Each day, before stepping out into the Florida sun, Hugh Judges makes sure he straps his Fitbit onto his wrist or slips the step tracking device into his jeans pocket.

“Not only do I use it, but I bought one for my lady friend and she uses it too because she’s busy athletically as well,” says Judges. Judges is 80 years old. Hailing from Toronto, Judges spends his winters in Florida. He describes himself as being in good health, besides some “heart stuff” that he sees his physician for from time to time.

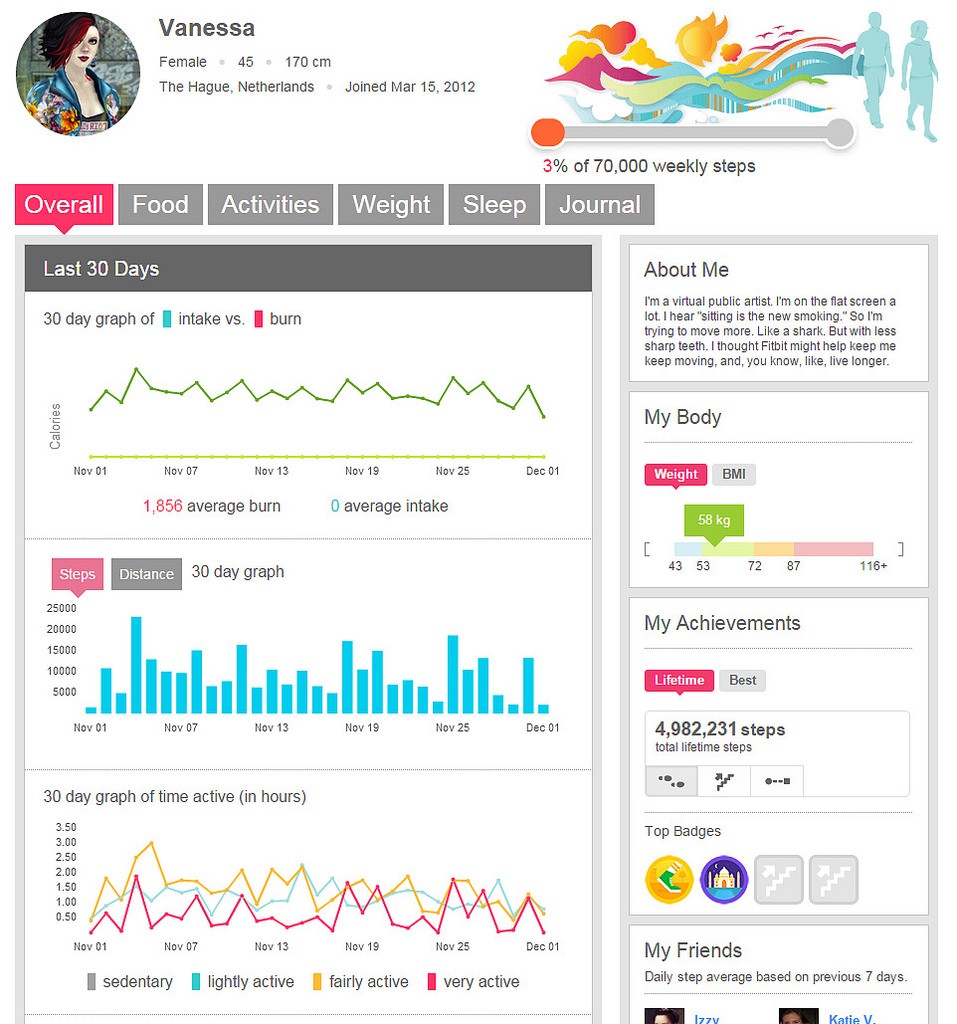

“I picked one up and thought, ‘That’s great’. I can now see what I’m up to,” Judges says of his Fitbit. Not only does he use his Fitbit to monitor his daily activity, but he also sets goals. “I like to say if I get out and about, I want to cover at least 10,000 steps a day or more, and I want to burn at least 2,000 calories a day.”

