Bring back our girls

Fifty-seven of the girls managed to escape by holding on to tree branches and jumping off the lorries. But the rest were driven deep into the Sambisa forest, which was Boko Haram’s hideout for much of its eight-year insurgency.

The Nigerian government was slow to respond. Then President Goodluck Jonathan didn’t speak publicly about the incident for two weeks. Activists and other citizens worked together to spread the word about this abduction. They criticized the government, and demanded that it take action. The outrage in Nigeria captured the world’s attention and one of the biggest social media campaigns was born – Bring Back Our Girls.

The #BringBackOurGirls hashtag was on all corners of social media, in the U.S. White House, on red carpets of the 67th Cannes Film Festival, and in rallies held in cities around the world.

In the days after the abduction, international governments offered to help Nigeria find the girls. The world was crying in unison.

“Abductions had taken place before then,” said Aisha Yesufu, the leader of the Bring Back Our Girls group in Abuja. “Women had been abducted, children had been abducted but this was the first time that in a school setting, this large number of children, girls, were carted away by the terrorists.”

On Apr. 30, 2014, disgruntled Nigerians took to the streets across the country to march and protest the abduction and government’s inaction. The group in Abuja marched to Nigeria’s National Assembly.

The daily sit-out

“What are we demanding?,” a young woman cries into a microphone.

“Bring back our girls now and alive,” the dozen other people in attendance respond in harmony. They are all seated in a semicircle, facing the busy highway yet almost unaware of the cars that zoom past. It is 5 p.m. in Nigeria’s capital, Abuja. The gathering is on the grounds of the Unity Fountain, one of Abuja’s most famous landmarks.

“What are we asking for?” the young woman probes again.

“The truth, nothing but the truth,” her audience chants.

“And when shall we stop?”

“Not until our girls are back and alive.”

“When shall we stop?” she asks again.

“Not without our daughters.

This has been this group’s signature cry for almost three years. They have met every evening, in every weather condition and on every day of the week, since April 2014 to protest the Chibok abduction.

Just after the group was formed, as many as 200 people attended the daily meetings to stand in solidarity. Even more took to social media. But as time went by, the number of people crying in unison dwindled. On this evening, there are only 16 people.

“It is sad that the world has moved on but there are people who have not moved on,” Yesufu tells me. “Their parents have not moved on.”

Recommendations and demands

Eighty-two of the young women were released in May, after negotiations between the Nigerian government and Boko Haram, brokered by the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Swiss government.

In October 2016, 21 of the former school girls were freed after a similar process. Three others found ways to escape captivity on their own.

The 24 escapees from 2016 are being kept in government custody. Nobody knows for sure what’s happening to them. The only thing that’s clear is that they cannot go home to their families. According to at least one source, the military says it is unable to keep them safe if they return home.

“To a lot of the families, it feels that our daughters were first abducted by Boko Haram and now they are being kept by the government,” said Chitra Nagarajan, a humanitarian expert who works on peace, security and human rights in northeastern Nigeria.

The Bring Back Our Girls group has pressed the government for policy changes. It wants the adoption of an official national register, a database that can track the number of people who go missing or who are in captivity.

It also wants the government to establish and fund a standard rehabilitation process for all of the girls who are rescued or who manage to escape Boko Haram’s clutches on their own. It has suggested what this process should look like. The government hasn’t said whether it will implement the recommendations of the group.

Criticisms of the campaign

“I don’t think it (the Bring Back Our Girls campaign) brought attention to the abductions. I think it brought attention to what happened in Chibok,” said Nagarajan.

This has been one of the biggest criticisms of the campaign.

“To this day whenever anybody reports on the release of women and girls, they have to say whether or not they are the Chibok girls,” she said. “I feel like what it has done is it has created a hierarchy of humanity. If you’re not from Chibok and if you weren’t those girls who were taken, it doesn’t really matter what happens to you,”

In fact, unlike those whose abductions didn’t capture the imagination of the world, the first group of Chibok girls who escaped have had special opportunities. Some of them have received scholarships to go to schools in Nigeria and the United States.

The attention, although well-intentioned, has not always been good for the Chibok girls.

Boko Haram treats them as prized possessions and is very careful not to let them escape, said Nagarajan. And those who have been released cannot live their normal lives.

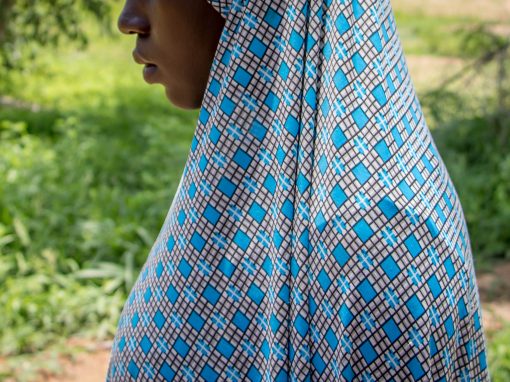

The Chibok girls have now become young women. But the world continues to remember them as girls. They were girls when Boko Haram took them. More than 100 of them still remain in captivity after three years.

“As long as there is one person who is out there crying and demanding for the return and rescue of our Chibok girls and other abductees, the whole universe will take that up and it will keep echoing,” said Yesufu.

Yesufu maintains that she won’t stop talking about the Chibok girls until every one of them returns from captivity.

Click on an image below to read the story