Governing ethical AI

The use of artificial intelligence and digital identity might streamline the refugee experience, but what if these technologies harm more than they help?Immigration lawyer Petra Molnar insists she’s not a fearmonger.

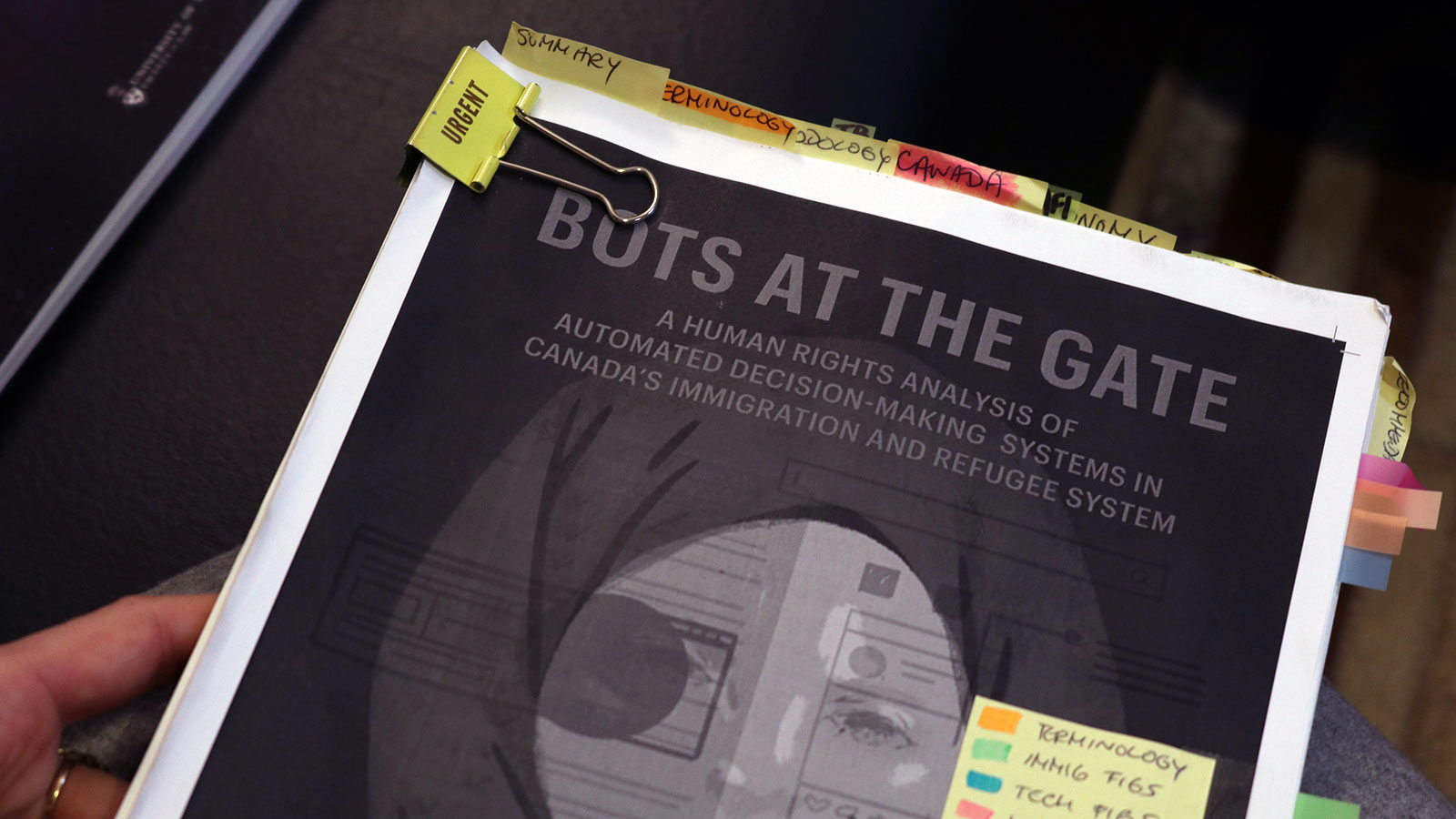

In September 2018, Molnar and human rights researcher Lex Gill issued a damning 88-page report warning about the use of artificial intelligence in Canada’s immigration and refugee system. The report was published through the University of Toronto’s human rights program and the Citizen Lab and bore a chilling title: Bots at the Gate.

“The ramifications of using automated decision-making in the immigration and refugee space are far reaching,” the report noted.

