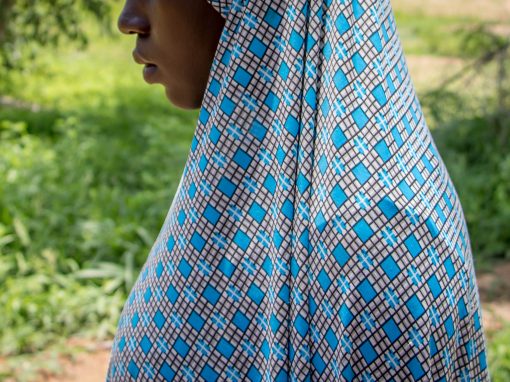

Fatima

Photo gallery

When she finds work, she is not paid more than 500 naira, about $2 CAD, for the day’s sweat. This is money that supports her and her seven children.

But Fatima’s life was once different.

Gwoza, in northeastern Nigeria, is the town of Fatima’s birth. She lived there with her husband and children until 2014. Her husband was a butcher. They owned more than a dozen goats and chickens. Fatima made an income from grinding maize, rice, and millet in a community where many did not own personal blenders to grind their food.

One Tuesday, Fatima was in her kitchen cooking from the bag of rice her husband had bought the previous week for Eid, a Muslim festival. She was alone except when two of her youngest children came around to play. Her husband and other children were in another part of the house.

She was still cooking when she heard the gunshots.

When I asked Fatima how she felt once she knew Boko Haram was in her village, she laughed, surprised at my question.

“We put death in our minds,” she told me in Hausa.

By their second day in Fatima’s village, the Boko Haram men started searching houses. Fatima said they were armed with guns.

At the time, the terrorists forcefully conscripted men and they killed those who refused to join them.

The Gwoza men started to flee to safety. Fatima’s husband left for a nearby town.

Boko Haram arrived at her doorstep two days later, looking for him.

“Where is your husband,” they asked.

“He is not around,” she responded.

“Where are you hiding him?”

“I am not hiding him. He travelled and is not around.”

“Is anyone under the bed?”

Her older sons were hiding there. They were 13 and 15 years old.

Fatima was scared.

She left her sons there, and returned home to her younger children and another nightmare. Boko Haram was still terrorizing her community. They weren’t holding people captive. They didn’t have to.

“They said to people who left, ‘go, we will come and find you wherever you go,’” said Fatima.

A week later, she had endured enough. She decided to take her chances and flee in the night with her remaining children.

The reunited family lived at a primary school that housed people who had escaped Boko Haram violence.

There was no money. There was no work.

And then a rumour started making the rounds. Boko Haram was planning to hit Madagali. But with nowhere else to go, her family stayed and hoped.

The terrorists came into Madagali on a killing spree less than three weeks later.

Fatima recalls running with her family to hide in a house packed with strangers who were also fleeing. Boko Haram conducted random house searches, hunting down the men, in particular.

“They (Boko Haram) said they would not kill people indiscriminately,” said Fatima. “They only wanted to kill those who were part of vigilante groups.”

The vigilante groups were made up of local hunters who worked with the Nigerian army to fight Boko Haram. With knowledge of the local terrain, they infiltrated communities with the terrorists and gave intelligence to the military. Boko Haram hated them.

When the killings stopped, the family went to stay with a relative who lived in Madagali.

“When the children had fever, sometimes, there was no place to buy medicine,” said Fatima.

A capsule of Paracetemol, the equivalent of a Tylenol, was more than they could afford.

There were days when her children ate only because the people around her were generous with their food.

“We just trusted God,” she said.

And then one morning, things got even worse. The terrorists decided to leave Madagali to set up camp in the bush and they forced the entire village to go with them.

“Those who didn’t want to leave were shot and abandoned,” said Fatima.

They were on the move for two months. Boko Haram finally decided to settle the villagers in a spot deep in the bush.

Their lives were not their own.

Fatima was pregnant by the time they arrived, and her baby girl was born in captivity. A few months in, the terrorists murdered her husband. He was killed in front of their children. When she told me about this, her tone was flat and her face showed no obvious emotion, as if she were speaking about an ordinary event.

She spoke instead about surviving on some of the food her husband had bought before he was killed and how her close community helped her out.

Two months after her husband’s death, government soldiers successfully raided the camp, routing the Boko Haram terrorists in a gun battle.

When the soldiers broke into Fatima’s house, she was lying on the floor, hunched over her children to protect them from stray bullets.

In Fatima’s house, a small bag of rice rests on one of the tree-branch pillars. Sitting under the bed is a plastic bowl filled with coal. A plastic jerry-can tucked in one corner is the storage space for raw beans. These are some of the donations she has received from non-governmental organizations that visit her community. Her father also supports her and her children with the little he has.

But this is not enough.

She suffers chronic chest pain, backaches and a stomach ulcer that almost prevented her from completing the last Ramadan fast.

Her youngest child is almost two years old.

Click on an image below to read the story