The financials of arts supports

Creating, Knowing and Sharing:

A national funding model for First Nations artists

‘Creating, Knowing and Sharing: The Arts and Cultures of First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples’ was launched in April 2017. The initiative is the Canada Council’s contribution to ongoing efforts toward reconciliation involving Indigenous and Canadian cultures.

Since its inception in 1957, the Canada Council’s attention to inclusivity has been precedent-setting for other countries. Before then, however, Indigenous culture was suppressed by settlers since Jacques Cartier: among his priorities was converting Indigenous Peoples to Catholicism through musical indoctrination. Art was an important import to the New World from France, a system that successive settlers propagated. In the mid-’40s and late-’50s, it was the British Canadians who cultivated the values of European high society, as ‘Canadian art’ was deeply-rooted in antiquated streams like music, dance and theatre.

As Canada approached its 100th birthday, the need to assume a distinct national identity grew, especially as Canadians refused to act as cultural imitators to Britain or America. The Massey Report was commissioned to collect data on the state of the arts across Canada, heralding a new chapter in self-sufficient artistic creation in 1951: “what was lacking in Canada was not talent but the infrastructure to create a viable, cohesive artistic and literary community, such as existed in European countries.” The report proposed the establishment of a national arts funding body, hence the creation of the Canada Council for the Arts in 1957.

In 1968, newly-elected prime minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau enacted a national Arts and Cultural Policy, further advancing the Indigenous arts agenda: one of its mandates was to “stimulate the two founding cultures and to integrate the original contribution of the native peoples [sic] and New Canadians.”

In 1994, the Aboriginal Arts Secretariat was established at the Canada Council. By 1998, enough funds were raised to begin supporting Indigenous artists, setting the stage for the launch of ‘Creating, Knowing and Sharing’ in April 2017. The program is aimed specifically at Indigenous artists in support of their communities’ artistic and cultural activities: for the fiscal year 2017 to 2018, the program distributed $9.4 million to Indigenous artists out of the Council’s total $202.7 million in distributed grants; by 2021, the amount is projected to increase to $15 million, according to the Council’s Director of Indigenous Arts, Steven Loft. He says the Council has been gradually increasing funding to Indigenous arts over the years; prior to Creating, Knowing and Sharing the total amount that went to indigenous artists and organizations came to a little over $5 million.

In a promotional video for the program, CEO Simon Brault emphasizes that the Council’s mentality for Indigenous arts heritage has always been grounded in social obligation and awareness, as opposed to that of financial need – he did not, however, back up this statement with an example. Brault also affirmed that reconciliation had been a key motivator for ‘Creating, Knowing and Sharing’ well before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission report put forward a recommendation for Canada’s national arts funding body to lead by example in Indigenous artistic reconciliation.

In January of this year, the director of Indigenous arts at the Canada Council for the Arts thought back on the impact of ‘Creating, Knowing and Sharing’ as it neared the end of its second year of operation.

Next steps include stepping directly into northern communities to explain their funding offerings. In early February, the Council visited Whitehorse and Dawson City for their artist outreach, meeting with interested artists one-on-one to explain their funding programs. Loft says that program officers try to target underrepresented communities.

“In the north, certainly when we talk about regions where we do have that geographic disparity, many issues are true in the Arctic as in the Atlantic – just travelling in this land poses challenges,” Loft says. The Council’s goal is to identify communities that are not aware of assistance. “Where are the artists that are NOT applying to us? That takes more strategic work – that’s why we like it when people invite us, ‘We have a thriving arts community here you might not know about.’”

In response to concerns about accessibility of the application process, as raised by grant recipient Teresa Vander Meer-Chassé, Loft says that the Creating, Knowing and Sharing team has done “a lot” of focus group work to write at the appropriate language level as well as to make it “relatable to their everyday craft” based on applicant feedback. “I’d argue very much that the language in the old funding model was really, very difficult, and we went through a plain language exercise in developing the new model,” Loft says. “The difference is quite profound.”

Loft has a message for people who cast doubts on the program’s effectiveness. “I’ve heard them all, they generally fall down,” he says. “This is not about being a special interest group; this is about respecting the nation-to-nation relationship, respecting treaty rights, respecting inherent Indigenous Peoples’ rights,” citing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples and the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

He brings his Mohawk identity into the conversation: “As the First Peoples of this land, we’re also in a treaty relationship with the nation-states. These are rights-based – this has nothing to do with giving one group something to make them happy or because they’re loud; this is a rights issue. Our cultures are distinct to us, our arts and cultures are distinct to that relationship. By creating this program [Creating, Knowing and Sharing], we honour that relationship.”

“Are we on a path of decolonization? I would argue very much yes,” Loft says. “We are a small federal agency, but my hope is that that becomes more of the journey.”

