Art as a bridge

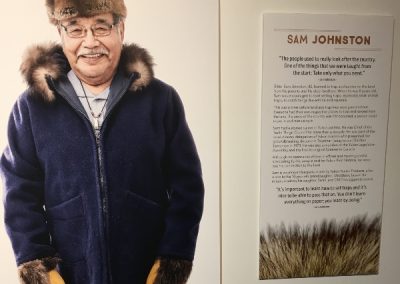

Prominent First Nations community members Peter and Sam Johnston have embraced extra-community outreach to people outside of their Teslin Tlingit Council community, while upholding tradition as shown in their these portraits of their traditional dress. Their images were a part of a portrait exhibit at the Kwanlin Dün Cultural Centre last summer, a collaboration between the Fur Real Project and Archbould Photography.

Below: detail of footwear worn by Sam and Peter Johnston.

[Photos of Peter and Sam Johnston courtesy of Archbould Photography]

As evidenced by Grand Chief Peter Johnston, the contemporary Indigenous person is able to assume multiple identities at the confluence of the worlds they occupy. They can be hunters and trappers at the same time as farmers, artists and university graduates. Poelzer and Coates cite Emma LaRocque’s Defeathering the Indian, in which she declares: “there comes a time when we must recognize each person as an individual rather than as a carbon copy of what we suppose to be his culture.”

This openness to varied approaches will guide communities forward. J.W. McLeod cites Barbra Wakshul when she says that Indigenous leaders “need to know both their own community [values and history] as well as the Euro-American community because they must function in both societies.”

Recent initiatives like the N’tsi wind energy project on Kluane First Nation territory near Burwash Landing, Yukon, were welcomed by all levels of non-Indigenous and Indigenous governments. The ground-breaking ceremony coincided with National Indigenous Peoples Day 2018, and the event was attended by Grand Chief Peter Johnston, MP Larry Bagnell, territorial government ministers and the chief of Kluane First Nation, among other government officials. The turnout of around 100 represented the community’s enthusiasm to generate self-sufficient power and transition into the modern energy economy.

In the last few decades, Indigenous Peoples are increasingly asserting their vision when it comes to sustainably harnessing natural resources from their land. Slowly but surely, the discussion is moving away from portraying the Indigenous population as powerless to settler mandates, and bringing them into the fold as stakeholders. At the same time, the non-Indigenous levels of government (municipal, territorial and federal) know to observe from a respectful distance to allow them to develop at their own pace. With increasing encouragement for First Nations communities to assert their cultural identities, art has emerged as an ideal medium to bridge cultures and keep them relevant going forward.

For those who want to help bridge disparate cultures, immersion gives both parties a chance to warm into each other. Ideally, this takes an extended period of interaction with the other culture’s community.

To go one step further than visible scenes from daily life, Indigenous art is an ideal medium for documenting longstanding traditions. Drawing from centuries of history, art encompasses a wider scope for historical record; on the other hand, Poelzer and Coates have written that Western historians tend to document culture using a rules-based approach. When the same approach is applied to documenting First Nations culture, this may come across as overly rigid for a comparatively intuitive culture.

Similarly during her research in the 1970s and ’80s, anthropologist Julie Cruikshank questioned her recording methodology: for First Nations knowledge-keepers, does a written account represent the raconteur’s nuances as effectively as a live storytelling session? Her takeaways indicated that unlike written work, oral storytelling does better in preserving individual talents, interests and styles of their raconteur – much like the community service spirit of their art, Cruikshank notes that no oral account is better or less correct than another.

Cruikshank said in her book, Life Lived Like a Story: “by ordering it this way [written out], I am inevitably interpreting what the subject has chosen to pass on to me.” She continues: “Attempts to sift oral accounts for ‘facts’ may actually minimize the value of spoken testimonies by asserting positivistic standards for assessing ‘truth value’ or ‘distortions.’”