They’re young, in debt, and can be clueless about what that really means.

Rick Kim was forced to leave university when he could no longer afford tuition. (Photo: Ora Morison)

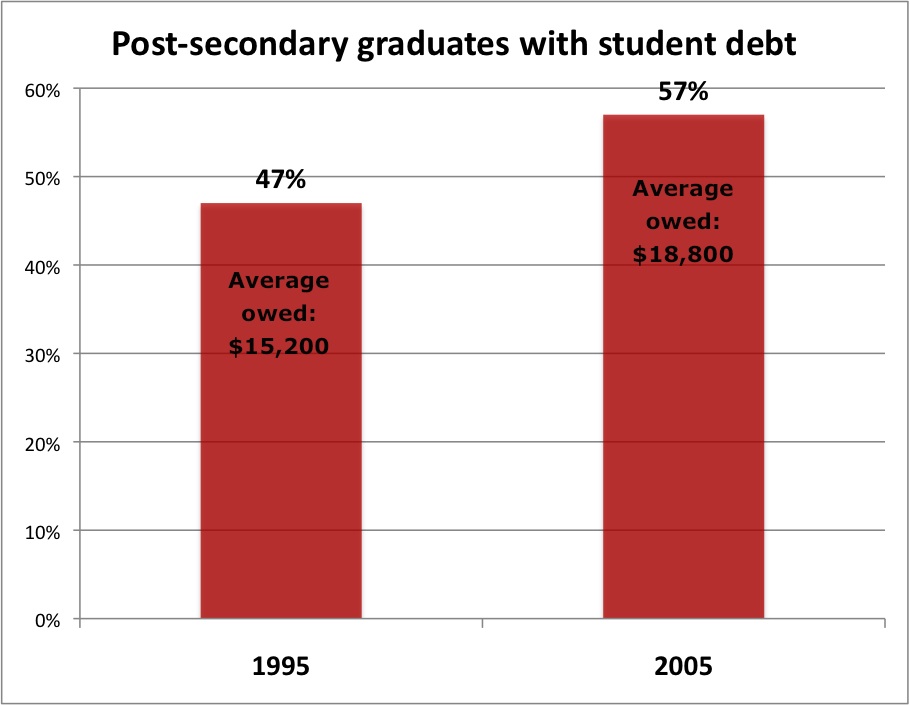

Young people today face higher levels of student debt and greater access to credit than ever before. They’re too old to have received lessons from new high school and elementary curriculum on financial literacy, and too young to be informed by life experience. Yet they are out in the real world now, making decisions that will affect their lives, financial and otherwise, for years to come.

Three quarters of undergraduate university students do not know their student loans will begin to accrue interest immediately after graduation, according to a Canadian Alliance of Student Associations survey from 2010. Despite this indication that many students have little understanding of their debt, college and university students are taking on student loans in record numbers.

“I didn’t really research how much school was going to cost me,” Rick Kim, a former University of Waterloo engineering student, says.

Part way through his four-year degree, Kim was forced to drop out of school when he couldn’t cover tuition and living expenses with his student loans.

“To begin with, I wasn’t a guy to save a lot of money,” Kim says.

A difficult semester where his marks dropped and he lost the chance to apply for co-op jobs, and Kim’s finances snowballed into a debt of $32,000 dollars. Kim was borrowing money from friends and using the food bank to make ends meet. He was forced to drop out of school when he couldn’t afford tuition. Click here to learn more about Rick Kim’s situation.

With their lives stretched out before them … and no plan

Would better money management skills have saved Kim’s academic career? An unexpected bump in the road, such as failed courses and loss of a co-op job, should be manageable if a person has a financial plan in place, credit counsellors say.

The problem for people in general, and young people especially, is they have a tendency to discount the future. Getting young people to simply pay attention to their money and plan for the future is the crux of any plan to teach this age group financial literacy.

Mélanie Nadon, a counsellor at Ottawa’s K3C Credit Counselling, says carrying a large balance or maxing out credit cards may not have bothered some of her clients when they were younger, but five or 10 years later when they want to buy a house, they are cursing their poor credit score.

“I didn’t really research how much school was going to cost me.” – Rick Kim

Many young people don’t realize the impact their financial decisions today can have on them years down the road, Nadon says. Click here to see how one credit counsellor shows Rick Kim how to get his finances in order.

Credit cards are increasingly becoming a danger for young people with little or no income. With 72 per cent of Canadians aged 18-29 owning a credit card, the proportion is roughly equal to the number of young people with a savings account (74 per cent), according to a survey commissioned by the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada.

“The banks are almost throwing [credit] at them,” Ellen Roseman, a personal finance columnist with the Toronto Star, says. “They want you to take it even if you have a fair bit of debt already.”

