ECT 101

How one psychiatrist embraced an ‘underdog treatment’

Since she graduated medical school in the 1990s, Dr. Lisa McMurray has always strived to be an advocate for her patients.

McMurray points to the landmark Dr. Raphael Osheroff case of the 1980s when explaining the patient-centric approach that has defined her career in the field of psychiatry.

Dr. Lisa McMurray, Clinical Lead, ECT Service at The Royal (Photo courtesy of The Royal)

Osheroff, a medical doctor, became severely depressed after a difficult divorce. His symptoms were so serious that he eventually admitted himself to Chestnut Lodge, a hospital in the U.S. that specialized in talk therapy.

During his seven month stay, his condition got progressively worse. His doctors insisted he continue with psychotherapy, and never prescribed any medication.

In a last ditch effort to treat Osheroff’s condition, his family had him transferred to another hospital, where he was prescribed antidepressants. He recovered within a few weeks.

He sued Chestnut Lodge for failing to treat his condition properly and was eventually awarded a large settlement.

The historic case sparked a debate in the U.S. about psychiatric patients’ right to effective treatment.

It also crystalized Dr. McMurray’s understanding of a doctor’s role as an advocate for their patients.

Early on in her psychiatry career, she noticed that many patients were getting treatments that weren’t necessarily helpful for them.

Doctors were selecting treatments based on their interests, rather than on what would actually help the patient based on science, McMurray explained.

“It really bothered me to see people languishing in different states of partial or non-remission, when we knew there were effective treatments out there,” she said.

It became her mission to ensure that people always had access to effective treatments and it was for that reason that she gravitated to Electroconvulsive Therapy, or ECT.

Despite the fact that ECT is one of the most effective therapies in psychiatry, McMurray said that many psychiatrists still resist providing the treatment, or are scared to offer it.

%

For major depression, ECT is 80- to 90-per cent effective.

%

For treatment-resistant depression, ECT is 50- to 60-per cent effective.

Some doctors see it as a barbaric, archaic, high-risk treatment. Many simply don’t like to do it because it’s done in the early morning hours, which is inconvenient.

“ECT is an ‘underdog treatment’; it’s not very sexy,” said McMurray.

It worried her that an innocent, unsuspecting patient might come into a hospital with a case of depression and never have ECT presented as a treatment option, simply because the psychiatrist refuses to deliver it.

She decided that she wasn’t going to be daunted by the stigma associated with ECT.

“I felt that I owed it to my patients to give them whatever they needed”.

Now, more than 20 years into her career, McMurray remains a strong advocate for ECT. As clinical lead of the ECT service at The Royal in Ottawa, she delivers ECT on a regular basis. She says it’s the only treatment in psychiatry that can so rapidly save a life.

How does it work?

ECT is a form of brain stimulation that uses electrical energy to produce a seizure.

“We run a small current of electricity through the brain, most of it gets absorbed by the scalp and only a very small amount gets to the brain, and what it does is it stimulates the nerve cells so that they all start working together,” McMurray said.

