When Brett Phillips’ study permit expires this November, his plan is to apply for a work permit specifically designed for foreign students who have graduated.

The permit was created in 2008 when the federal government established the Canadian Experience Class (CEC), an immigration stream designed to entice international students to remain in Canada after graduation and eventually seek permanent residence. It will allow Phillips to stay and work anywhere in Canada for three years.

Even though he will have completed his Master of Education studies at the University of Ottawa, this American citizen says he will stay in Ottawa because he likes the city and would like to find work here.

And when the time to apply for his new status arrives, his hope is to find someone to explain how to properly do his immigration paperwork.

But he isn’t sure who that will be since he will no longer be at his university where the international student office normally advises him on many issues, including immigration.

He says he will perhaps ask a Member of Parliament for whom he worked during his internship on Parliament Hill about the right way to arrange his papers or where he can go for help.

On the same campus, Dongni Du – a Chinese woman who is studying accounting at the Telfer School of Management – is also a potential candidate for the CEC immigration stream. She says that when she graduates next fall, she will “work in Canada and maybe immigrate to Canada later.” She says she chose to study in Canada because it has “many good universities” that are “inexpensive” compared to Europe.

Although she knows the work permit she is entitled to apply for after graduation will allow her to stay in Canada for three years, Du says she’s worried it may be challenging to get what she calls a “proper job” in order to qualify for permanent residency.

She has no idea where to go to connect with employers after missing out on a spot in the university-arranged co-op program. That option is now closed because she is no longer registered in enough courses to be eligible.

“I’m looking for internships on my own,” she says.

Her plan for the rest of the time she has on campus is to take advantage of the Career Centre there to improve her presentation and interview skills and to polish her resume.

She hopes the Career Centre will provide her with hiring information after she graduates and will turn to friends to connect her with employers.

“One of my roommates got her job by recommendation from her friend,” she says. “At least networking can give you higher possibilities of getting interviews.”

Both Phillips and Du are planning to apply for permanent residence in Canada after they complete their education, making them typical examples of the pool of the new CEC stream.

But they are also an example of another phenomenon created in the wake of the CEC stream – a group of post-graduate international students who are eligible to apply for permanent residence a few years from now, but are not eligible for much support in the meantime.

For many, it is not clear where they will go for help when they are no longer in school, apart from relying on friends for support.

While the Canadian government touts the Canadian Experience Class immigration stream as a success, some analysts are calling for increased help for foreign students if they are to become Canada’s future citizens.

They also worry that Canada will gradually shut its doors to the world’s poor as it continuously picks its temporary workers and permanent immigrants from among foreign students who are rich enough to finance their education in Canada and foot the bill for their living costs to pursue jobs and permanent residency.

“I think the current federal government has gone in a drastically new direction towards more and more labour market and temporary driven immigration system,” says Sophia Lowe, a research and policy analyst at the Toronto-based World Education Services.

“For international students it’s a bit of a sink or swim mentality at this point and probably will continue to be.”

The Harper government introduced the CEC in 2008 with a mandate to recruit people who are already in Canada and have the Canadian experience through their life and training to stay here permanently. The goal was to deal with the issue of poor performance of new immigrants in the labour market while the need for skilled workers increases with the country’s ageing population.

“This new class will contribute to overall labour force growth by bringing in the talent that Canadian employers and communities need,” the government highlighted in a regulatory impact analysis statement related to the creation of the program.

“Several positive qualitative and quantitative impacts are expected, particularly in terms of improved business competitiveness, reduced immigrant integration costs, and streamlined case processing and client service.”

The statement said applicants under the CEC would have Canadian credentials, which in turn would alleviate the current issue of foreign credential recognition in Canada, which decreases employment chances for many immigrants.

Under the CEC immigration stream, former international students who successfully complete their studies can apply for work permits and stay in the country to work, just like other foreign temporary workers. And one year of work experience in certain technical, professional, managerial, or trade fields in Canada qualifies former students to apply for permanent resident status.

Other temporary skilled workers require two years of work experience in the same occupations.

But Lowe, who says international students are considered the cream of the crop of immigrants, worries that many of them are left to understand immigration processes and employment opportunities in Canada on their own. They also pay their health bills when they are considered potential immigrants and future citizens as a result of the CEC immigration stream.

“Students are seen as distinct from immigrants and therefore they don’t need support in the same way,” she says. “My concern would be for the families of international students as well as other temporary workers, since they are also largely ineligible for services and wouldn’t have even necessarily had the benefit of supports through a university or college.”

Lowe, who wrote a paper in 2011 assessing gaps in settlement services for international students in Canada, recommends that the federal government extend its funding to activities such as explaining immigration procedures and the labour market situation to international students at an early stage when they enter school in Canada or through immigrant serving agencies. She also says foreign students who intend to stay in Canada should be eligible for services like the provincial health care and employment programs, which are normally reserved for Canadian citizens and permanent residents.

She is not alone in urging the government to match its settlement services with the policy shift that has turned Canada’s international students into ideal immigrants.

The Toronto-based Maytree Foundation published a report in July 2009 in collaboration with Queen’s University professor Naomi Alboim in which they warned about the lack of settlement services for former international students.

“If it’s in Canada’s interest on the policy side to see international students as a pool of really high potential permanent residents in Canada, then one would think that a complimentary policy would be to provide the programmatic support that would allow them to integrate fully,” Alboim says.

