Shoal Lake 40, pictured here, has not had clean drinking water for years. (Photo provided by Council of Canadians, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

OTTAWA — Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on Friday would not commit to a new deadline for his promise to end all drinking water advisories in Indigenous communities.

At a press conference outside Rideau Cottage, Trudeau said the COVID-19 pandemic has delayed the government’s progress.

“There are situations in which COVID-19 has interfered with our ability to work hard to get these new installations in, but we are continuing to redouble our efforts because it is unacceptable that any Canadian across the country does not have access to safe clean drinking water,” he said in a response to a question from The Novel Times.

His remarks came after Indigenous Services Minister Marc Miller announced on Thursday the government would not fulfil its pledge to end advisories by March 2021.

Miller said in a press conference that COVID-19 delayed construction and impacted Ottawa’s ability to meet its deadline. He claimed responsibility for missing the deadline and defended Trudeau’s decision to impose it.

“As a Canadian, the prime minister did what would be expected of any leadership and said we want to get this done,” said Miller. “When you talk to communities about that deadline they’ve said — and rightly so — this is your deadline, and you need to walk with us and invest in our priorities.”

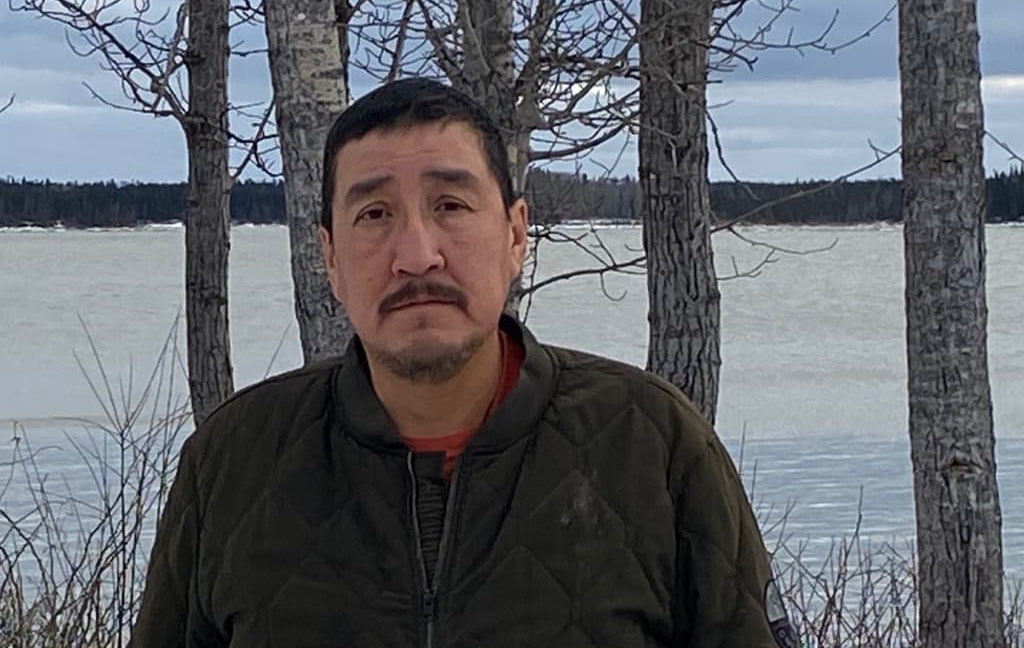

Nathan Neckoway, councillor for Tataskweyak Cree Nation, says his community on the Nelson River in Manitoba has been without safe drinking water since 2017.

“We’ve proven that the Nelson River is not safe to drink. We cannot drink the water, we cannot access the water and our kids can’t swim in the water. We cannot eat any fish out of the water due to fish being sick and dying,” he said.

Tataskweyak filed a feasibility study in 2018 to determine whether it could get its drinking water from another river system. It is still waiting for a response.

“If on the federal level they were serious about getting whoever off the boil water advisory, I’m pretty sure we would have gotten a response,” said Neckoway. “There’s always a deadline that they announce, but to me, deadlines for committing and doing this — they should be more approachable and communicative.”

Trudeau won a majority mandate in 2015 on a campaign that included a promise to end boil water advisories on reserves.

There are currently 59 long-term drinking water advisories in effect in 41 communities. The government’s progress towards lifting these advisories varies between communities, but in most cases construction is underway. The government has lifted 97 boil water advisories since November 2015.

“The fact that in too many Indigenous communities across the country, degraded infrastructure and lack of opportunities have led to decades, in some cases, of boil water advisories, has long been unacceptable,” Trudeau said.

Neckoway stands on the banks of the Nelson River. (Photo provided by Nathan Neckoway)

The government pledged an additional $1.5 billion investment towards lifting advisories in the fall economic statement released Monday. This additional funding will supplement the $1.65 billion it has already spent to address the issue since 2016.

Miller said there will be roughly 12 communities that won’t be able to lift their advisory by the abandoned deadline.

“This is a recommitment to them,” he said, referring to investments promised in Monday’s fiscal update.

In Tataskweyak, Neckoway is looking for signs of that commitment.

“I know their department is so occupied, busy with the COVID that is happening in the country,” said Neckoway. “But all in all, we’re still again here in our First Nation waiting for a response for this feasibility study.”

CORRECTION: At 10:20 p.m. on Dec 4, this story was corrected to indicate that Tataskweyak Cree Nation has been without safe drinking water since 2017.