T extile and apparel industries in Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda continue to struggle to keep a foothold and grow. Each of these countries has experienced a decline in the number of textile and apparel manufacturing facilities in operation. Since the late 1970s, the decline can be attributed in part to geopolitical and ethnic clashes ranging from the Rwandan genocide to the Ugandan-Tanzanian war.

These issues caused political and economic instability that disrupted industrial production for domestic and international markets. During these crises, second-hand clothing was imported by international aid agencies to provide local people with clothing. Eventually after these economies were able to recover these clothes were no longer imported as a form of charity. Instead they have become a for-profit business of reusing clothes and imports have been steadily increasing.

In Unravelling the Relationships Between Used-Clothing Imports and the Decline of African Clothing Industries, David Simon, professor of development geography at Royal Holloway University of London, offers another reason for what has prevented East African countries from achieving global success in the textile and apparel sector.

Simon and co-author Andrew Brooks point to a combination of factors including economic liberalization policies like the Agreement on Textiles introduced in 1994 and the removal of the World Trade Organization’s Multi Fibre Arrangement (MFA) in 2005 that eliminated quotas on the amount of textiles, clothing and fabric that developing countries could export to developed countries. The removal of the arrangement was intended to expand developing countries’ access to markets in developed countries.

Instead it benefited the countries with large and highly developed textile industries and smaller less sophisticated industries were left out in the cold. Following the removal of the MFA the global textile and apparel trade faced tremendous competition from China and many developing African countries’ textile and apparel industries were squeezed out. Textile and clothing industries in EAC countries were ill-equipped technology and infrastructure-wise to be competitive, Kenya being the exception.

Kenya is the leading exporter of new clothing to the U.S. under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), a preferential trade agreement between the U.S. and sub-Saharan African countries that gives them preferential trade access to the U.S. market. Under AGOA, in order for countries to maintain these benefits they must eliminate barriers for U.S. trade and investment.

In 2015, Kenya’s top exports to the U.S. were woven and knit apparel totaling $368-million USD, according to data from the United States Trade Representative (USTR).

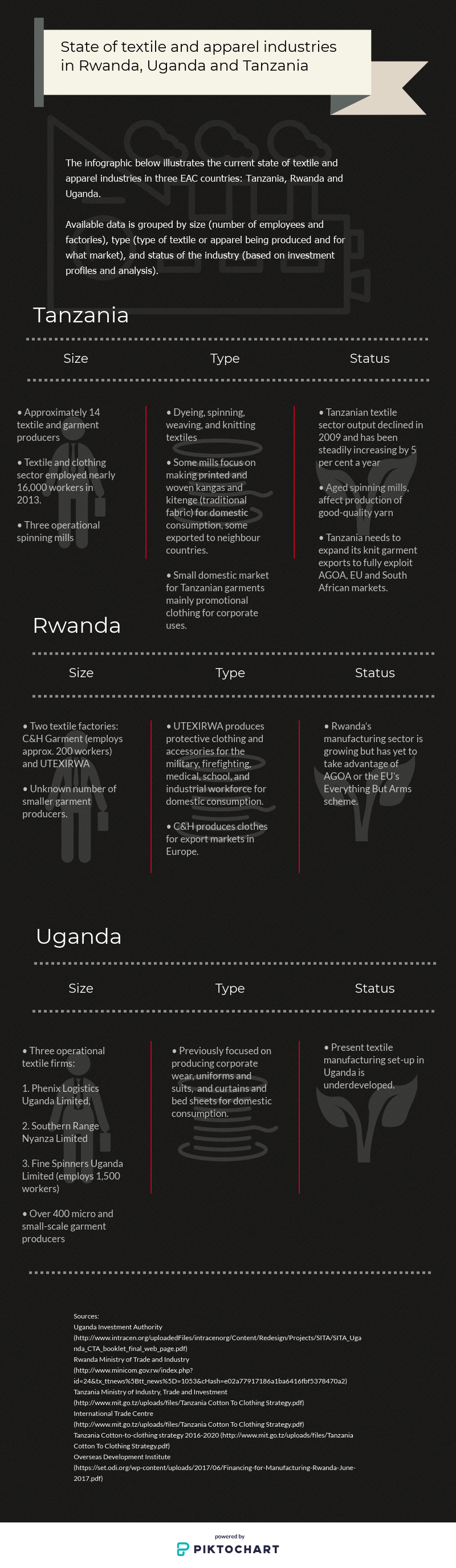

Currently Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda have small-scale textile and apparel manufacturing industries that produce for both domestic and international markets. The infographic below shows the available information on the different types of items each country produces, the approximate number of textile and apparel firms, and how many workers they employ and current ability to meet domestic and international market demand.

