E very few months Breanne Littley cleans out her closet. Unwanted, outgrown or damaged childhood toys, old comforters and clothes are stuffed into black plastic garbage bags. She piles the bags into the back of her car and drives them to the closest Value Village or Goodwill.

In North America donating clothes is popular and encouraged by cities like Toronto and Markham and provincial non-profits like the Recycling Council of Ontario for disposing of unwanted clothes. Littley is part of the 76 per cent of Canadians who donate their unwanted clothes and other household items to charitable and non-profit organizations, according to a 2015 report from Statistics Canada that studied charitable giving by Canadians. Despite this statistic, textiles continue to end up in landfills.

It’s difficult to determine the amount of clothing that ends up in landfills in Canada as there are no statistics available. In comparison, a 2009 waste study conducted by the Environmental Protection Agency found that 21 billion pounds of textiles ended up in landfills in the U.S. The Council for Textile Recycling, a non-profit based in Maryland, projects the amount of textile waste to rise to 35 billion pounds in 2019 due to mass consumption.

After the City of Markham introduced a clear-bag policy for household garbage, Claudia Marsales, senior manager of waste and environment management, said they were surprised to see not only the number of textiles being thrown away, but the types of textiles.

“What we found through the clear bag system was there was a lot of textiles in the garbage and we are talking about brand new running shoes, coats and bedding,” Marsales said.

With the increasing pressure on city garbage disposal, the City of Markham came up with another strategy to reduce the amount of household waste going to the landfill. It banned residents from putting textiles in the garbage. Instead residents can donate their unwanted textiles, including holey socks, stained t-shirts and old jackets to city-run donation bins to be recycled.

The textiles are collected from the bins by the city’s charitable partners: The Salvation Army, Diabetes Canada, and STEPS to Recovery. The donations are sorted to determine if they are suitable for re-wear, reuse or recycling. The majority of the clothes are sold to Value Village. The donations that are damaged or unsuitable for reuse are destined for the landfill while a small fraction are recycled into new materials such as insulation or stuffing for car seats. According to Jo-Anne St. Godard, executive director of the Recycling Council of Ontario, there are minimal alternatives for diverting clothes from ending up in the landfill because of the limited ability to recycle clothing materials in Canada.

St. Godard isn’t aware of any “recycling with respect to re-pulping the fibres down to their original state and then reweaving for the use of making new textiles into clothing,” happening in Ontario or even globally on any sort of scale.

This medium sized business buys rags in bulk. The rags are old t-shirts. (Photo courtesy of Josephine Abate)

Textile collection a ‘massive revenue generator’

The collection of textiles is an important business model employed by charities to generate a good chunk of their revenue. Diabetes Canada along with other registered Canadian charities rely on selling the donations to Value Village to help pay for programming such as research and education. With more than 142 stores across Canada, Value Village, also known as Savers in the U.S., is one of the biggest for-profit thrift sellers of used clothing and unwanted household items. Every year Value Village pays Diabetes Canada $10 million for items it collects. The textile collection business alone represents one-quarter of Diabetes Canada’s annual revenue.

“It’s a massive revenue generator for us, in terms of contribution to Diabetes Canada,” Scott Ebenhardt, director of business development with the National Diabetes Trust, said.

Diabetes Canada sells the donations to Value Village because unlike other charities such as Goodwill and Salvation Army, it does not operate retail stores.

“All of the charities are really good at collecting but we put the burden of sorting, grading and reselling on to Value Village,” said Ebenhardt.

They do this because of the costs associated with running retail stores. Ebenhardt doubts that another thrift player in the market could handle the 100-million pounds of donations they send to Value Village every year.

A donation bin for Canadian Diabetes sits outside of Value Village in Ajax, ON. (Megan McPhaden)

Where do your donations go?

From the moment clothes are donated to a charity or for-profit they begin a complex journey that could take them out of the country, across borders and over oceans. Clothes follow different paths and final destinations, because they are sorted and graded based on a number of characteristics including quality, type, size, gender and age group. The destination is also determined by the business model of the charity or for-profit. For-profits like Value Village rely on selling their excess donations because it is only able to sell approximately 20 per cent of the items put onto the retail floor.

