Learning by doing

On a rainy Sunday morning in January, 16 psychiatrists from across the world gathered in a small lecture room at the University of Ottawa Skills and Simulation Centre.

The largest simulation centre in Canada, “the SIM lab,” is equipped with state-of-the-art medical machinery, fostering hands on educational opportunities for healthcare professionals in all fields of medicine.

With different clinical backgrounds and varying levels of experience, the psychiatrists all have one thing in common, they are determined to increase their skills in the administration of Electroconvulsive Therapy and they hope to do so through Dr. Kiran Rabheru‘s hands-on course.

On this particular morning, most of the SIM lab is closed off, with the exception of about half a dozen procedure rooms towards the back of the facility.

Equipped with surgical exam tables and machines to monitor both the heart and brain, the room is reminiscent of one you would see while watching TV shows such as Grey’s Anatomy or ER.

But one thing is different.

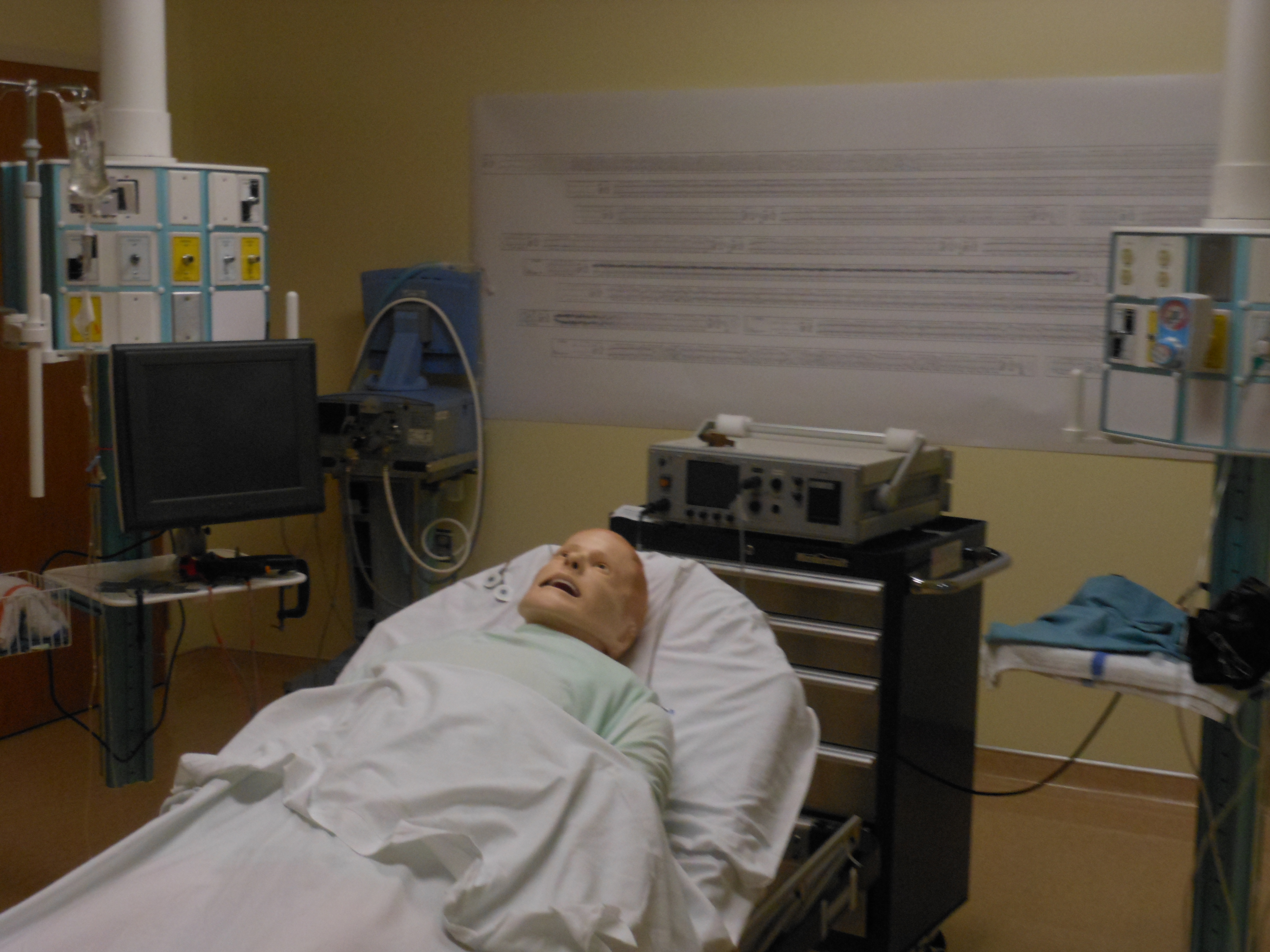

Lying on the bed — as a stand-in for an actual patient — is a life-like mannequin.

