Chatbots, at your service

Businesses are turning to chatbots to interact with customers and deliver services. In the immigration and refugee field, the technology has merit – if it has the right support.Several months after 25-year-old Muhammed Idris moved from Boston to Montreal to study data science, he learned that a number of his relatives would be moving there, too. His family members – three cousins and an aunt – were Eritrean refugee claimants who had been temporarily living in Saudi Arabia. It was 2015, and Idris began volunteering at a local YMCA shelter to support the overburdened office. It was his first foray into the claimant and resettlement process and he saw firsthand how claimants arriving in Montreal navigated the transition into their new home.

Idris also witnessed this experience through another connection: Ahmed Saeed, one of his closest friends. Like Idris’ relatives, Saeed was originally an asylum seeker from Eritrea who had travelled to Montreal via Saudi Arabia. And as it turned out, he had developed a reputation within his community for giving resettlement advice to other displaced people in Montreal. Inspired by Saeed’s efforts, Idris wondered if there was an app that might be able to provide the same service for more people while supporting service providers feeling the strain.

This curiosity compelled Idris, now 28, to build a chatbot along with Saeed and a small network of friends. Its name was Atar, and it would serve as a blueprint for the first chatbot aimed at refugee claimants in Canada.

A chatbot is an AI-based computer program that mimics human conversation, typically with the goal of providing information or helping to complete a task. They’re a tool used by companies and organizations to help their users achieve anything from ordering a pizza to diagnosing a medical condition. According to Juniper Research, a UK-based market research firm, chatbots are projected to save businesses in the retail, banking and healthcare sectors more than $11 billion a year by 2023. But besides sales and customer service, chatbots are also increasingly used for humanitarian purposes.

The appeal is similar: bots can provide instant support at any time of day, they are offered in more languages and creators can track common requests to identify areas of highest need. The UN’s World Food Programme recently launched an app to detect and treat malnutrition in children, which includes an offline bot to provide followup care (an online version is planned for use on Facebook Messenger). Another example is Microsoft and the Norwegian Refugee Council’s chatbot called Hakeem, which will help educate refugee youth living in circumstances where access to school is limited. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada has also jumped on board. According to federal documents, the department paid just over $150,000 for “a chatbot with AI capacities” in August 2018. The bot is currently delivered through Facebook Messenger, interacts directly with clients and has the ability to defer more complicated requests to an agent. The federal government has previously stated that it plans to introduce chatbots and predictive modelling to more of its departments.

Meeting Atar

When Idris and his friend first created Atar, they needed a platform to build it on first. Beginning in 2016, it eventually took the form of a “set of developer tools” known as Compass, which combines digital communications and AI to build products.

“You can think of Atar as being one of those products,” Idris explained.

Atar is a FAQ chatbot, which means it’s programmed to answer common questions. It also doesn’t allow users to type their own questions, but rather guides refugee claimants through the tasks they want to accomplish. The app is designed to address the tasks a claimant would need to complete within their first few weeks of arrival, like finding a place to stay, scheduling a medical exam or getting referred to relevant agencies.

In the fall of 2017, the Compass team tested the app by recruiting 300 refugee claimants in Montreal and Toronto, as well as asylum seekers interested in coming to Canada from overseas. Participants were found through social media and digital messaging apps and primarily came from Eritrea, though claimants from Yemen, Chad and Somalia were also included.

After conducting post-testing interviews with claimants, as well as consulting service providers, the team deemed the bot a success. Feedback from providers indicated that 20 per cent of claimants had abandoned seeking help because of wait times to access services – a problem a bot with instant answers could sidestep. Responses from refugee claimants themselves suggested that a quarter of claimants had been sent to the wrong provider in the past or were misinformed about eligibility requirements, which were details Atar had verified.

One issue the team encountered, however, was a privacy tradeoff.

Eventually, Atar caught the attention of the UNHCR. While the agency became an official partner for the tool, it was unable to provide the financial assistance Compass needed.

It would be the lack of funding for the project – from the federal government, other organizations or elsewhere – that would alter the rest of Atar’s development. Despite the backing of the UNHCR and its success as a proof of concept, the bot languished in subsequent phases.

“If you don’t have the funding, you better damn well be interested in the cause and see a potential in it…You’re not going to charge refugees.”

