Cavin Hayer, 25, is both excited and apprehensive about the metaverse. (Photo by Rajpreet Sahota)

For Cavin Hayer, the metaverse is the future and young people must prepare.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if the metaverse is the next step of what social media has already done to our society,” Hayer said, “whether that’s good or bad. I’ve got mixed reviews.”

Hayer, 25, a finance manager who works for Bell Media in Toronto, thinks the metaverse is a virtual movement as powerful as globalization.

One of the principal architects of this digital world, Mark Zuckerberg, recently capitalized on the idea of the metaverse by changing Facebook’s name to Meta Platforms.

What all this means for how people will interact with one another in the future is murky. There are significant grey areas as far as regulations to address issues with sexual harassment and other ethical considerations in virtual reality spaces. But as the world inches out of the COVID-19 pandemic, major companies are flocking to invest in the next age of the internet.

And that has some advocates embracing this brave new world.

An entirely virtual space to interact

The term “metaverse” is credited to author Neal Stephenson in his 1992 science fiction novel, Snow Crash where he described lifelike avatars who met and interacted in 3D environments.

For Zuckerberg, this means creating an entirely virtual space to exist and interact. Big tech companies have been building the metaverse infrastructure for the past decade. New models of smartphones are all augmented reality capable and virtual reality is finding ways to seamlessly enter the everyday world.

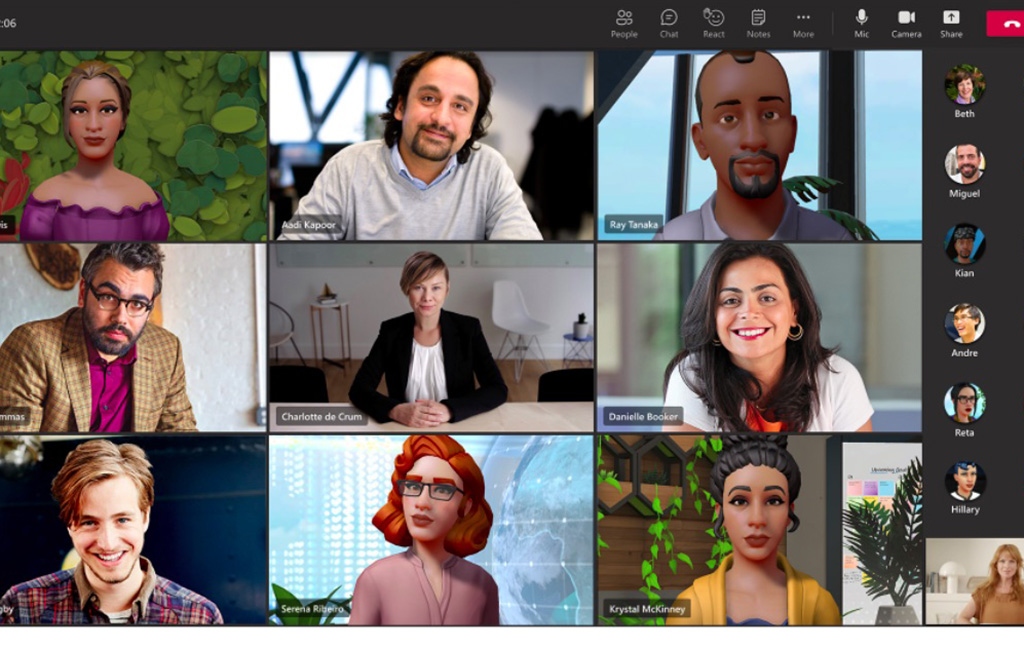

Meanwhile, Microsoft has highlighted how it plans to allow employees to meet in virtual spaces with their avatars using the Teams infrastructure they are already familiar with.

Won Sook Lee, an engineering professor at the University of Ottawa, specializes in the human-computer interaction.

“Better human-computer interaction has the possibility to bring more equal opportunity to people,” Lee said. “We have to develop this technology to make it more comfortable.”

Lee said with any new technology, a small group adopts it quickly. A much larger group, sometimes referred to as the “moveable middle,” will pick up the tech only once the kinks have been worked out and they can seamlessly incorporate it in their life. Making this technology more comfortable can have the power to draw in Canadians who are hesitant about trying it.

When considering the COVID-19 pandemic’s rapid advancements in digitization, or virtualisation as Hayer put, Lee said the direction of the metaverse is one that has been chosen for us.

“We have to think, is this really the good direction for humankind?,” Lee asked.

When virtual lives become ‘more enjoyable’ than real lives

Hayer is excited about the business opportunities available in the metaverse, listing off real estate, casinos and shopping centres as enticing avenues for investment.

Hayer also emphasized the opportunity for job creation through the metaverse.