“The nuanced and complex nature of many refugee and immigration claims may be lost on these technologies, leading to serious breaches of internationally and domestically protected human rights, in the form of bias, discrimination, privacy breaches, due process and procedural fairness issues, among others.”

Petra Molnar in February 2019, visiting Ottawa for a symposium on ethics and AI. Molnar said the idea behind Bots at the Gate was sparked a year earlier, when she first read about new technologies being used in the immigration and refugee sector. [Photo © Raisa Patel]

But Molnar maintains that she’s not trying to instill terror over the use of AI in these systems. Her goal is to create nationwide dialogue about the responsible use of automation in government, a trend that is no longer speculative.

“It’s important to have a balanced discussion,” Molnar said, “because fear mongering isn’t really going to get us anywhere.”

Bots on the ground

Artificial intelligence in this context refers to a form of technology that sorts through data to mimic the human decision-making process. In Canada, using these tools for automated decision-making isn’t something the federal government is thinking of using: it’s already doing so.

For the past several years, Ottawa has been quietly developing AI solutions to streamline a number of its administrative processes in the immigration and refugee sector. As early as 2014, the government has used predictive analytics to sort through immigrant and visitor applications. Then, in an early 2018 request for information about AI tools for several federal departments, it was revealed Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) was seeking an “artificial intelligence solution” for a number of processes.

In the request, IRCC – in partnership with the Justice Department – sought a “broad-based solution that can analyze large volumes of immigration litigation data to assist in the development of policy positions, program decisions and program guidance.” The notice mentioned using historical data, identifying factors to predict successful litigation outcomes and putting this information in the hands of administrative decision-makers.

“In other words,” Molnar’s report explained, “the proposed technology would be involved in screening cases for strategic legal purposes, as well as potentially for assisting administrative decision-makers in reaching conclusions in the longer-term.”

Last year, IRCC also revealed it has been using an AI tool since early 2018 to triage a large volume of temporary resident visa applications pouring in from India and China, a project slated to cost the department more than $850,000.

Garbage in, garbage out

In federal departments, automated technology can provide significant time and cost-saving benefits. IRCC is often beleaguered by application backlog and sometimes boasts processing times that span multiple years. As Molnar notes, however, the significance of immigration and refugee decisions means applications must be handled carefully.

But instead of providing a solution, artificial intelligence can introduce a serious problem: bias.

In an algorithmic context, bias refers to a simple premise many experts classify as “garbage in, garbage out”. Essentially, if the quality of data entering an algorithm is poor, it will generate poor results. In 2015, Amazon discovered an AI system it was using to select possible job candidates was unintentionally sexist. That’s because it was trained on 10 years of resumes from successful applicants – who mostly turned out to be men. In another example, researchers from MIT and Stanford University found that facial recognition software was much more successful at identifying white men than it was black women. A data sample that predominantly consisted of white faces was the culprit.

“I struggle with this presupposition that technology is somehow less biased than humans, because it’s created by human beings.”

– Petra Molnar

But humans are biased too, which includes administrative decision-makers who make life-altering calls about who gains entry into Canada. Documented cases of bias or potentially culturally insensitive language can be found in notes from immigration officers, which means this is the sort of data automated systems will rely on to sift through immigration and refugee applications.

“I struggle with this presupposition that technology is somehow less biased than humans, because it’s created by human beings,” Molnar said of the belief that AI might be more fair than human decision-makers.

It would be reasonable to assume that Canada has a strict set of regulations to govern the use of such technology, particularly when an automated system’s thought process is not as transparent as a human one. The reality, however, is not so clear.

Who’s in charge?

In March 2019, then-Treasury Board president Jane Philpott announced the publication of Canada’s Directive on Automated Decision-Making, an extensive policy document outlining how government should properly develop and deploy decision-making AI. The release of the directive marked the country’s first step toward monitoring the use of AI in federal departments. But it was published mere hours before Philpott’s resignation from cabinet, so the directive quickly disappeared from public consciousness.

While it may be a relatively unknown piece of policy, it’s a critical one. The directive is a sweeping guide intended to reduce the risk of automated systems. It outlines rules for establishing transparency, like making sure it is clear how systems work and providing explanations for AI-based decisions; testing for unintended biases algorithms may generate on their own; ensuring humans can intervene in a system’s decision-making process when necessary and listing consequences for a failure to comply.

The directive also requires the use of an Algorithmic Impact Assessment (AIA). Currently in draft form, the AIA is a 57-part questionnaire that assesses the details of a proposed system, like what parts of the system will be controlled by AI, or where the data behind it came from. The system is then assigned one of four impact levels, which correspond to how much the system will impact someone’s life and how reversible the decision it generates is. The level then determines the additional review, testing and transparency requirements needed for the system.

