The devil you know

Photo illustration by Hannah Rivkin.

As reports of vaping related illnesses mount, both pro and anti-vaping advocates are calling for change.

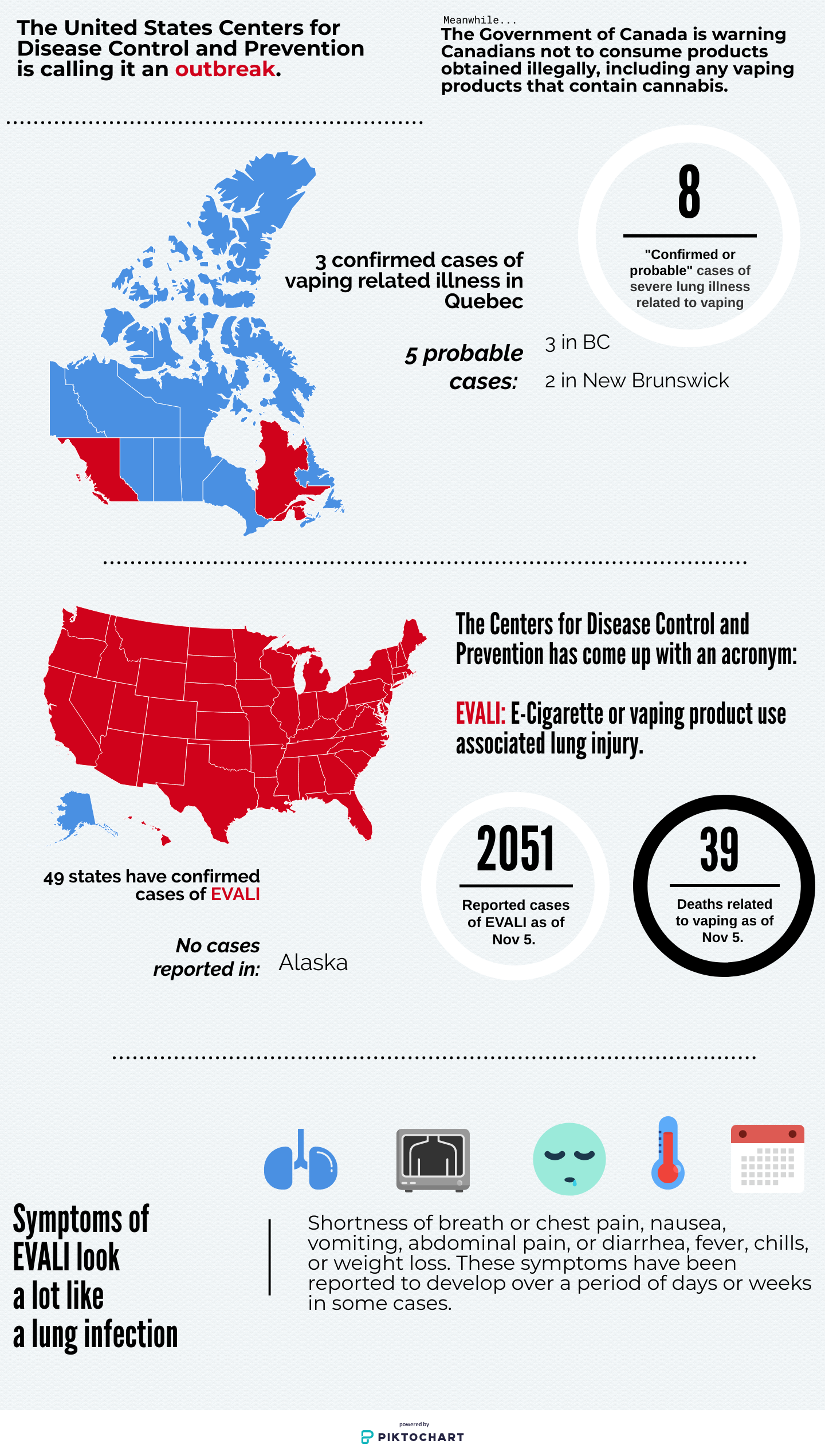

On Thursday, the eighth Canadian case of vaping-related illness was confirmed in the Outaouais region.

The Nov. 14 confirmation arrives on the heels of heated debates from public health experts on how the government should be responding to the rise in popularity of vaping.

Pro-vaping advocates argue these devices decrease rates of cigarette smoking, a known killer. Those on the anti-vaping side fear that charging full force into a cloud of vaporized chemicals could be hazardous.

“To purposely inhale something that is not known to be safe and is considered to be dangerous, even though the exact nature of the dangers aren’t known, is risky,” said Cynthia Callard, the executive director of Physicians for a Smoke Free Canada.

“For us to know the exact dangers on human beings means we have to kill people.”

Callard’s Ottawa-based think tank addresses tobacco issues. The vaping question, she said, is one of the first times she has seen the scientific community divided on tobacco issues.