“When I enter the metaverse casino, there is a virtual black-jack dealer who is maybe working somewhere on the other side of the world,” Hayer said.

“I am gambling, and they are getting paid to do that work.” Hayer said, adding he is excited by the prospect of introducing a human element to what was once a solitary experience on 2-D gambling platforms.

Hayer explained this monetization resides in the individuals using the platform and away from centralized websites like Facebook or Instagram. For example, in the metaverse you can create marketing spaces that do not exist in the real world. The potential for profit is skyrocketing, with real-estate currently selling for millions.

Hayer explains how there is finite real-estate to be purchased in the metaverse.

“The opportunities are endless, particularly in entertainment and retail,” Hayer said. He spoke to the new level of consumerism that is at its dawn as people will begin to purchase things for their Metaverse avatar.

“We all like stuff, and now we can begin to like stuff virtually,” Hayer said.

At the same time, Hayer expressed concern over where to draw the line in placing too much value on something that is not real.

“We are already at the point where we all have a social profile where we identify ourselves in some form of social world,” Hayer said.

“At the moment, we only have one screen, say an Instagram page. In the metaverse, we will be able to welcome our friends to our metaverse house to see how our friends live and dress.”

Jonah Brotman, 35, co-founder and CEO of Canada’s leading virtual reality (VR) services company House of VR, is proud to use his company’s reach to employ VR as a tool for empathy building in schools and communities.

Still, he is skeptical of the metaverse’s ethos. It’s being created by large companies for their own objectives, pushing young people to spend even more time on their screens than they already do.

“As Meta is growing, I worry that they are going to have in head-set advertisements at some point, and it would be terrible because you can’t look away,” Brotman said.

When he founded the company in his early 30s he did not know the success it would see.

House of VR now leads diversity and inclusion workshops using VR devices, produces VR empathy films and does in school programming for education purposes.

“The scary tipping point will be when people find their virtual lives more enjoyable than their real lives,” Brotman said. “For many people in this world, that will not be that difficult. That is scary and the implications for that are really major.”

Brotman echoed Hayer’s belief that it is more intriguing to be in the metaverse with your friends, than passively scrolling with your thumb on a cell-phone.

Hayer cautioned users may come to enjoy VR more than their normal life.

“If this reaches a point where social media is today, what will you value more, your identity in the metaverse, or your identity in our real universe?” he asked. “The way I see the metaverse is that it is unstoppable at this point.”

Capacity for harm

Thea Berringer, 27, opened Colony VR in Ottawa in 2015 along with her parents and brother. The family’s vision was to host a community space to share their excitement about VR and offer the opportunity for groups to try out immersive experiences.

Echoing Brotman, Berringer explained VR is an empathy machine which allows people to fully immerse themselves in the perspectives of others.

“However, I also think the reverse is true. When you are getting rid of barriers, there is real risk of desensitization.” Berringer said.

“The abstraction of digital and real in VR is much slimmer,” she explained. “You are still touching someone’s body for example, even if you are not physically there.”

Sexual harassment was prevalent in Colony VR’s unique social settings. The conversation on consent became a routine need for teen parties held at Colony VR as sexual harassment of participants’ avatars was a daily occurrence.

Berringer, who now studies in the interaction, design and development program at Toronto’s George Brown College, explained a majority of those working in designing the infrastructure of VR are often male-presenting and white. This can inform the cultural and racial expressions they offer for the avatars that exist in the metaverse. This can also influence how the virtual infrastructure is coded, making it inaccessible to users who may not fit the coder’s own profile.

On top of this, Berringer is concerned about the loss of community spaces that are not privately owned. Can you loiter and just go for a walk in the metaverse, or do you always have to be consuming and engaging with something?

Since the pandemic began, her family business had to close its physical doors and now leads virtual workshops on VR for Ottawa based businesses.

Knowing about the shortfalls in VR regulation and ethics, Berringer was motivated to become an architect in the field and limit its capacity for harm.

What does this mean for the future?

Brotman pointed to the importance of QR codes during COVID-19 as an example of how quickly the metaverse is becoming a norm.

“The goal is the blurring of digital and physical realities. It is going to happen,” Brotman said. “Right now technology is moving so fast. However far you think it is away, it will probably happen faster.”

Brotman wonders how his intrinsic desire to be outside and interact with other humans in person will mesh with the pull of the growing metaverse.

“If I’m totally honest, I am a little dystopian about it,” Brotman said. “I actually see more harm than good and that’s what concerns me.”

Despite some trepidation, Hayer is leaning in.

“People are starting to come around to the sense that it is here, especially because of COVID. This is the next step in terms of where technology takes us,” Hayer said.

There is a lot of cautiousness among his friends who are not already using it, while those who do are excited, he added.

“This tells me that the more people use it, it will become mainstream quicker because the excitement will spread like wildfire.”