Rabheru, a geriatric psychiatrist at The Ottawa Hospital and a member of the CANECTS group, is leading the way when it comes to finding cutting-edge techniques to train psychiatrists in ECT.

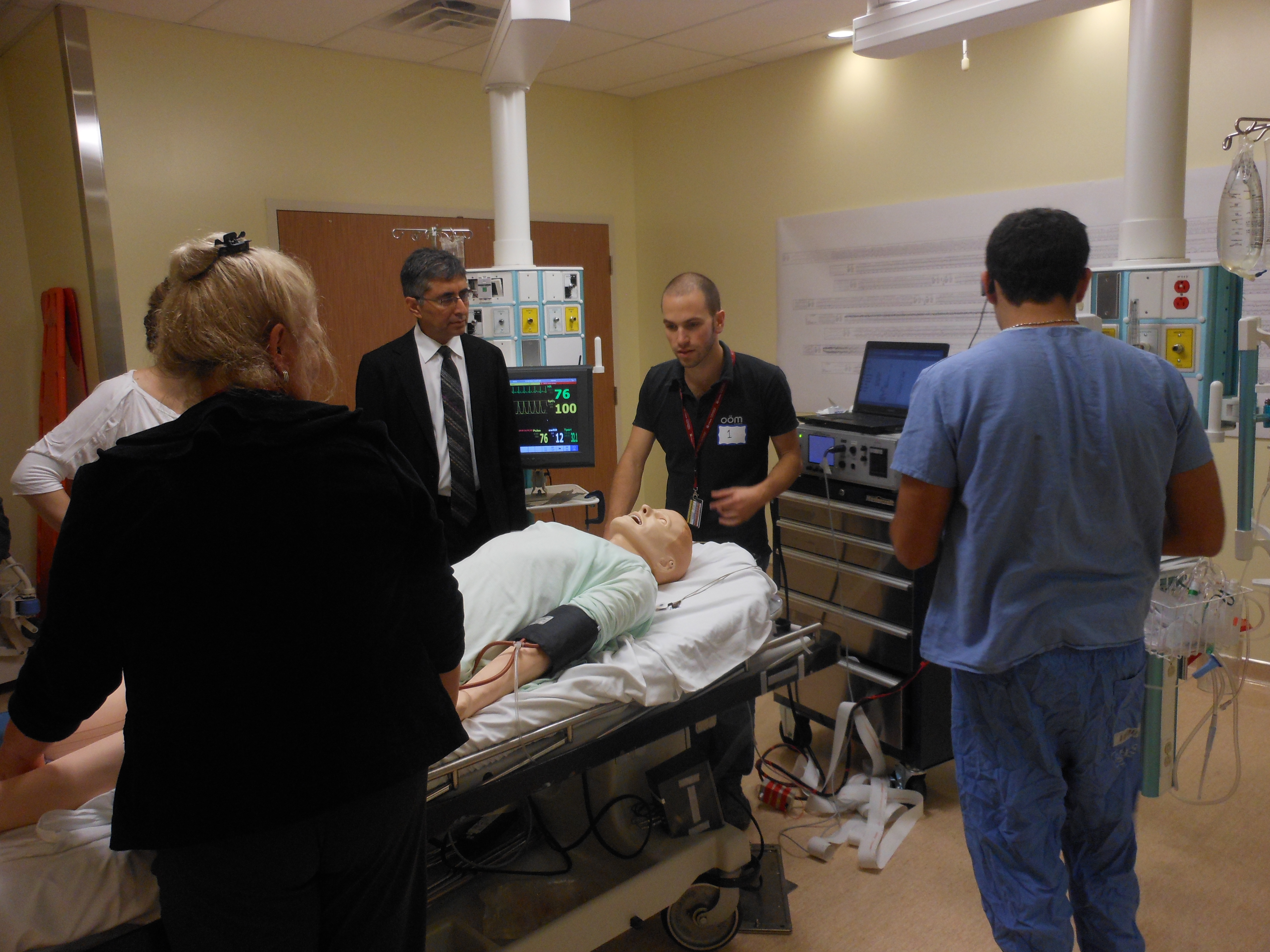

Once every year since 2011, he’s organized a one-day intensive training program in which practising psychiatrists can re-certify their skills in Electroconvulsive Therapy. In addition to receiving lecture-based training, clinicians get to practise administering ECT on state-of-the-art dummies, known as “high-fidelity mannequins.” Rabheru said that to his knowledge, his centre is the only one in the world to offer this type of simulation-based course.

Dr. Kiran Rabheru (centre) accompanied by staff of the University of Ottawa Skills and Simulation Lab (Photo courtesy of Kiran Rabheru)

Trainees practice delivering ECT on high-fidelity mannequins (Photo courtesy of Kiran Rabheru)

A key finding of the 2006 CANECTS survey was that ECT training for psychiatry residents is an area of concern.