“Young people growing up with this widespread availability of credit may not be aware of how hard it is to dig yourself out of a hole,” Roseman says.

Cards marketed specifically as student credit cards can come with features such the ability to withdraw $2500 in cash advances per day, at a 19.4% interest rate. Some also appear to specifically entice young people with customizable designs.

These cards often don’t require the student to have any income. They are marketed as a tool to build a credit history, but a first foray in to the world of credit has the potential to hurt rather than help your credit score, and finding help when you’re young and in debt isn’t always easy.

Not finding help in all the right places

Kaitlin MacVicar was put off investing when she didn’t know what to make of one bank’s investment manager’s sales pitch. (Photo: Ora Morison)

Kaitlin MacVicar is 25, working at her permanent first job and chipping away at her $35,000 worth of student loans. Before this, she held a series of several-month-long contract positions that made making regular payments toward her student debt extra stressful. Despite this, MacVicar was determined to keep up to date with her student loan repayments.

Weeks ahead of her first payment, MacVicar tried to contact the Ontario Student Assistance Program (OSAP) about how to make regular payments. She found herself navigating seemingly endless menus on her touch-tone phone and unable to speak to a real person. Frustrated, MacVicar had to wait until OSAP called her, looking for her first payment, in order to speak to someone. Now late on her first payment, it wasn’t the way MacVicar had planned to start her repayment process. She says she has found the OSAP system opaque and hard to navigate.

Click here to learn more about Kaitlin MacVicar and the other money management problems she has encountered.

Who can you trust?

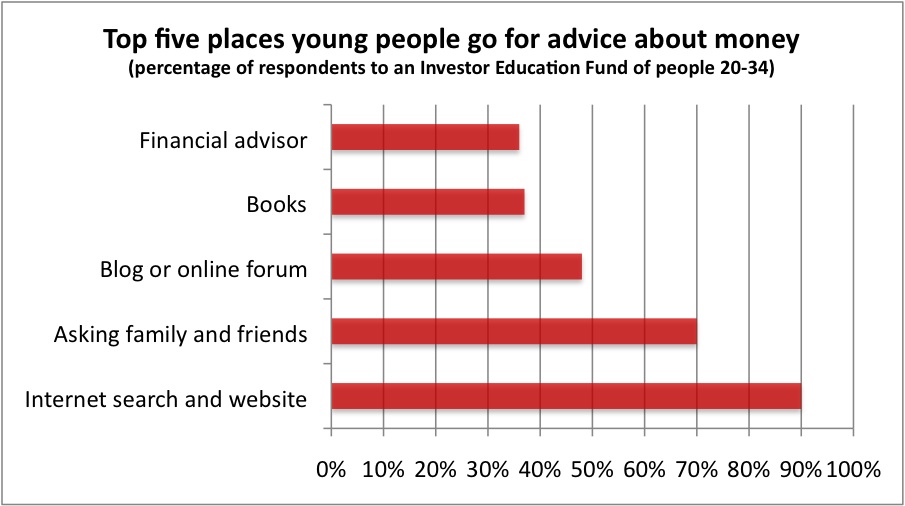

It’s often difficult for young people to get personalized financial advice from someone who will take the time to sit down with them and explain their options in detail. Without much in the way of assets, young people tend to be an unattractive market for financial advisers.

“It’s more profitable to deal with people who can afford the product and have a lot of money to invest,” Heath Haughton, an Ottawa-area financial adviser, says.

Haughton estimates about 15 per cent of his clients are under 30, and these are mostly children of his older clients.

“There are a couple of sound business reasons why it doesn’t make sense for an advisor [to deal with young people,]” he says.

Even though he says young clients represent potential for good business in the future, Haughton says he would rather seek out people who will help him earn profits now.

While Haughton agrees learning about managing your money, saving and investments is an important skill, he says it’s not his job to teach these things in the private sector.

“Banks are profit-making organizations. We can’t forget that” – Norah Foster

Norah Foster, another credit counsellor at K3 Credit Counselling, agrees the private sector is not the place to teach these lessons. Foster has helped many young people work through their financial problems and set up a budget. She says banks can also give valuable advice to young people, but as private companies, they can’t always be relied upon for unbiased advice.

“They do provide financial literacy, but the underlying thing is the banks are profit-making organizations. We can’t forget that,” Foster says.

Other places young people can turn for advice are government-sponsored websites, not-for-profit counselling agencies and communities of blogging amateur finance geeks. Are young people using these sources to get the information they need to be financially healthy? For people like Rick Kim, easy access to credit and loans didn’t come paired with the need or desire to learn about how to manage them.

Boosting financial understanding for young people is important because they are in a uniquely vulnerable situation: little to no income, relatively large student loans, easy access to personal credit, and a tendency to believe financial decisions can be put off until they get older.

Getting young people to care, and care today, is the first step to solving the problem