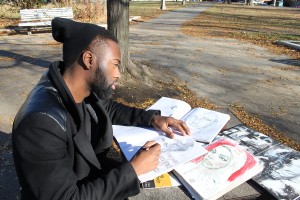

Allan Andre woke up at 6 a.m. on a Sunday morning this past July feeling inspired. He left his bed and made his way to Ottawa’s graffiti-covered Tech Wall at the corner of Bronson Avenue and Slater Street.

There, he spent the day painting a memorial to Sandra Bland, a black woman who died in a Texas jail earlier that month.

Less than 24 hours later, his work was defaced. “ALL LIVES MATTER,” declared the vandal in large, block letters in white paint, covering Andre’s mural.

For Andre, an Ottawa-born visual artist, the vandalism didn’t come as a complete surprise.

“I knew it wasn’t going to last forever,” he says. “Deep down, I wanted to see: Is Ottawa bigger than that? Will they leave it alone? I hoped they’d leave it alone.

“And then they ended up doing it,” he says.

A visible reminder of systemic racism

Andre’s mural depicted a full portrait of Bland, a black woman from Texas who was found dead in her jail cell in Waller County, Texas on July 13, three days after being arrested for allegedly failing to signal a lane change.

While Andre doesn’t consider himself an activist, Bland’s death resonated with him.

“I know Sandra Bland was an activist,” Andre says. “Activists in the community inspired me to say something.”

This includes artist Kalkidan Assefa who worked alongside Andre on the Bland mural. Assefa reached out to Andre in a Facebook post regarding the Black Lives Matter movement.

“All Lives Matter” has been a controversial response to the global Black Lives Matter movement, which began after George Zimmerman was acquitted of the 2012 shooting death of black teenager Trayvon Martin.

Many in Ottawa believe that “All Lives Matter” as a response to the Black Lives Matter movement silences issues that affect the black community. “If you really believe all lives matter, then you wouldn’t write that over someone’s face, [someone] who just died,” he adds.

The belief that Bland’s death is only a concern for the United States indicates that racism in Canada – seemingly more hidden – still goes ignored, Andre says.

“Canada has a history of, ‘Oh, there’s no racism here’,” he says. “It’s sweeping issues under the rug; it’s a way of taking away the voice of people that are disenfranchised.”

Andre says he has been stopped and questioned by police when driving to go see friends in Ottawa, a similar experience to when he lived in Orlando near the home of Trayvon Martin.

Earlier this year, Ottawa Police released 2011-2014 carding statistics which showed 20 per cent of those checked were black, according to news reports. According to Statistics Canada, in 2011, black people only accounted for 5.6 per cent of Ottawa’s population.

Andre says spaces for black voices to be heard seems to be limited, as even street art dedicated to it is defaced.

“I feel like anytime black people try to speak up, a lot of times, people want to mute their voice. Or say ‘All right, get over it’,” he says. “You can’t just come out and say what you want to say without being criticized.”

Dorothy Attakora-Gyan, an instructor at the Institute of Feminist and Gender studies at the University of Ottawa, says it can be difficult to pinpoint tangible examples of racism in cities like Ottawa.

“We often struggle to hear the truth of it,” she says. “We’ve been saying that black communities say the erasure and silencing of our communities is systemic, not just individual.

“It’s more covert. It’s that subtle look you get; it’s that person moving over; it’s the mural being defaced when no one’s looking,” she says.

Attakora-Gyan says defacing or ignoring a voice — even one that presents itself in the form of art — effectively silences a community, a community wanting to be heard.

Black voice needed in cabinet, local writer says

Ottawa native Rachel Décoste, a prominent advocate for diversity, argues it would help to have more black voices in positions of power. She points to Parliament Hill, where Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s new cabinet does not have any black members, despite the election of four black Liberal MPs.

Décoste wrote an article for The Huffington Post in which she criticized Trudeau for claiming cabinet “looked like Canada” when many visible minorities were missing.

“Having a voice at the table, at the cabinet, it’s a psychological boost to know there’s someone there who can speak to your experience,” Décoste told The Junction.

“There are issues that we particularly deal with that are absent from the conversation. Without having somebody in that room, it doesn’t get addressed,” she adds.

She says these conversations must happen at a federal level to elevate the work community activists are doing in Ottawa.

“The activism that happens in Ottawa, or in Canada, it happens from the ground up. It’s the Sandra Bland mural. That’s all we have, because we don’t have another outlet,” she says.