Judges has been using his Fitbit for three years. The device has become an integral part of his daily routine – so much so, that the 80-year-old would like to integrate more technology into his life. “I’ll tell you what I’m interested in,” Judges says, “I often want to know what my blood pressure is, as a matter of routine.” Currently, Judges drives to the YMCA in his community to check his blood pressure on a machine in the gym. If he doesn’t go to the gym, he has an armband that he uses at home. “But if you had something in hand, or on your arm, that would give you your blood pressure – well sure – it would be a heck of a lot easier.”

The popular Fitbit might well be the first thing that comes to mind for a lot of people whey they first hear “wearable technology.” The heavily marketed Fitbit bracelet tracks steps and monitors calories.

Fitness trackers are undoubtedly the most popular applications of wearable technology. According to the 2014 MaRS Market Insights report Wearable Tech: Leveraging Canadian Innovation to Improve Health, devices like the Fitbit that are marketed for fitness claim 65 per cent of the wearables market. In comparison, non-consumer applications (devices that simply provide healthcare related information) claim only 35 per cent of the wearables market.

Definition

Wearable technology is often synonymous with “mobile health applications.” The Canadian Medical Association defines mobile health applications as “distinct from regulated medical devices, may be defined as an application on a mobile device that is intended for use in the diagnosis of disease or other conditions, or in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease.”

Functions

There are numerous functions of different mobile health technologies. For example, they store and track information, provide periodic information and reminders, contain GPS locators or standardized checklists. According to the CMA, mobile health applications can be used to track fitness activities, to support self-management of health and health information, for post-procedure follow up, viewing test results, and the virtualization of interaction between patients and providers.

These kinds of technologies can be contained in an app in your smartphone. Or they can be a device that stands alone. According to the Canadian Medical Association, mobile health applications are most commonly used on a smartphone or tablet.

The health news publication iHealthBeat estimates that as of this year, 142 million health apps have been downloaded. A study by Pricewaterhouse Coopers states that more than one third of Canadians currently have a mobile health application on a smart device.

Fitness has become synonymous with health and many people have become preoccupied with quantifying their health to improve their own wellness management. The Fitbit and similar technologies like the Nike+ Fuelband collect data handsfree. Originally, they were designed for fitness, to be used by athletes and active individuals. But today, these devices help a growing segment of the population track sleep, calories, and steps. This is the most basic and popular application of fitness technologies and health care.

And increasingly, the focus of developers is on wearable technology that will promote wellness in seniors.

Aging Well

AGE-WELL is a national research network funded by the Canadian government. AGE-WELL is an acronym for Aging Gracefully across Environments using Technology to Support Wellness, Engagement and Long Life. AGEWELL is funded through the government body Networks of Centres of Excellence of Canada. The AGE-WELL program launched in March 2015 and will be funded by the NCE program through February 2020.

AGE-WELL’s mission is to “accelerate innovation” in the field of technology and aging to improve the quality of senior’s lives and produce “economic and social impact” for the benefit of Canadians. Scientists and researchers study the potential of emerging and advanced technologies in such areas as artificial intelligence (AI), e-health, information communication technologies, mobile technologies and policy innovation.

“What we’re trying to do is utilize the potential of modern information and communication technologies to help older people stay independent,” explains Dr. Andrew Sixsmith, one of two Scientific Directors of AGE-WELL. Sixsmith is based at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia, where he is a Professor and Director of the Gerontechnology Research Centre. “So our overall aim is really to firstly provide a wider range of services to help older people remain independent, living in their own homes, although we are also interested in people in all areas like long-term care and assisted living,” states Sixsmith.

As an independent organization, AGE-WELL conducts its own research in the field of technologies for healthy aging. The organization has partnerships among academic, public, private and community sectors.

AGE-WELL also looks at the needs of caregivers because they are the ones who provide a great deal of support to seniors, rather than formal services from healthcare providers. “We have a project which is looking at how we can help caregivers to decide on assisted technology,” explains Sixsmith.