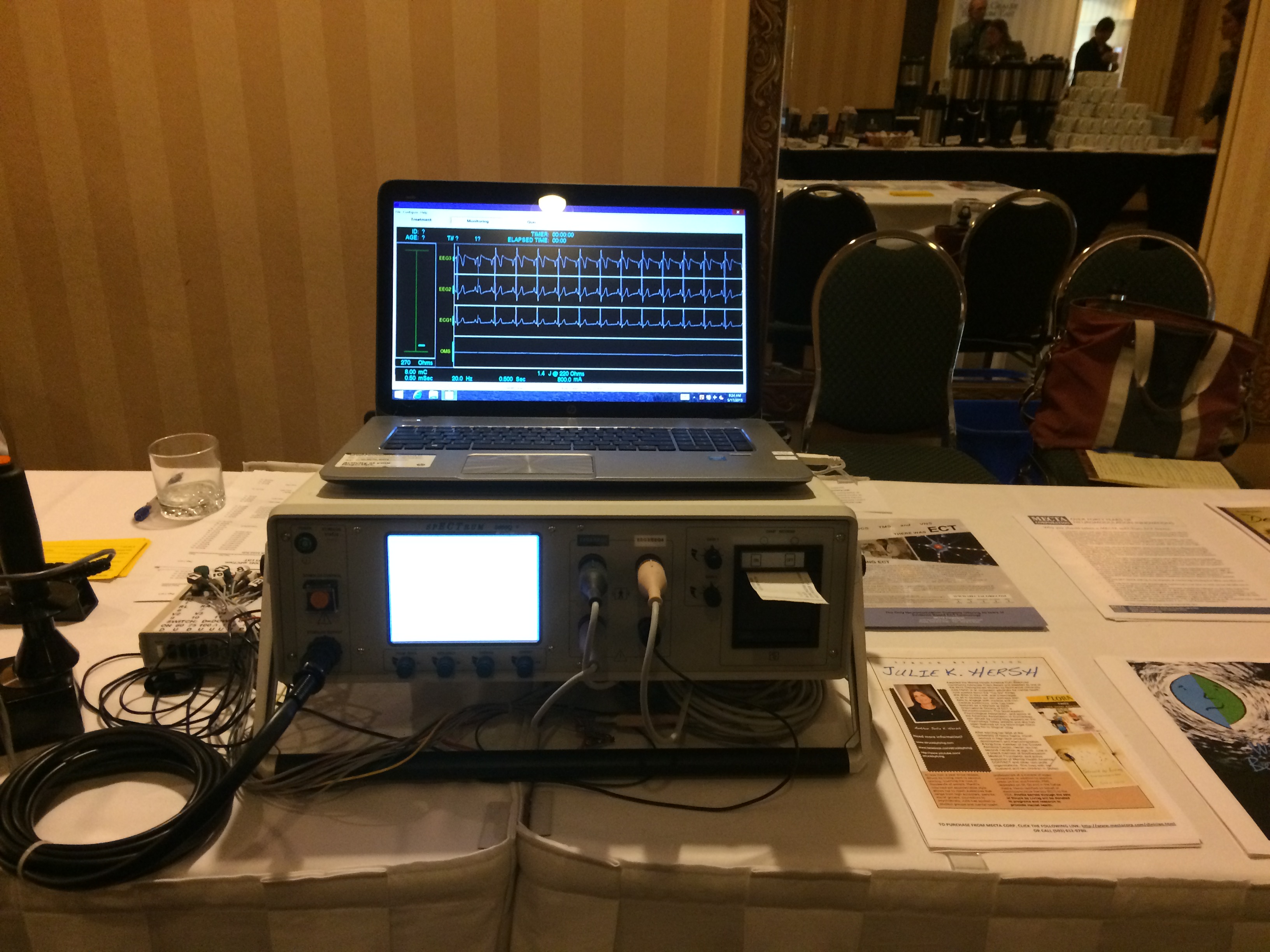

Pictured above is a modern day ECT machine accompanied by a computer, allowing the psychiatrist to monitor the seizure in real-time (Photo © Hayley Chazan)

When all the nerve cells in the brain work in synchrony, the brain produces a seizure.

There is no consensus among practitioners about exactly why ECT works, but there is some belief in the field that the treatment causes a release of chemicals and a change of blood flow, which alter areas of the brain that may be impaired by mental illness.

Controversy

“When I propose ECT to some of my patients, many people are surprised. ‘Are we still doing that? How can you bring that up? I’m sure I’m not that bad.’ It still has a lot of negative stigma associated with it,” McMurray said.

When you consider the history of ECT, it is easy to understand how it got its reputation, McMurray said. In the 1940s and ’50s, before medication, ECT was a very effective and mainstream treatment. But it was also a very dangerous procedure because it was not administered in conjunction with anesthesia and muscle relaxants. These safeguards were only introduced many years later. Without muscle relaxants, the induced seizure would cause convulsions that sometimes broke patients’ bones.

McMurray said that once antidepressants and similar medications were developed, there was a hope in the medical community that ECT would no longer be needed. But ultimately, because of its effectiveness and its ability to work quickly, ECT continued to be used as a treatment for mental illness.

In the 1960s and ’70s, questions started to be raised about whether ECT was over-used or used on the wrong types of patients.

“One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest,” for which Jack Nicholson won an Academy Award, was based on Ken Kesey’s novel, released 13 years earlier. Kesey’s story shined a light on how ECT was used to control and punish bad behaviour, rather than to treat mental illness. This led to widespread mistrust of psychiatry in general and ECT in particular.

Over the next 30 years, with advancements in technology and the endorsement and support from the American Psychiatric Association and the U.S. Surgeon General, ECT once again became mainstream.

Consent and Risk

Although ECT is not a surgical procedure, McMurray said that it requires a rigorous consent process because it involves a general anaesthetic.

“We typically provide patients with handouts and information packages about the treatment and we have to get them to sign a consent form before we can proceed.”

A mother and her son go over the paperwork with the ECT nurse on the day of the treatment (Photo © Hayley Chazan)

Part of the consent process is explaining both the benefits and the risks. Nuisance risks, McMurray explained, include a headache, nausea and some brief confusion after the procedure, most of which can be managed with simple remedies such as Tylenol or Advil. The more serious risks are associated with the general anaesthetic.

McMurray said that for a 40-year-old patient with no medical conditions and a normal body weight, the risks of ECT are very low. An older, more frail person with a history of angina or heart attacks, on the other hand, would be at a greater risk. But what people often fail to recognize, McMurray explained, is that with side effects such as heart arrhythmia, abnormal rhythms and low blood pressure, medication can often be riskier than the ECT treatment itself.

“Overall, ECT is associated with safety and less mortality, but there is a certain risk that something can go wrong in the procedure that is not zero.”

