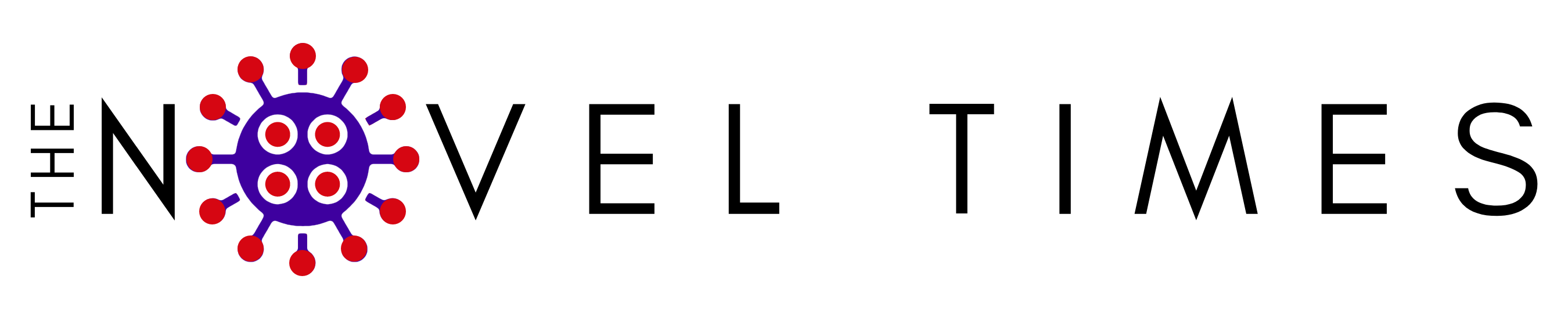

A cardboard sign held up by a climate striker in Montreal on Sept. 27, 2019. (Photo by Morgane Wauquier)

A year after the global climate strikes, youth climate activism persists in Quebec

MONTREAL – Ashley Torres and other student activists in Montreal had a whole week of strikes planned shortly before the pandemic started to take hold in March. But when COVID-19 sent everyone into a lockdown, these young activists had to put their protests on hold. Everything they had been working towards came to an abrupt halt.

“It was hard because we were in the middle of a momentum. It was heartbreaking. Some students had taken a break from their semester to invest in the week of strike,” says Torres, a climate activist. She is a member of the Coalition étudiante pour un virage environnemental et social, or CEVES, a Quebec student coalition fighting for climate justice.

In September last year, the climate strikes in Montreal saw hundreds of thousands of young people in the streets. This year, COVID-19 has shifted the public’s attention to other issues.

Much of the focus has been on prioritizing public health and rebuilding the economy. The climate crisis has seemingly been put on the backburner. Young climate activists in Quebec had to find new ways to adapt and maintain momentum.

One of their biggest challenges has been protesting.

Ashley Torres, climate justice activist and member of CEVES in Montreal, talks about what the COVID-19 pandemic is teaching us about the climate crisis. (Video produced by Morgane Wauquier)

Louis Couillard, Montreal student climate organizer and mobilization campaigner for Greenpeace Canada, said protests have become nearly impossible because of all the public health guidelines in place.

Couillard says that even simple protest tactics have become complicated. “Painting a huge banner in these times of COVID-19 is just so hard,” he says, referring to ‘banner-dropping’, a tactic where a large protest banner is displayed publicly, such as on bridges.

Before the pandemic, the activists would come together to paint a large banner. Now, they come one-by-one to paint. Couillard says sometimes, they each work on a small part of the banner and sew all the pieces together at the end.

Torres says losing in-person protests means losing some activists. Those who were more passive in their mobilization or were unable to give several hours to the cause would usually protest, she says. That’s not possible anymore.

A lot of the activism has moved online, but she says it’s not the same. “We’re still trying to figure out how to create that sort of excitement that protests created. Online, you don’t get the same impact.”

