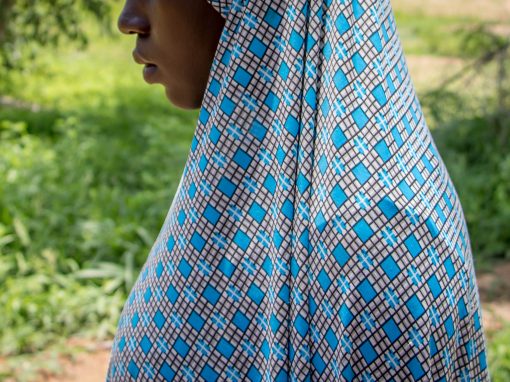

Maryam

By the end of the day, she would have almost 500 naira, about $2 CAD, clenched in her fist. She had to sell 50 wraps to make that much money. And on most days she succeeded, sometimes even as early as mid-afternoon.

One sunny day, she had just set up when she heard loud sounds.

Prrah! Prrah! Prrah!

Gunshots.

She had heard these before, when soldiers came to her village. And then she heard something else.

“Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar!”

Familiar words. She said them when she lifted her hands in prayer. But the men who shouted these words did not have the calm of prayer in their voices.

From where she sat, she could see as her village secretariat, not far away, was swallowed up in flames. She did not wait to watch it burn to the ground. She ran into her house.

“Everybody was scared,” she said to me in the Hausa language.

That was the day she heard about Boko Haram.

That morning’s incident added her village in Madagali, in northeastern Nigeria, to the list of places where Boko Haram has unleashed terror.

Later that evening, Maryam told her mother she wanted to go to Mubi, a northeastern town she considered safe. It was 100 kilometres away. Her uncle lived there.

Maryam’s mother gave her some travel money and she set out to Mubi the next day, with her younger sister.

Mubi was as safe as she imagined, but she missed home. She heard that her village had been peaceful since she left. So two weeks later, Maryam and her sister packed their bags again and returned home.

But Boko Haram was still close by.

“When they took Gwoza, we were not scared,” Maryam said about Boko Haram’s bloody raid in a town just 24 kilometres away from hers.

She remained in Madagali with her family, optimistic that the terrorists would not strike. But Boko Haram returned, and came knocking on her family’s door.

She uses Ramadan, the Islamic month of fasting, as an event marker. By her estimate, these events might have happened two Ramadans before I spoke with her in summer 2016.

Maryam was moved around. She was taken to a Boko Haram base in Gulak, which was about 20 kilometres from her hometown. Boko Haram fighters left there regularly to raid nearby villages and towns, destroying property and killing. They always returned in larger numbers than they left – with even more women.

Before long, she was relocated again to the Sambisa forest, which served as Boko Haram’s hideout for much of its eight-year insurgency.

In Sambisa, she met some of the 219 young women from Chibok whose abduction from their school in 2014, captured the world’s attention. She still remembers their names.

Halima.

Falmata.

Maryam.

But whatever friendship she created with them was short-lived. The young women from Chibok were whisked away to another location.

Maryam’s Boko Haram marriage made her homesick. Her husband hit her once, and disrespected her all the time.

“I did not like my husband,” she said. “There was a lot of stress and there was embarrassment and my parents were not there.”

“I wanted to see my parents.”

Her chance at freedom came when a faction of the camp decided it would move to another part of the Sambisa forest. Her so-called husband was part of that group. But she refused to leave with him. She wanted to return to her parents. Maryam said he didn’t force her. He left without her.

Being on her own came with different struggles. She ended up in a makeshift shelter in the forest for unmarried women. Raindrops trickled from the roof into her room when there was a heavy downpour. She had to find her own food and water. On many days, she got these only if she begged.

Every struggle made her even more homesick.

She had a distant male relative in the Sambisa forest, too. She told him about how badly she missed her parents. He helped her plan an escape.

When Maryam fled Boko Haram, three other women came with her. They were caught two days later.

They spent days wandering through the forest before they finally found a farm. They were in Limankara, less than 20 kilometres away from Maryam’s hometown.

“Blessings that you are out of their (Boko Haram’s) hands,” the women they met at the farm said to them, on learning about their escape.

Maryam walked for days, wandering the forest before she arrived at a farm in Limankara, a town in northeastern Nigeria.

Members of the group searched Maryam and the other women before handing them over to the soldiers, who gave them food and water.

After that, she told me, came the questions. About where they were coming from. How they escaped. The Boko Haram members they knew. The young women from Chibok. Why Maryam and the other women did not escape with them. And where the young women could be found.

It was evening by the time they finished answering all these questions. They were given a space to sleep. Maryam said the soldiers told her they would take her to her parents in Madagali, the next day.

But it didn’t happen. They kept her at their base for a week before transferring her to a government-run camp for displaced people in Mubi.

The camp in Mubi

The camp entrance has a prominent sign that rests on brick pillars. The words, “Welcome to Mubi Burnt Brick Industries Ltd” are displayed on it. Some Nigerian soldiers are stationed at this entrance. They decide who gets to enter and who is turned back.

On the day I visit, there are signs of help from around the world. The logos of non-governmental organizations are appended to tents and other relief materials. Oxfam. The International Committee of the Red Cross. UN agencies.

There is a heavy military presence, too. Uniformed men are everywhere; having conversations amongst themselves, joking with two men of the Nigerian Red Cross, and milling around the many displaced people going about their daily lives.

I enter one of the large buildings at the camp and I see that displaced people had carved out sleeping spaces between the heavy machinery that were once used to shape and build bricks.

Maryam is living here with more than 300 other people at the time I meet her. Some, like her, have just escaped from Boko Haram. Others were only steps ahead. They left before the terrorists struck.

Maryam tells me she’s been here for one week and one day. The Nigerian Red Cross won’t let her go yet, not until she gets counselling. That’s the case in this camp for all women who have escaped Boko Haram.

“If you see the first captives that were retrieved to this place, you will cry, because they came out very tattered,” says Manchia E. Andrew, one of the Nigerian Red Cross workers who counsels women like Maryam.

“Some of them, you will see, they will come out without shirts, shoes, or anything whatsoever.”

Maryam tells me when she thinks about the wahala she went through, it sends a shiver through her body. But that’s all. In this place, she sleeps well, she eats well. She says the only thing she needs for her life to fall back into place is to see her parents.

Photo gallery

If she’s worried about anything, it is that Boko Haram will cross her path again.

She keeps saying she’s fine, just fine.

But it’s only been three weeks since her escape.

She avoids eye contact and sometimes just stares into space as she tells me about the last two years.

Click on an image below to read the story