Of the items that are unsold, the textiles that are considered wearable, are sold in large bales to different resellers of used clothing. For example, they could be purchased by graders who sort the clothing for export to overseas markets in Central America, South America, Africa and Eastern Europe.

Littley, like Nayak, says she was neither aware that her donated clothes could end up in developing countries in East Africa and other parts of the world, or that the clothes have negatively impacted domestic textile industries in developing East African countries.

Back on the streets of Arusha, Tanzania, used clothing bears the telltale signs of the organizations that the clothes were donated to; Goodwill, Value Village and other charity and for-profits tags are still attached. These clothes were originally donated by Canadians, Americans and other citizens from wealthy Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. The global second-hand clothing market is valued at $2.4 billion, according to UN Comtrade data. In 2016, Canada was the seventh largest exporter of used clothing.

Goodwill, Value Village and British Heart Foundation tags show the past homes of these clothes for sale in Arusha’s Central Market. (Megan McPhaden)

The EAC represents one-quarter of the global reuse market for used clothes exported from the U.S. and Canada. The EAC blames second-hand clothes imported from the United States, Canada and other OECD countries for both inhibiting the growth of and destabilizing domestic textile industries in their countries. In 2015, the EAC responded by jointly agreeing to restrict imports of second-hand clothing by 2019 by increasing tariffs and potentially banning clothing imports entirely.

Reducing our reliance on selling used clothes to overseas markets

Reuse is the primary strategy for diverting textiles from going into the landfill and is partly driven by the profitability of the industry. As the import countries of second-hand clothes turn towards protecting their own textile and apparel industries and shun second-hand clothes, Jo-Anne St. Godard, executive director of the Recycling Council of Ontario, indicates that this could seriously disrupt the business models of reuse organizations like charities and for-profits.

“Generally, what happens with commodity markets when exports are interrupted, they generally try to find new recipients and I think the same is true for reuse clothing,” she said.

If exporting to overseas markets was to become unaffordable or if these overseas markets no longer allowed second-hand clothing to be imported, the majority of second-hand clothes would end up as waste in North America as the value of the clothes would reduce dramatically and the demand is low.

Recycling is one alternative, however in Canada only a very small percentage of clothes are able to be recycled and turned into new products such as car seat stuffing and cloth. The process of breaking down fabric is complicated by garments that are created using mixed materials like jeggings that are woven with cotton and spandex.

Due to the lack of infrastructure and limited technology in Canada and the U.S., we are unable to recycle the volume of textiles that are disposed of every year. New technologies are however being developed. In September 2017, clothing-retail giant H&M and partner Hong Kong Research Institute of Textiles and Apparel (HKRITA), announced a breakthrough in creating technology that can successfully separate blended textiles and turn them into new fabrics and yarn. HKRITA plans to release the technology so that it will be commercially available.

From Claudia Marsales’ perspective, Canada needs to develop the textile recycling industry before it can stop exporting used clothes.

“We need local industries for the recycling of the textiles or we have to stop consuming so much,” she said.

Her solution is getting the Ontario Ministry of Environment and Climate Change (MOECC) to classify textiles under the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR). This strategy places the burden of recycling the clothes on the producer by integrating environmental costs associated with the goods into the retail price. The OECD describes EPR as “programs characterized by the continued involvement of producers and/or distributors with commercial goods at the post-consumer stage.”

However, St. Godard says the EPR approach is challenging to apply to textiles because the life span of clothing varies since clothes may sit in your closet for months, years or even decades.

“The other issue is the fashion industry changes very, very quickly,” she said.

“There are companies that go out of business, there are companies that get bought out by other companies. So, legacy issues need to be thought through.”

This complicates the ability of the province to hold companies responsible for recycling and disposal.