Climate strikers gathered on Park Ave. in Montreal on Sept. 27, 2019. (Photo by Morgane Wauquier)

“It’s not always as appealing and you don’t always get the sense that you’re making a difference,” Couillard said.

He adds that this is especially true for student activists. “People spend their whole life on Zoom, so they don’t want to do more volunteer time on Zoom after class.”

In September last year, the climate strikes in Montreal saw hundreds of thousands of young people in the streets. This year, COVID-19 has shifted the public’s attention to other issues.

For Aya Arba, 14, a member of the youth environmental education organization Environnement Jeunesse, it’s a loss. “It was an effective way to show what we believe in.”

Mobilizing online also has its technical difficulties. Exchanging equipment with peers is harder, says Arba.

Microphones have to be kept off when you’re not speaking during meetings, so people talk less with each other, explains Arba.

Sacha Wright is the research and impact coordinator at Force of Nature, a not-for-profit organization that helps young people talk through their environment-related anxiety online. She says that although doing things online gives people the opportunity to reach those who couldn’t be reached before, it doesn’t offer the same immediate support system that you would find in person.

“For some young people, it’s really added to a feeling of isolation for them where they feel like they’re very alone in the problem,” says Wright.

In Quebec, youth activist groups are actively fighting against the proposed GNL Québec gas pipeline project as the pandemic continues to wreak havoc.

The project would help transport gas from Alberta to the Atlantic. It involves building 750 kilometres of new pipeline between eastern Ontario and Saguenay, Que., where a new gas liquefaction plant would also be built. Greenpeace says the project would increase greenhouse gas emissions, threaten beluga whales in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and pass through Indigenous communities.

Environmental activists, outside Hotel Le Montagnier where consultations on the project were being held in Chicoutimi, Que., on Sept. 21, 2020, show what tourism would look like if the GNL Québec gas pipeline project proposal was accepted. (Photo by Thierry Lambert)

At Environnement Jeunesse, Arba and other activists drafted a report to stand against the project. For Couillard, getting the project rejected has been at the centre of his activism these past few years.

CEVES is a part of a national campaign against the project, too. But Torres admits that “bringing awareness in general for this project has been a bit more challenging this year, because we don’t have access to doing a mass protest and creating an uproar.”

The government is expected to announce their decision on the proposal in January, but Torres says it’s not looking good. She says she’s concerned it will be accepted because everybody is focused on COVID-19, so the public and the media aren’t paying attention to the issue.

The lack of media attention, especially, has been frustrating for these activists. “The crisis is still there even though the media are talking about something else,” says Couillard.

He says that the pandemic hasn’t been easy for organizations that rely on personal donations, but it’s been harder on grassroots groups. They survive because there are, “people that are willing to still put a bit of volunteer hours in despite the crisis that’s going on.”

Demonstrators wearing masks ride their bikes to protest against Coastal GasLink, a pipeline project, in downtown Montreal in June, 2020. (Photo by Félix Legault-Dignard)

Despite the challenges, this year hasn’t felt like a total loss for some young people. Torres recalls a bike protest CEVES organized in Montreal this summer in solidarity with Wet’suwet’en chiefs against another gas pipeline project, Coastal GasLink. The protest allowed CEVES to create ties with Indigenous Peoples, whom they now plan to work closely with.

For many youth climate activists, the pandemic is proof of how fast governments can act in times of urgency. “The government can listen to experts for the pandemic, so why not listen to experts for the climate crisis?” says Couillard.

But Couillard adds he’s afraid of the post-pandemic fight for the climate. “Whenever we’re rebuilding from a crisis, we have a tendency to go back to old habits which are bad.”

Torres acknowledges that it’s difficult to see climate as a concern when people face so many other problems, but she says she chooses to stay optimistic.

“It can be very depressing if you don’t stay and you’re not hopeful,” she says. “I think the 500,000 people that marched with us in the streets [last year] – they’re still here. We just need to energize and mobilize that base again, but people are still caring. People are still worried about the environment.”

The interview with Aya Arba for this article was conducted in French and translated to English.