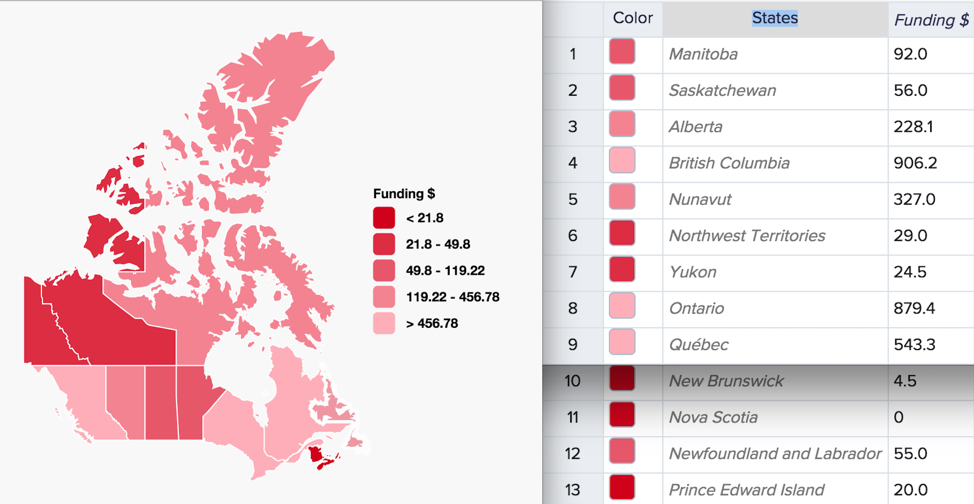

Indigenous arts funding allocations across Canada by the Canada Council for the Arts in 2016-17, the final year before the implementation of ‘Creating, Knowing and Sharing.’ Funds were administered through the former Aboriginal Arts Office. [Graphic by Jennifer Liu using Piktochart]

Steven Loft and Simon Brault are important executives at the Canada Council for the Arts involved in implementing the ‘Creating, Knowing and Sharing Indigenous’ funding stream. [Photo courtesy of Canada Council for the Arts]

“We can acknowledge the self-determination and sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples and by doing that, we can say we’re going to create a program that’s based on that, because it can’t be based on the same things that the other programs are based on, because that’s the colonial experience.”

Yukon Government: The territorial arts funding body

In his Yukon Government office, Doug Bishop helps make important funding decisions for First Nations arts initiatives. The crux of his role involves assuring funding for First Nations cultural centres in the territory, as well as for projects earmarked for Yukon First Nations.

Being of Cree-Métis background, Bishop strives to uphold fair funding decisions. Previously, his Cree-Métis background helped him in his executive role on the Yukon Métis First Nation executive. Since 2012, Bishop has been the First Nations Heritage Advisor in the Department of Tourism and Culture.

Yukon Government Arts Section funds up to 10 per cent of some cultural institutions’ annual budgets. Bishop says they give out about $450,000 in project money each year, plus a few million dollars in operations and maintenance. For the other 90 per cent, Bishop cites the Community Development Fund as being a significant source of supplementary income.

Bishop and his boss are part of a three-person panel that reviews and scores applications. Ultimately, the trio don’t decide on who gets the funding – they only write transfer payment agreements. That said, panel participates in discussions with representatives from museums and cultural organizations on funding allocations. Funding is distributed from the top score down until all the money is assigned. There are pools for Travelling artist, Special projects, Museums contribution program, and Canadian Heritage. It is an annual procedure.

And yet, Bishop says that in the late ’80s or early ’90s, it was this very department that opposed government funding for cultural centres.

“At one time, there was a real sense of purity with museums programs, and art was not considered to be museums-related,” Bishop says, explaining funding propositions would have been “thrown right back” at him.

He recalls one Museums Unit meeting where the discussion was on acquiring an artifact bequeathed by First Nations elders via their families.

“ ‘We’d like this to be in care at the cultural centre, so it lasts a long time or forever,’ ” Bishop recalls the family’s words.

The delegates were against accepting the family heirloom, saying that the object was “not good enough, or you just can’t take stuff from everybody,” to which Bishop replied, “‘Well it doesn’t work like that culturally – you can’t be employed at a First Nation and start turning away people’s favourite ancestors at the counter because there’s something that you don’t feel that you need.’”

But the funding model has changed with time: in the last few years, his team has secured funding for more projects and exhibits that represent First Nations art.

Bishop thinks of his role as a middleman between government and First Nations communities, raising cultural sensitivity and bridging distinct cultures. Bishop admits that when relaying a message on behalf of First Nations to the government, “sometimes it’s a really rough ride” to carry out the communities’ wishes. “That’s not always an easy sell in government – in government there’s a lot of rhetoric about inclusion and valuing, for some people that’s all it is; it’s all rhetoric – it’s not something they practice or believe in.” He adds, “So it makes it hard sometimes to get things done.”

Tokenism is something Bishop has seen the Yukon government resort to. “They want to put their Indigenous people up front when they go to a trade fair or an event, so they’re seen to participate,” he says.

That makes it difficult for government to be seen as genuine to First Nations clients. “Cause you’re working against this reputation a lot of the times, there’s this idea that you’re just here to put out the official line,” he says. “That’s not healthy.”

Ultimately, Bishop hopes the funding will bear fruit in restoring and validating Indigenous cultural identity.

“The funding that we issue, you’re not going to THRIVE on that much money, but you can keep the doors open and you can offer something [to First Nations groups]…how you go about that is more their choice than ours.”

The Yukon Government Department of Tourism and Culture is housed inside the Yukon Visitors Information Centre in downtown Whitehorse. [Image courtesy of Google Maps]

“Culture is all together; in government we tend to put everything into its silo and have it neatly organized, and that’s not how other people see things.”