Self-reflections

One year ago this month, I decided to take the plunge and spend part of my summer in Yukon to study Indigenous arts and culture first hand.

What set me out on this path was acceptance into the Stories North experiential course, organized by Kanina Holmes under the Carleton University banner. A little birdie (I’m sorry for not remembering who) suggested that I translate my experiences into an MRP research topic.

I hesitated to combine these two academic tracks. First, there was the intimidation of double work load in what I’d heard was an internet-poor region, if not described as wilderness and without the resource density as in southeastern Ontario. Then there was the thought of not being able to take in what was described as Yukon’s natural beauty.

Finally, I took on a two-week internship at a Whitehorse-based Indigenous arts and culture magazine prior to Stories North. As it turns out, my work and explorations consistently fed into one another as I kept on encountering familiar players in the arts and culture scene. The arts world is a small one, especially in Canada’s North, and the experience was rewarding to experience even more so than to document for future reference.

Before boarding the plane to Whitehorse, I researched the existing knowledge bank on Yukon, Indigenous Peoples and reconciliation in Canada. The cultural gaps became apparent, with Conrad Black characterizing Indigenous Peoples’ cultural lifestyles as “There were some impressive native ceremonies, and remarkable skills, but it was, despite much subsequent romanticization, a very primitive form of society,” or “It is fair to say that the Indians were capable people of much promise but that their civilization, though exceptional in some arts, crafts, and in physical prowess, was uncompetitive with much of Europe for the preceding two thousand years,” or to exercise his full right to free speech, “Indian society was not in itself worthy of integral conservation, nor was its dilution a suitable subject for great lamentations.” It quickly became evident that experiencing a situation first-hand is critical to understanding the contemporary situation of events such as the state of First Nations culture in our time.

Covering First Nations culture involved special care and awareness as a visitor from outside their community. I had the good fortune of spending eight weeks at various cultural events in Yukon, and I was pleasantly surprised to be warmly welcomed into the circles of First Nations communities, free to observe their activities on the side, and to approach them after the events’ conclusion with any questions.

Because of this level of access, I encountered raw moments of emotion in my interactions. I had my first-ever interview where the subject shed tears over past memories on his personal journey to reconciliation. The question of what events were appropriate to use in my project also came into question, and one community required the a media authorization form to be completed before I was granted permission to interview community members.

There were special considerations that deviated from standard journalistic practise, given the nature of working with First Nations people. Specifically, certain subjects mentioned their understanding of our interactions as collaborative partnerships and that they would appreciate being able to review drafts before publication. I decided to deal with each request on a case-by-case basis, in consultation with my MRP advisor. Often, I found that describing my project in a follow-up phone call would satisfy their desire to understand my framing, as opposed to dictating the exact vocabulary to use.

As much as possible, I strived to preserve my interview subjects’ original message through their own media clips as opposed to paraphrasing them in written form. The progression to overcoming hardships and reaching solutions is most wholesome when told from the perspective of somebody born into a culture that has lived for millennia off of the land, as have Yukon First Nations groups.

Between First Nations communities and individual members, art then is quietly commanding renewed public attention. It is a healing force for past economic, political and land-rights injustices, and is looking to become an active instigator for change in the hands of certain young First Nations advocates.

My hope is that this multimedia project has helped to raise awareness of Yukon’s cultural vibrancy without introducing interference in the movement. In the words of Gilbert Adair in Surfing the Zeitgeist, “The purpose of journalism – the purpose of an article, let us say, on the arts – is surely to draw the reader’s attention to an achievement which might otherwise remain neglected or misunderstood, which at any rate calls for some significant degree of interpretation, in the hope that the same reader will then be tempted to explore it further for himself.”

Politicians and cultural actors alike are doing their part to keep the traditions of Yukon First Nations groups alive. Combined with rising attention from other jurisdictions, culture looks to provide a softer approach, but still a significant contribution to reconciliation moving forward.

Dream catcher at Long Ago Peoples’ Place [Photo © Jennifer Liu]

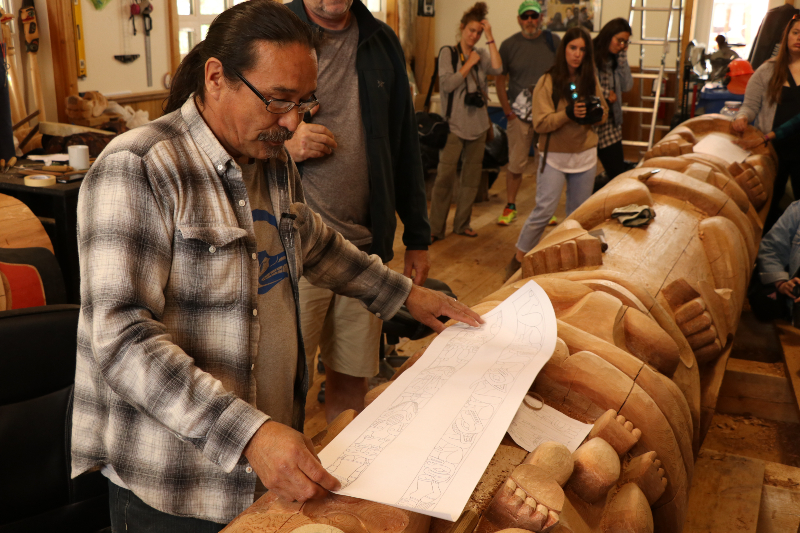

Tlingit carver Keith Wolfe Smarch shows the Stories North students around his studio. [Photo © Jennifer Liu]

Moosehide Gathering [Photo © Jennifer Liu]

A carver’s work at Atlin Arts and Music Festival 2018. [Photo © Jennifer Liu]