– Muhammed Idris

“If you don’t have the funding, you better damn well be interested in the cause and see a potential in it,” Idris said. “Impact investors are not going to give you anything until you can figure out a business model. That’s difficult in and of itself within the sector. You’re not going to charge refugees.”

Idris said that over the past three years, the project has received about $3,000 in outside funding from Concordia University’s Refugee Centre. He funds whatever else he can out of his own pocket, but estimates the project needs at least $300,000 to implement a longer-term strategy, partner with other organizations and hire more people. When IRCC put out an expression of interest in 2017 offering funding for new projects to improve settlement service delivery, Idris submitted a letter of interest. But he wasn’t chosen for the next round, he thinks, because bigger organizations or ones more well-known to the government got a slice of the pie instead.

A funding boost would also help Idris and the Compass team with the biggest setback they currently face: figuring out how to continuously update Atar’s data in an immigration and refugee sector that is constantly evolving.

Challenges in a broad sector

Idris says updating information is particularly important to address in the immigration and refugee sphere because the “cost of misinformation is high”. Unlike a customer service chatbot for a pizza joint that might mix up a topping, directing a refugee claimant to the wrong resources or giving them the wrong deadline for a form could have serious consequences. Making sure information is consistently correct also avoids scenarios where a bot provides false information, unbeknownst to its creators.

Atar’s ability to receive and share new information works, but Idris said it would take untold hours to update it for every policy or organization change across multiple levels of government.

It’s an issue other chatbot developers in the sector have avoided by reining in their focus to something more specific.

