m hungry.’ They always go back to the woman.”

“Women can make sure she has her stock of food at home even when there is not food provided by the man,” says Naimo. “But the woman will always have the preparation of tomorrow in mind, more than a man.”

Local Kibera member of county assembly, Babu understands this imperative.

“In any city, in any country you go, agriculture has to be there,” says Babu. “Agriculture is more important than money.”

The 2013 Kenyan constitution also mandated that all citizens should have the right to food in section 43 (1) c. The city of Nairobi has enacted the statue of the Kenyan constitution which states that, “Everybody has the right: to be free from hunger and to have adequate food of acceptable quality.”

To integrate policies and programs to improve urban food security, Nairobi politicians are looking to an historic practice of urban agriculture, which has gone without official support for almost five decades.

Nairobi politicians have recognized that urban agriculture is, and always has been, part of the solution to tackle food insecurity within the urban setting and empower citizens through income generation.

Click the video to see how sack gardening increases food security and income generation.

Click “Urban agriculture reform” to learn how Nairobi’s new urban agriculture will promote urban agriculture in an attempt to curb urban food insecurity.