In this interview, Naomi Alboim talks more about the origins and implications of allowing international students to stay longer or permanently in Canada after they graduate:

For Mohamed Dalmar, who manages settlement services at the Ottawa-based Catholic Immigration Centre, there is no question that international students need help, especially towards the completion of their studies if they are to stay in Canada.

He said his organisation has been serving between 25 and 30 international students every year even if it doesn’t have a budget for them because its programs for immigrants, which are provincially and federally funded, don’t include students until they are approved for permanent residency.

“They need long-term support,” he says. “They need a lot of services like any other newcomers.”

Because they are not eligible for its services, Dalmar says his organisation serves students briefly and avoids going deep into “their problems”. Catholic Immigration Centre is now considering charging them for services like filling forms for immigration and work permits, job-searching, and social support it already offers them if it can’t find a budget to do it for free, he said.

The CEC markets Canada to international students, no evidence it keeps them here permanently

Compared to its initial targets of welcoming 5,000 permanent residents through the CEC in 2009 and a rise to 26,000 immigrants through the program every year by 2012, figures on the number of applications for permanent residence exclusively through the Canadian Experience Class paint a poor outcome so far. Both combined, former international students and temporary foreign workers who got their permanent resident visas by exclusively applying under that category were 2,806 in 2009, 3,930 in 2010, and 1664 until June 2011. Among them the students were 1,583 in 2009, 1,748 in 2010, and 775 until June 2011.

But those humble figures are not what Citizenship and Immigration Canada officials cite when they consider the CEC a success. Instead, they consider that the CEC has also helped former international students and temporary foreign workers to immigrate through many other channels.

“Some candidates may have also been able to apply for permanent residence under the Federal Skilled Worker Program with one year of work experience in one of the occupations listed as being in demand, or with a job offer from a Canadian employer,” said Citizenship and Immigration Canada’s media relations officer Remi Lariviere in an emailed response. “It is also important to note that the Provincial Nominee Programs draw close to 40 percent of their nominees from the same pool of candidates.”

Lariviere said admissions to permanent residency through the CEC are on the rise, an argument he backed up with a preliminary figure of 6,022 immigrants he said were welcomed under the CEC last year. The figure “is within the planned admissions range for the year and a significant increase in admissions of more than 50 percent from 2010”, he said.

Early last November, Immigration Minister Jason Kenney announced that Canada had welcomed its 10,000th permanent resident through the CEC. Though he didn’t say how many among them were former international students, he lauded the program as “one of the Government of Canada’s most recent innovations” and attributed the rise of the immigrants through it to “a substantial increase in the number of student visas issued in recent years.”

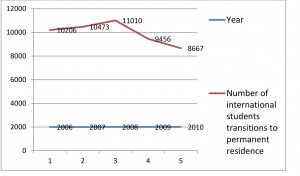

Still, if figures of those who became permanent residents over the last five years are considered, it appears that foreign students’ transition to permanent residence in Canada depends on the economic situation in the country rather than an ease with which they are offered to immigrate through the CEC.

Before the introduction of the CEC, on average, roughly 10,000 former foreign students became permanent residents every year in 2006 and 2007. The number of foreign students becoming permanent residents actually dropped slightly to an annual average of roughly 9000 for the three years (2008, 2009, and 2010) after the policy was enacted.

Given that Canada entered a recessionary economy in 2009, it is likely that the CEC has a self-regulating nature and is dependent on the business cycle, says Arthur Sweetman, a professor in the department of economics at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario.

“The number of people applying (for permanent residence) fluctuates with the state of the economy,” he says. “Of course, this will affect individual students depending on the timing of their study relative to the business cycle (boom versus bust).”

But the possibility to stay longer in Canada after graduation is still expected to make the CEC very popular among international students and Canada a more preferred destination for them.

The increased number of international students in Canada – which has risen dramatically to more than 98,000 in 2011 from fewer than 74,000 in 2007 according to immigration department statistics – is partly attributed to the Canadian Experience Class. For example, the Canadian Bureau for International Education estimated in a 2009 survey that half of the students in university said post-graduate work opportunities in Canada were very important in their decision to study here and almost 3 in 4 in college said the same. The Opportunities for permanent residence in Canada were also very important in choosing to study here, with less than half of university students and 2 in 3 college students saying it was very important, the survey suggested.

And, while figures from Citizenship and Immigration Canada indicate the Canadian Government has been issuing roughly between 15,000 and 17,000 open post-graduation work permits to former international students in Canada every year since 2008, many experts expect these figures to grow even higher as the program becomes better known.

“There is no question that more and more people in Canada are excited about the program and more (foreign) students in Canada who graduate are excited about the program,” says Guidy Mamann, a Toronto-based immigration lawyer who has also been writing a weekly immigration column for Toronto’s Metro News since 2004. “We expect that the approval rate is going to be very high because the criteria are simple to follow.”

Providing education to international students remains one of Canada’s big businesses. A report commissioned by the Government of Canada in 2009 suggested that international students injected $6.5 billion into the Canadian economy in 2008. The dollar value of international students’ contribution surpassed exports of lumber, estimated at $5.1 billion, and coal, at $6.1 billion.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Read more:

Canada’s reliance on immigration for population and workforce growth

Related links:

Staying – and Succeeding: Settlement Service Gaps of International Student Migrants.

Canada First: The 2009 Survey of International Students (CBIE).

Enacting the Canadian Experience Class immigration stream (Canada Gazette).

Statistics Canada’s Population Projections (2009 to 2036).

A ten-year outlook for the Canadian labour market (2006-2015).

Check trends in labour demand and supply in Canada by job type.

Report on international student mobility (OECD).