Memory

Of all of the risks and side effects associated with ECT, memory disturbance is the one that most often turns patients off the treatment.

If a patient receives ECT treatments two or three times a week over the period of a month, McMurray said that he or she may have memory lapses about events that happen over the course of treatment.

“A typical thing patients would say to me is, ‘ I know I went for a walk on Valentine’s Day, and I know I was at home with my partner, but I just don’t really remember being there. I know I was there. I know I prepared a meal, but I can’t call up any memories of having been there.’”

Once the patient stops receiving ECT, his or her memory function returns to normal.

McMurray said that in her experience, some patients can suffer from retrograde memory disturbance following ECT. This means that some memories from one or two months before the treatments can sometimes be patchy, although not completely wiped out. Memories that can’t be recalled are usually ones that are not personally relevant, such as a world event or something that happened in the news. However, McMurray has seen some patients lose more significant memories, like an important vacation that they’ve saved up for and have now forgotten.

Because of the potentially serious cognitive side effects of ECT, many people opt out of receiving the treatment altogether. McMurray said that memory disturbance is the reason many psychiatrists save the treatment for patients who have failed other therapies, rather than suggest it as a first-line treatment.

Outpatient ECT

Patients can receive ECT even if they haven’t been admitted to the hospital. This is referred to as outpatient ECT.

For outpatient ECT, patients need to be accompanied by a responsible adult who can take them to and from the hospital and will stay with them for 24 hours after the procedure.

Outpatient ECT is usually done quite early in the morning, before other surgeries.

While the process can differ between facilities, once the patient is called into the ECT suite, the nurse inserts an IV and places monitoring stickers around the head and neck.

“If you’ve ever seen a film like “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” the person is awake and there’s no monitoring,” McMurray said. “These days, we have heart monitoring, monitoring of the oxygen and monitoring of the brain waves.”

Modern-day ECT suites, like the one at The Ottawa Hospital (pictured above), are equipped with heart and blood pressure monitors (Photo © Hayley Chazan)

There are typically multiple medical practitioners in the treatment room: the psychiatrist who delivers the treatment, an anesthesiologist who, in some jurisdictions, may be accompanied by a respiratory technician, and one or two nurses.

McMurray said that once all the monitoring stickers are in place and the patient is completely sedated, the electrical stimulus, which lasts between 20 and 50 seconds, is delivered. The treatment takes no more than 10 minutes — five minutes to get all the monitoring stickers on and five minutes of sleep.

After the procedure, the patient is wheeled into the recovery room, and is usually awake 30 minutes later. Within an hour after the treatment, the patient eats his or her breakfast and is then free to go home under the supervision of a responsible adult.

While a course of ECT can vary between patients, it is usually administered three times a week, typically on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Anywhere between six and 12 treatments can be delivered over a one-month period and, in most cases, patients and their families see mild improvements after just a few treatments.

Maintenance ECT

McMurray said that what makes ECT unique is that unlike other psychiatric therapies, which continue even after the patient recovers, ECT is often discontinued.

One of the major problems with ECT is that while it is extremely effective, almost 50 per cent of patients relapse in the first month alone, McMurray explained.

As a result, she often recommends her patients continue with ECT after they recover from an acute episode, in order to prevent a relapse. This is called maintenance ECT.

McMurray said that there is currently not a lot of data on maintenance ECT and that more research needs to be done to demonstrate its effectiveness.

Electrode Placement

Over the years as ECT has become more advanced and sophisticated, it has also become more complicated. Today, there are multiple kinds of ECT and aspects of the treatment can be personalized to suit the patients’ preferences and values. Dr. McMurray said that one way to customize the ECT experience is through electrode placement.

McMurray said that if the patient is suicidal, isn’t eating or drinking, or if the suffering is particularly severe, bilateral placements, either bitemporal or bifrontal, are most effective, even though they are associated with increased memory disturbance.

On the other hand, McMurray said she’s also seen patients who place greater value on their memory. She said those types of patients aren’t willing to risk losing any part of their cognitive abilities, and instead decide to try right unilateral electrode placement, which isn’t as effective as the bilateral placements, but is associated with less memory loss.

“An important point for patients and families to realize is that it’s not one size fits all,” said McMurray. “You can talk to your psychiatrist and the treatment can be adjusted and modified over time.”

What’s next?

A team of medical professionals in Canada is in the process of creating a set of standards to ensure that ECT is delivered in a high quality, consistent and transparent way across the country. Currently, no such guidelines exist in Canada.

While Dr. McMurray is not directly involved with the push for national ECT standards, she has worked with many of the psychiatrists involved and is supportive of the initiative.

She hopes the standards will help raise the bar for ECT delivery in Canada and will encourage practitioners to administer the treatment in a more sophisticated and personalized way, so that patients get the maximum efficacy with minimal side effects.

“All the benefits and no side effects,” she said. “That’s the holy grail of ECT.”