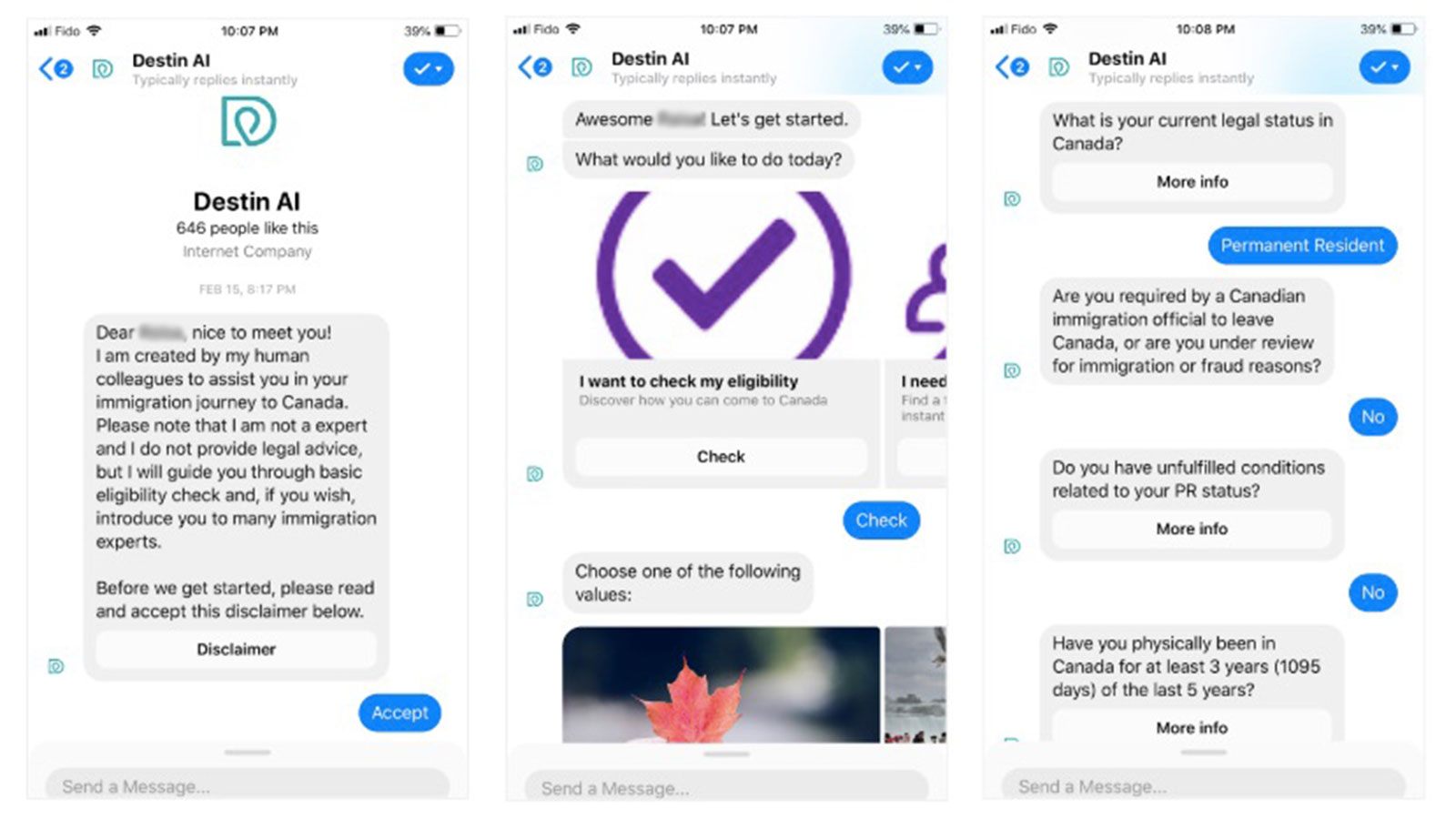

Nargiz Mammadova, who created an immigration-based chatbot called Destin in 2017, zeroed in on providing eligibility checks for potential immigrants and international students. Users can select their stream in a Facebook Messenger window and answer a series of questions from the bot to determine their eligibility. If successful, they are invited to book a consultation with an immigration lawyer or consultant. While users have to pay for consultations, Mammadova says the checks themselves cut down on time spent with costly experts.

“I created Destin out of necessity,” said Mammadova, who emigrated to Canada from Azerbaijan. “I realized that immigration is like a black box. People who are even educated and have good experience with English have a hard time to navigate the process.”

A sample of Destin interactions that a potential immigrant might have while navigating the app. [Photo © Raisa Patel]

Destin doesn’t answer questions about Canada’s three refugee streams, but Mammadova said applying for refugee status in Canada is so confusing, sometimes refugees have asked her for help anyway. She tries to refer them to helpful organizations when she can.

To address the issue of updating, the bot is coded to automatically update itself with information pulled from the federal government’s immigration website.

“It’s a process you need to be cautious about,” Mammadova said. “You need to be aware of those changes.”

One example of this is keeping track of the scores used in Canada’s express entry immigration stream. Applicants eligible for express entry complete an assessment of their skills, education and language ability (among other factors), which generates a score. This number is then ranked within a pool of potential candidates. The minimum accepted score constantly changes depending on demand, so Destin must be aware of the new threshold every time it changes.

“The government releases this data and past data, and the system is smart enough to pull this information out and update it itself,” Mammadova explained.

While Atar is capable of doing the same, Idris realized that his vision for the bot was outside his scope as tech expert. What he really needed was input from subject matter experts, or the agencies, organizations and departments holding all the new information he required. So in early 2019, the Compass team decided to pivot.

“The Holy Grail would be to ask anything on it, like a Google search. But that’s far from reality.”

– Muhammed Idris

Bringing bots to service providers

“The Holy Grail would be to ask anything on it, like a Google search,” Idris said. “But that’s far from reality.”

Idris said he found it difficult to convince service providers to partner with Atar because they were more interested in developing their own apps. He’s now figuring out how to bring the technology to organizations themselves, a task that would involve mapping out every provider’s services and translating them into a bot they can use on their own. Idris is even happy to open source his code if it means finding a more sustainable solution.

While a singular bot might have been Idris’ original goal, he is right that individual organizations could benefit from delivering accessible and low-cost services. Legal chatbots are an emerging use of this technology, and could fill a gap in places like Ontario, which entirely eliminated funding for refugee and immigrant legal aid earlier this year.

But there might be some hope for Atar yet. A TED Talk with Idris and his bot recently hit the internet, and suddenly the phones are ringing.

“There’s been an outpouring of interest and support,” he said, adding that organizations from the U.S., Australia and across Europe have expressed a desire to collaborate. Whether or not that translates to concrete funding remains to be seen, but Idris is not closing the lid on Atar just yet.

Idris fiddles with Atar’s code. He’s listening to Immigrants (We Get the Job Done), a track from 2016’s The Hamilton Mixtape. It’s a song the data scientist referred to often while developing the app. [Photo © Raisa Patel]