Dan Levitt is the Executive Director of Tabor Village Society, a group of retirement homes in Vancouver. Levitt is pushing doctors, nurses, and home-care staff in Tabor Village to adopt technology in order to provide better care for patients and residents. “There is a movement in the industry to really revolutionize the way things are done, to transform and introduce more digital health into the system,” Levitt says. Levitt has introduced digital schedules and encourages the use of smartphones in his retirement homes. He says that it is on his “TO DO” list to incorporate more technology into the lives of residents at Tabor Village. For example, GPS shoes for his residents with Alzheimer’s.

Sixsmith says AGE-WELL has a number of projects in the pipeline that should help Levitt fulfill his goals.

“We have a number of projects which are in the area of technology development. Those can range from mobility through to helping people to stay connected.” There are other projects that look to innovation and how AGE-WELL can help developers get their project to market. “One of the problems that this sector experiences is that there is a lot of research which is being done, but not enough is getting into the marketplace,” says Sixsmith. “Can we make products easier to use? Can we remove some of the barriers to usage?” These are all things that AGE-WELL is currently investigating.

Andrew Sixsmith describes some of AGE-WELL’s current research on wearable technologies.

AGE-WELL is hosted by the University Health Network (UNH), Canada’s largest research hospital. The UHN, based at Toronto’s rehab centre, is also home of the iDAPT centre for rehabilitation research.

Andrew Sixsmith recommends a tour of the iDAPT rehabilitation centre to see first hand the technologies that are being developed and tested.

Simon Jones is a communications specialist on the Business Management Team at the iDAPT centre. The iDAPT centre is located in the heart of Toronto’s innovation and health hub on University Street. Jones leads a tour through the full service iDAPT research centre which is comprised of 350 scientists, staff, and graduate students. Part of what they do at the centre, Simon explained, is to make their research mainstream. “We want to make our research methods accessible.”

On the tour, which is available to members of the public, Jones visits four labs: the Care Lab, Falls Lab, Home Lab and Climate Lab. These labs are used for simulations. Test subjects are generally volunteers or patients referred to the rehab centre and local hospitals.

Jones also explains the various products and technologies being developed at the iDAPT centre. There are three wearable technologies currently being developed and tested in the simulation labs. One pertains to seniors, one to nurses, and one to care staff.

(These can be explored in the section: Wearable Technology.)

Here are panoramas of the Home Lab, Climate Lab, Falls Lab and Care Lab.

Physicians and wearables

In Canada, health care is provider driven. This means that health care services are delivered to a patient by a registered provider, such as a physician or nurse at a designated healthcare centre. Much like medication or a supervised recovery plan, when a doctor recommends the use of wearable technology, it is prescribed by physicians.

The Canadian Medical Association is among the first national medical associations to provide physicians with assistance in prescribing wearable technology in the form of policy guidelines.

As part of their Ethics and Professionalism, the CMA released Guiding Principles for Physicians Recommending Mobile Health Applications to Patients in May 2015. The document provides basic information for physicians about mobile health applications. It also includes “guiding principles” and the “characteristics of a safe and effective mobile health applications”. The report highlights two very important facets of wearable technology use:

- First, “A mobile health application is one approach in health service delivery. Mobile health applications should complement, rather than replace, the relationship between a physician and patient.”

- And second, “No one mobile health application is appropriate for every patient.” The report highlights recommendations for physicians, such as, “physicians may wish to enter and document a consent discussion with their patient, which can later include the electronic management of health information printed out from electronic management platforms like mobile health applications.”

In addition to the the Canadian Medical Association, the Canadian Medical Protective Association recommends that physicians only select health applications that have been “created or endorsed by a professional or recognized association or medical association.”

The CMA also provides guidelines on wearable technology for patients. Their document Should I use a mobile health application to manage my health? is an easy, four-point guide to using wearable technology. It includes the following four questions: “Are you comfortable with any risks that using the application might pose for your privacy?”, “Is the mobile health application endorsed by a professional association, medical society or healthcare organization?”, “Has the mobile health application been updated within the last year?”, and “Is there a conflict of interest?”

It is vital for both physicians and patients to understand how to use the wearable technology and evaluate when it is appropriate. As the CMA states, not every patient is the the same, and patients may have varying degrees of competency with technology. When implementing wearable technology and mobile health applications in a hospital, these are only some of the considerations that need to be made.

“Clearly this is a growing market,” states Sixsmith.