The lottery

One morning in June, 22-year-old Dorjee Dolma woke to the sounds of birds and insects at 4:15 a.m. as the sun rose over the lush green land that surrounded her home. She remained still for a few moments as light poured over the Tibetan refugee settlement, tucked away in a remote corner of northeast India. It would be another 45 minutes before Delhi lit up under the sun and the buzz of traffic would jam the streets. At the settlement where cows, the occasional scooter, and smiling people strolled along the dirt road, life had a different pace.

Dolma pulled herself up off the queen-sized mattress on the floor. Her mother was already awake and in the kitchen boiling water for butter tea, a traditional Tibetan drink made with tea leaves, butter, milk, and salt. Dolma’s eight-year-old sister remained motionless on the bed where they’d spent the night together under the protection of mosquito netting and the subtle breeze of the ceiling fan.

Each day repeats itself in the Miao settlement. Dolma’s family starts the morning off with house work. They sweep, fill jugs with hot water for tea, pray at their Buddhist altar, walk to the monastery around the corner, and make several clockwise rounds of the building turning wooden prayer wheels as they go before returning home. From 5:30-6 a.m. they collect water from their taps, if available, which is usually about three times a week. The family stores water in industrial sized jugs for cooking, for dishes, for washing clothes and their bodies, and for the filtration system to make the contaminated water drinkable.

On this summer day, Dolma and her mother were busy cooking breakfast in the kitchen. One of them pounded the dough and rolled it out into chapattis, or flatbread. The frying pan sizzled as the other tossed in onions, tomatoes and okra mixing it with a little spice and a lot of oil. They also fried an egg for each family member and prepared a warm milky Horlicks drink mix as a nutritional supplement for the younger children.

From a distance, Dolma and her mother were like twins. They both had a short stature, their bodies bore similar feminine curves, and they had shiny black hair that was tied up away from their face. Their eyes were the most striking; dark rimmed almond eyes that would narrow as their cheekbones lifted whenever they offered a smile or an easy laugh.

In the living room, the only brother, Tenzin Yeshi, was already in his uniform and packing his bag for school while the youngest sister, Tenzin Dolkar, still wearing pink tights and a teal T-shirt from the day before, groaned whenever anyone tried to pull her out of bed. Dolma and her mother brought in the food and the plates, and their father joined them as everyone sat together on the floor for breakfast.

After filling their bellies, Yeshi met up with his friends and together they walked along the dirt road to the Central School for Tibetans, while little Dolkar went with her father on his scooter. Before class began, Yeshi, as head boy, led a hall full of students in singing Tibetan prayers. When the students sat down for class, their teachers told them that the school day would be cut short because the water supply wasn’t working and the cook couldn’t provide lunch for the students. This was a common issue in the remote refugee settlement, which lacks the infrastructure and resources to maintain a consistent supply of water and electricity to the people who live there. In the afternoon, Yeshi and Dolkar walked back home and sat around waiting for the electricity to come on so they could watch cartoons or Bollywood dance reality shows on their small TV.

At home their big sister, Dolma, hung out with them. For many years, she stayed outside the settlement, away from the family, to continue her education and then to search for a job. Once she completed grade eight at the school in Miao, she boarded at a Tibetan high school in another state, which took several days to reach by train. After high school, she went to college to study tourism, but a year later she dropped out when she caught tuberculosis from a friend. She recovered in south India at a treatment centre and eventually moved to Delhi to complete a hair design course. After starting her first job at a salon in the dusty city she heard the news – her turn had come, she would finally be able to cash in her winning lottery ticket, she was moving to Canada.