The results revealed that more than half of responding centres had no formal ECT training program for psychiatry residents. At the treatment centres that did report offering ECT training, teaching methods varied significantly, with some facilities assigning required readings and others requiring their residents to observe a minimum number of ECT treatments.

Vast variations in training across the country is problematic. Without formal and uniform learning, psychiatrists may not be able to acquire the skills or confidence needed to properly administer ECT. This may discourage practitioners from offering the treatment altogether, and this could result in the underutilization of ECT. Ultimately, the patient would be the one to suffer.

The simulation lab's procedure room looks identical to an actual ECT suite (Photo courtesy of Kiran Rabheru)

A technician sitting behind a one-way mirror controls the mannequin's movements through a computer (Photo courtesy of Kiran Rabheru)

In order to standardize ECT training in Canada, Rabheru is leading the development of a set of standards specifically for ECT teaching. His proposed training standards will be part of a larger document written by CANECTS, consisting of clinical practice guidelines covering multiple areas relevant to ECT, such as treatment and facilities, equipment, dosing, electrode placement, among others. A draft version of the guidelines has been penned, and is currently in the peer-review stage. The hope is that once finalized, ECT centres across the country will voluntarily comply.

Dr. Rabheru said that the training guidelines will stipulate that every person performing ECT should undergo a proper skills-based training course, followed by regular practice of the procedure. Furthermore, a minimum number of annual ECT treatments will be recommended as part of the standards for practising psychiatrists to maintain their skill level, but the exact number has yet to be decided.

While Dr. Rabheru said he’s proud of the CANECTS team’s work, he added that the group unfortunately doesn’t have the authority to mandate ECT training.

He said that if the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, Canada’s national professional association that oversees the education of specialists, adopts CANECTS’ training standards, there will be more support for skills-based teaching in Canada.

One of the responsibilities of the Royal College is to accredit residency programs in medical schools across the country. With the College’s stamp of approval, psychiatry training programs could be altered to require hands on learning for ECT. This would ensure that residents across the country receive the tools necessary to be able to deliver ECT in a high-quality way.

Dr. Rabheru said that the current lack of clear training guidelines means that psychiatry trainees could potentially go through their entire residency program without ever having to administer a single ECT treatment.

The rules for ECT delivery, he said, should be similar to those for any other surgical procedure. For example, he explained that an obstetrician has to do 50 or 100 deliveries per year to be able to maintain his or her privileges.

“While at this point there’s no science behind it, to maintain your bare minimum skills, you need to do at least between 30 and 50 ECT treatments a year, so on average one or two a week,” said Rabheru.

Dr. Rabheru preps the patient for the procedure (Photo courtesy of The Ottawa Hospital)

In today’s operating environment, ECT learning varies depending on where you do your training. For example, Rabheru explained that if you train at a cutting edge centre where ECT is practised in an academic setting, you’ll do book learning as well as hands-on training. In that case, the experience you receive would be no different than training that exists for other surgical procedures in which you learn incrementally and gradually become more independent.

While Rabheru’s own ECT training program at the University of Ottawa follows this approach, many of the smaller centres, particularly ones in remote and rural areas, simply do not have enough resources to be able to offer the same level of training.

In the past, ECT has traditionally been taught using didactic methods, such as lectures and directed readings. Often, a few stations with ECT machines and different equipment would be set up so students could get more of an idea of what a typical procedure looks like. The idea behind this type of training was that students would then go back to their respective facilities and get some practice with real-life patients, under supervision. However, the problem with this method was that no one ever measured to see how effective it really was.

A few years ago, with the help of a team of investigators, Rabheru led the research on this very subject. He split his class of psychiatric residents into two teams and taught half of them using traditional didactic methods and the other half using practical methods in the simulation lab on mannequins. Those who trained with the dummies were allowed to practise their skills for as long as they wanted. After the teaching was complete, both groups underwent a standardized test that measured three different domains: knowledge, confidence and skills. The study revealed that while both groups had an equal level of knowledge and confidence, the group that received the simulation-based training had a much higher skill level. Rabheru said that while none of the traditionally trained residents passed the skills-based station, 100 per cent of the simulation-based cohort passed and actually did very well. As a result, patients of psychiatrists who received the hands-on training had better outcomes and lower risks of cognitive side effects.

This finding is significant, because it rejects decades of assumptions about ECT training. It is also particularly worrisome because it points to the fact that many trainees may have graduated from psychiatric residency programs without knowing how to administer ECT safely and effectively. Patients could potentially be put in harms way if they are treated by a clinician lacking the necessary skills to properly deliver ECT.

“For the first time, we were able to demonstrate that simulation-based training actually has a huge effect on the level of skills, which makes total sense when you think about it,” said Rabheru. “It was nice to see it being demonstrated in a proper scientific trial.”

Rabheru said he’s hopeful that the new training guidelines will encourage other hospitals around Canada and the world to open their own ECT simulation centres and embrace hands-on training.

“People across North America are looking at how to replicate our SIM lab,” he said. “There’s a high level of interest in this type of training.”