Impact of second-hand clothing

Garth Frazer, a University of Toronto economics professor specializing in the industrial development of Africa, established that there is a causal relationship between the rise in imports of second-hand clothing and the decline of the textile manufacturing and apparel industries across sub-Saharan Africa including Tanzania and Kenya. Due to the lack of data sets for Rwanda and Uganda they were excluded from the analysis.

Using data from United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and UN ComTrade he established a link between used clothing imports and declining garment production between 1981 to 2000. Frazer found that used clothing imports had a significant negative impact on the apparel production sectors in sub-Saharan African countries (including Tanzania and Kenya) and were responsible for 39 per cent of the decline in apparel production annually and roughly half of the decline in apparel employment.

It’s likely the impact is much greater as the UNIDO and UN ComTrade data only account for legally declared imports and fail to capture all used clothing entering the countries as smuggled goods. However, while second-hand clothing has played a role, some experts point to a combination of factors including lack of government support to the garment sector, poor infrastructure and limited access to a semi-skilled workforce to explain the failure of domestic textile industries in the EAC.

The governments of Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda and Kenya have long blamed second-hand clothing imports for putting domestically produced apparel at a competitive disadvantage. The issue is two-fold: imported second-hand clothes undercut locally produced clothes and second-hand clothing imports have become vehicles for illicit trade.

Second-hand clothing is undercutting locally produced textiles due to the low cost at which they are sold, according to a report from the International Trade Centre on Tanzania’s 2016-2020 Cotton-to-Clothing strategy. The report found there is little demand for domestically manufactured clothes.

Second-hand clothes are acquired for free by way of donations and therefore the price at which they are sold does not include the cost of production, only transportation and sorting. This keeps the price very low and pressures local textile manufacturers to reduce their prices to compete.

Second-hand clothing has been proven to adversely affect African countries due to the low cost at which they are sold. A WTO case study examining the effect of second-hand clothing on Malawi found that second-hand clothing caused significant damage to the textile manufacturing industry.

KAM: ‘biggest threat to Kenyan textiles and apparel sector is illicit trade’

The biggest concern the Kenyan Association of Manufacturers (KAM) has is the threat of illicit trade to Kenya’s textiles and apparel sector. This is when new clothing is being imported under the guise of second-hand clothing and avoiding duties, taxes and other import fees.

“We are seeing more illicit products filter into the second-hand clothes trade, coming from the Middle East and East Asian countries,” KAM said in an email.

“When we have new goods being mis-declared, undervalued and evading taxes, they sell at lower prices, providing unfair competition to locally manufactured products.”

Paul Ryberg, president and a director of the African Coalition for Trade, has extensive experience with AGOA and is a legal representative for the KAM. He says the clothes that are being declared as used clothes at borders are in fact new.

“To qualify as used clothes, used clothes have to actually have been worn and show obvious signs of wear,” Ryberg said.

Instead, what is being exported as used clothes are “seconds that have never been worn, or inventory overstocks which have never been worn, and those shouldn’t qualify as used clothes.”

New underwear with store tags still attached is on sale alongside used clothing in Tanzania. (Megan McPhaden)

What options are available for EAC to combat flood of used clothes?

Due to the low cost at which imported second-hand clothes are sold, Ryberg thinks EAC countries have a strong case to impose anti-dumping duties, if they chose to go that route.

“Under anti-dumping law, when you are trying to determine the value of a product, you have two choices: one is the cost at which it is sold, but if you don’t have sales to compare, the other is what it would cost to produce,” Ryberg pointed out.

Since you don’t produce used clothes, “you could make a quite credible argument that used clothes are being dumped in Kenya, Tanzania and other EAC countries.”

For the anti-dumping duty to be implemented, the country of import is required to prove a relationship between the imports that have been dumped and the injury to domestic industry. Textiles are a common sector for anti-dumping duties. From January 1995 to December 2011, textiles accounted for the fifth largest number of anti-dumping duties behind base metals; chemical products; plastics, resins and rubbers; and machinery and electrical equipment, according to WTO data on global anti-dumping duties by sector.

Anti-dumping duties are implemented by countries worldwide to deal with the issue of goods that are being sold below fair market value and as a result causing injury to local industries in the country of import. To deal with the issue of second-hand clothes, Malawi has explored using anti-dumping duties to safeguard their local textile manufacturing industry. Currently no EAC countries have introduced anti-dumping duties on second-hand clothing, partly because of what Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda stand to lose if the U.S. decides to withdraw their AGOA benefits.