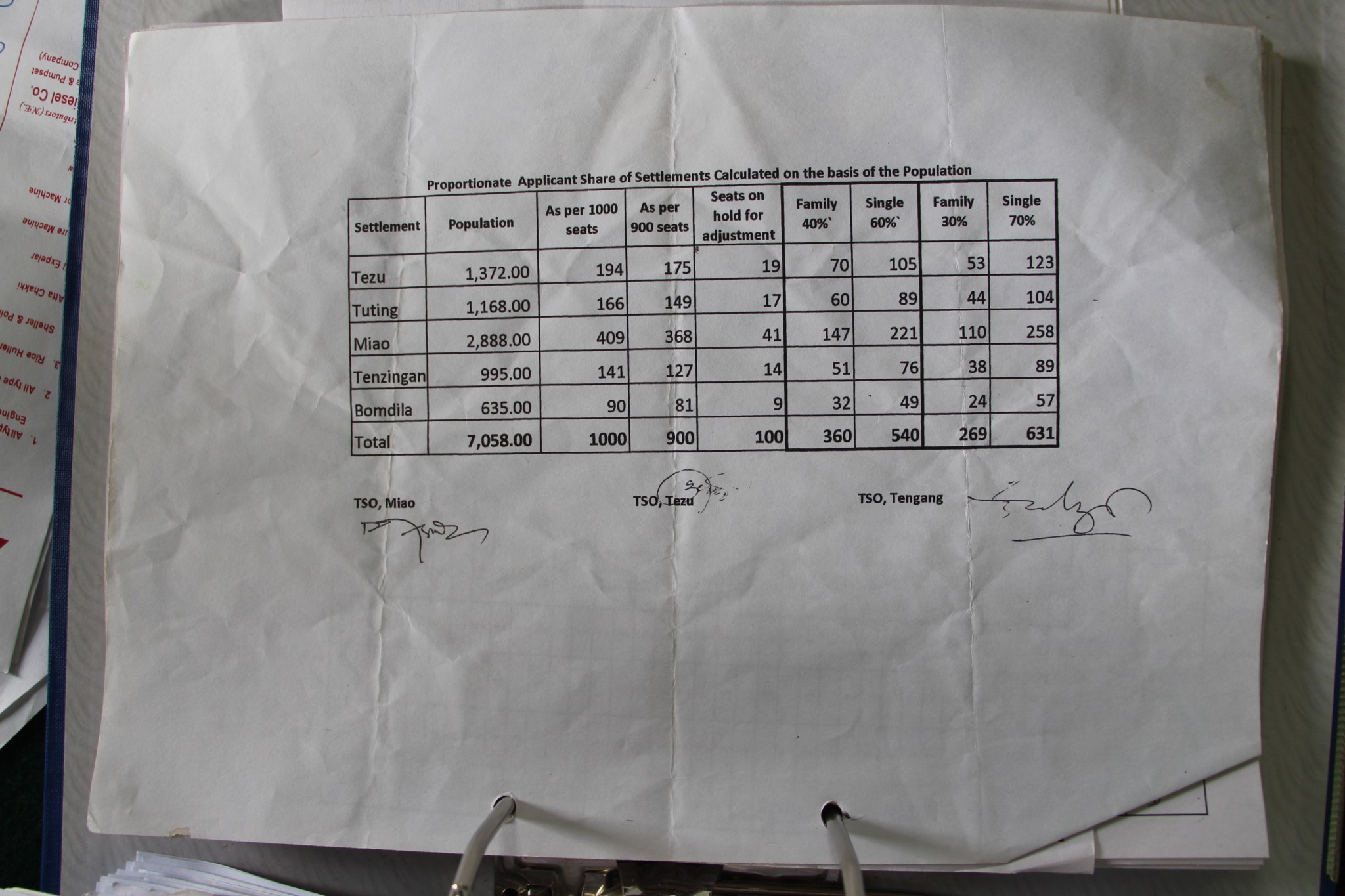

In 2012, the local Tibetan government-in-exile told the people of Miao that the Canadian government was accepting 1,000 displaced Tibetans from Arunachal Pradesh, the state where their settlement is located. The special resettlement program would let them rebuild their lives in a developed country. But there were about 7,000 people living in Arunachal Pradesh at the time so the government-in-exile organized a lottery. In Miao, only one person from each household could put their name on a ticket. They were allowed to apply as a family or as a single person, but more winning tickets would be selected from among the singles and Dolma was encouraged by her family to take the better odds. Of the 400 winning lottery tickets in Miao, Dolma got one of them.

Winning the lottery to come to Canada is a dream for many refugees. For some, the reality is not what they imagined, and for others, without any orientation, they have no idea what to imagine. Canada has a humanitarian tradition of resettling people in need of a new home. But over the years, the government has been offloading the upkeep of that tradition onto the backs of private sponsors such as community, charity, and church groups.

This is the story of 1,000 Tibetan refugees coming to Canada through a resettlement program in which private sponsors are working together to help these people start a new life. Without any government support, the Tibetan resettlement volunteers do their best with limited resources. There’s no orientation, no language or job training. The newcomers aren’t mentally prepared for life in Canada, and once they arrive they continue to be disconnected because they have to find work as soon as possible in order to support themselves.

This is the story of the Tibetans, but it is also the story of other groups who come to Canada through a resettlement project. The government announced in January 2015 that it’s opening its doors to 10,000 Syrians refugees. But the government expects charity and church organizations to look after 60 per cent of these refugees who are supposed to come over within the next three years. The Tibetan resettlement is over a five-year period, with the first two years dedicated to designing a plan for the project. Let’s explore how the resettlement project plays out for some of the Tibetans to understand how it takes a tremendously devoted and unified community effort to make a program like this work.

NEXT PART

Credits

Story and visuals by SHANNON LOUGH

Carleton University 2015