In the past, EPR was used as a solution to the issue of toxic electronic waste like from old computers and refrigerators. Consumers had next to no ability to recycle these items apart from disposing of them in landfills or at depots. Often this e-waste from North America was offloaded to developing countries where “crude and inefficient techniques were used to extract materials and components,” causing environmental catastrophes in Agbogbloshie, Ghana and Guiyu, China, according to a 2014 report from United Nations University.

The City of Markham has been pushing the MOECC to categorize textiles under Ontario’s EPR, however there has been pushback from retailers.

“Companies don’t necessarily like EPR,” Marsales said.

Currently producers of clothing have no financial responsibility for recycling t-shirts and other articles of clothing at the end of their life. EPR would make the “fast-fashion manufacturers responsible for looking after the life cycle of the t-shirt from manufacture to end-of-stream,” she said.

Another factor St. Godard says needs to be considered is, if there is no recycling industry here in Canada, what will the money generated from introducing an EPR be used for?

“Is it mitigating landfill costs? Is it to develop a recycling industry? That for the most part doesn’t exist,” she questioned.

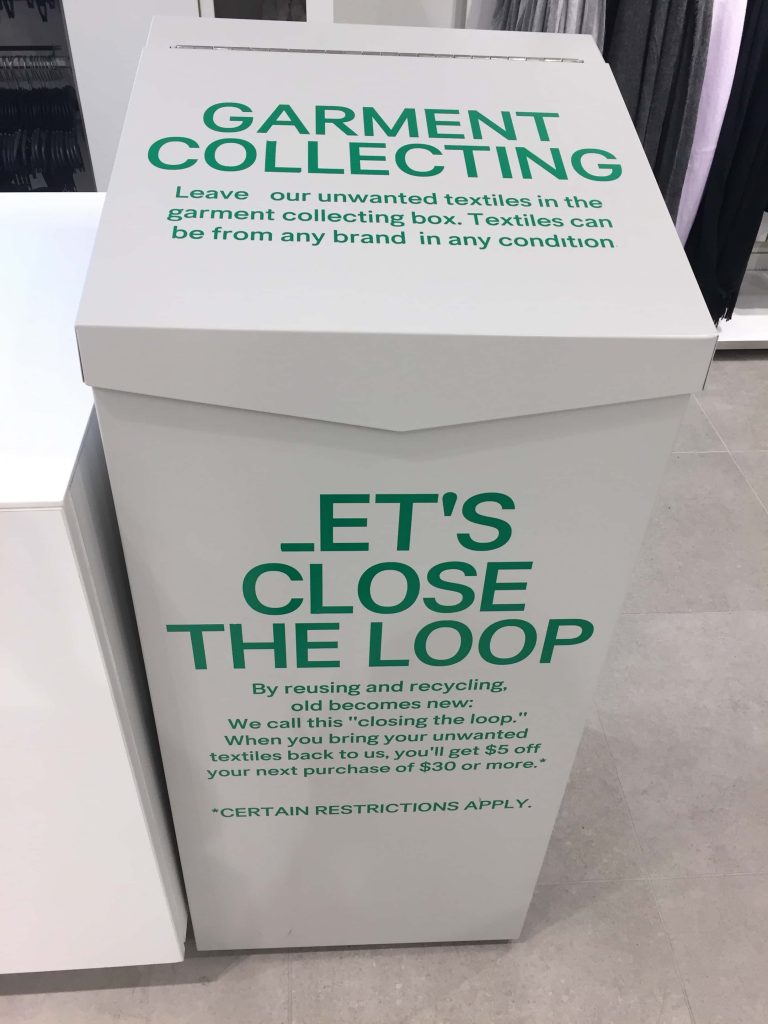

Some retailers like H&M are introducing garment collecting initiatives known as closing the loop by incentivizing consumers to bring their unwanted and used clothing to the store in exchange for a discount or store credit. The majority of these clothes are sold for reuse; some are recycled, and the remainder that are unusable are sent to the landfill.

A garment collection box is shown inside an H&M store in Pickering, ON. (Megan McPhaden)