“Pro” vaping arguments purport that it is a safer alternative to smoking, a tool known to be much less harmful than cigarettes in the short term.

On the flip side, Callard said there is a lack of long-term human health data on vaping and correlation to death or illness.

Questions around who has died or gotten sick, and how does that correlate with those who vaped over the long term, have yet to be answered.

Callard said there’s a silver lining to the recent high profile vaping related deaths and illnesses: people are finally paying attention.

Sources: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Government of Canada. Graphic Illustration by Hannah Rivkin.

The harm reduction free market debate

David Sweanor, an active advocate for a pro-vaping market, said that getting smokers to switch to vaping “would be one of the biggest breakthroughs in public health ever.”

He is an adjunct professor of law and the chair of the Centre for Health Law, Policy and Ethics at the University of Ottawa. He also sits on the international advisory board for the Boston University School of Public Health.

Fueled by massive popularity and profits, the vape is quickly becoming sleeker, cheaper and better able to deliver more nicotine. According to Sweanor, this is a good thing.

Competition accelerates product advancement. For Sweanor, this means safer and cheaper products for those who wish to make the switch.

While vape products may improve, questions remain on how even the most perfectly designed and regulated vape products would affect human health over long periods of time.

Research has a solution: experiment with animal and human tissue.

For Sweanor, doing this research is imperfect and causes undue fear.

For Callard, the results of animal and human tissue research prove worrisome.

In a 2018 study that used both mice and cells, for example, it was demonstrated that chronic exposure to e-cigarette vapour led to thickening and scarring in certain organs, as well as a significant increase in inflammation.

These kinds of studies are a start, but don’t always reflect what is being consumed in the market. Much of this research was initially funded by tobacco companies themselves. Different devices heat the vaped liquid to different temperatures, and introduce an array of chemicals into the body.

There are a thousand possibilities for a product that has already made its way into the mainstream.

Ban-ish?

In the meantime, people are asking if the federal government should be imposing heavy regulations on the vaping market, such as banning flavours that appeal to young people. Sweanor says no.

“People will turn to the black market, a less safe unregulated version of what is currently offered,” he said. “It is knockoff products from the blackmarkets that are causing many of the vaping related health issues.”

Since the 1980s, he has taken a very active role within public health issues, particularly dealing with smoking. Sweanor emphasized another disastrous effect of heavy “non-rational” regulations: people returning to cigarettes for their nicotine habits.

“There are 40,000 deaths a month in the United States from smoking cigarettes,” said Sweanor.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States estimate there are 480,000 cigarette-related deaths each year. In the last year, the centers have reported 39 deaths related to vaping.

Even in the context of recent deaths, then, vaping appears to be a safer option.

A 2015 study by the Royal College of Physicians found that according to “best estimates” e-cigarettes are around 95 per cent less harmful than smoking.

In that same study, researchers found that “nearly half the population, 44.8 per cent, don’t realize that e-cigarettes are much less harmful than smoking.”

Should consumers be thinking about trading in one high risk activity for another, less risky one, at least in the short term?

For Sweanor, the logical answer is yes, and let the free market do the work of engineering an ever-better, ever-safer product.

Moral panic, hype and stigma

Last winter, reports of schools removing doors on washrooms to prevent student vaping scandalized Ottawa residents.

This worries Sweanor. He said perceptions of vaping could prevent people from switching to a safer alternative.

On a wider scale, there has been a reactionary push in the U.S. to ban all flavours except tobacco and menthol. For Sweanor, this would be a dangerous move.

On Oct. 1, 72 specialists in nicotine science, policy, and practice wrote a letter to the World Health Organization.

In it, the authors call for a more positive approach to new technologies and innovations, with what comes down to an essential message: no combustion, no cancer.

This truth may be tenable for the vape enthusiasts, but only temporarily.

No combustion, no cancer – as far we know, at least for now.

Nepean man quits both

It’s been three years since Jonathan Markus, 26, quit smoking cigarettes, and three weeks since he quit his vape.

“I was using it all the time. All the time. Like it was an extension of my arm. If I didn’t have it on me, I would start getting anxiety,” said the government employee.

He initially began vaping in 2016 as a way to quit smoking cigarettes – something he had been doing since he was 13.

Markus started with the most basic version of the vape. It was klunky, slow to heat oil, produced less vapour and delivered little nicotine compared to today’s models. But he quickly upgraded.

“I bought a new vape – you know, bigger and better, bigger clouds and more flavour and everything. So really I could get more enjoyment out of the vape.”

Three years later, Markus quit vaping. It took him two tries, some strong words from his girlfriend, and recurring headlines about vaping illness.

Greenspace Gripes

Kanata residents aren’t sure the grass is greener when it comes to plans for local golf course

Waiting, Wishing, Wondering

Transit woes may be new to LRT riders, but Para Transpo users have lived with unreliable transit for years.

To Heck With Sugar and Spice

Carleton Ravens female basketball players are inspiring female athletes to combat sports stereotypes.