“It is, in my opinion, a step in the right direction,” said Mirka Snyder Caron, an associate at the Montreal AI Ethics Institute. “It gives a checklist approach, it provides different AI impact assessments varying on the impact on the rights of individuals.”

Molnar believes it’s a good step too, and has had positive discussions with Treasury Board about the guidelines.

“At the same time, it’s a directive, not legislation,” Molnar cautioned regarding the enforcement of the policy. “There’s only so far that it can go.”

Molnar was unable to say whether legislation is needed at this point, but other countries have started entering that space. In early April, the U.S. took the plunge by introducing a bill to regulate the use of automated decision-making systems. Named the Algorithmic Accountability Act, the bill involves testing a company’s systems for bias, conducting impact assessments (much like the Canada’s AIA tool) and addressing any red flags arising from these assessments within a specific time period. Across the pond, British parliament established a Committee on Artificial Intelligence back in 2017 to better understand the economic, social and ethical implications of the technology.

Snyder Caron recently joined the Montreal AI Ethics Institute, a civic engagement group that helps people build AI tools ethically. [Photo © Raisa Patel]

Aside from Treasury Board, two other bodies handle AI development in Canada: the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) and the Chief Information Officer Strategy Council (CIO). Neither governs AI, but CIFAR’s $125 million Pan-Canadian Artificial Intelligence Strategy researches the ethical and legal implications of the systems and is training the next generation of AI researchers at its three federally-funded institutes.

“One of the things that we are dedicated to and focusing on is making sure that as many students as possible get training around the ethical development and application of AI,” said Elissa Strome, the strategy’s executive director. “It’s really important to us that not only do they get the technical skills but they also get some understanding of these ethical questions and the other social implications of AI.”

The CIO Strategy Council, on the other hand, is currently developing a set of standards to shape the private sector’s ethical development of automated decision-making systems.

“They’re voluntary standards, but really for a product to be deemed to be following ethical frameworks and ensuring privacy, [the private sector] is going have to be able to demonstrate that they have followed those standards,” Strome explained.

What next?

As for Canada’s fledgling attempts at regulation, there are still points of weakness.

“There are concerns that [the directive] won’t be sufficient for the immigration process. It is a very broad directive and it’s meant to be applied across various administrative organizations,” said Snyder Caron, referring to potential human rights abuses in the immigration and refugee system.

“There are issues which I believe should be tackled specifically for immigration and it would be very nice to see, at least on the first step, specific islands in the context of immigration.”

The “specific islands” Snyder Caron is referring to could become a reality where one area of the directive is concerned: its impact assessments. The draft questionnaire is not highly tailored to different uses of automated system, but Treasury Board hopes to change that.

Ashley Casovan, who works within Treasury Board’s Secretariat, said there are possible plans to create “extensions” for AIAs. That would mean making specific assessments for tools in different sectors, like immigration or health.

In terms of bias, Casovan cited the directive’s requirement to further review projects that have a more significant impact on human rights.

“We want whoever is doing the peer review to do not an analysis of the data, but the data and the potential algorithm, the methodology, in tandem with one another, to ensure that bias would be caught,” Casovan explained.

References to automated decision-making have also appeared elsewhere in federal doctrine: Canada’s Immigration and Refugee Protection Act approves the use of the technology. That’s according to a 2015 amendment buried in the legislation, which was added to permit the use of electronic systems to administer the Act.

“Let’s say my client comes to see me and says, ‘What are we going to do about this? How can we challenge it? Under what grounds can we challenge it?’ Then it becomes problematic because do you challenge it under the existing Act?,” Molnar said.

“For greater certainty, an electronic system, including an automated system, may be used by the Minister to make a decision or determination under this Act, or by an officer to make a decision or determination or to proceed with an examination under this Act, if the system is made available to the officer by the Minister.”

– Section 186e.1, Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

“That’s when it gets tricky. What do you bring to court? And how do you make judges understand these intricacies around decision-making when you’re now dealing with a whole other system of cognition? It gets very complicated, very fast.”

Molnar has identified a critical consideration regarding Canada’s push for AI: the fact that resolving automated decision-making disputes will fall to Canada’s legal system. But where the aftermath of AI is concerned, it’s a system that might not be ready.

Molnar holds a personal copy of Bots at the Gate, covered in notes. It’s been seven months since the report’s publication, and the immigration lawyer is still surprised by the ripple effect it created. [Photo © Raisa Patel]