The plight of the Tibetan refugees

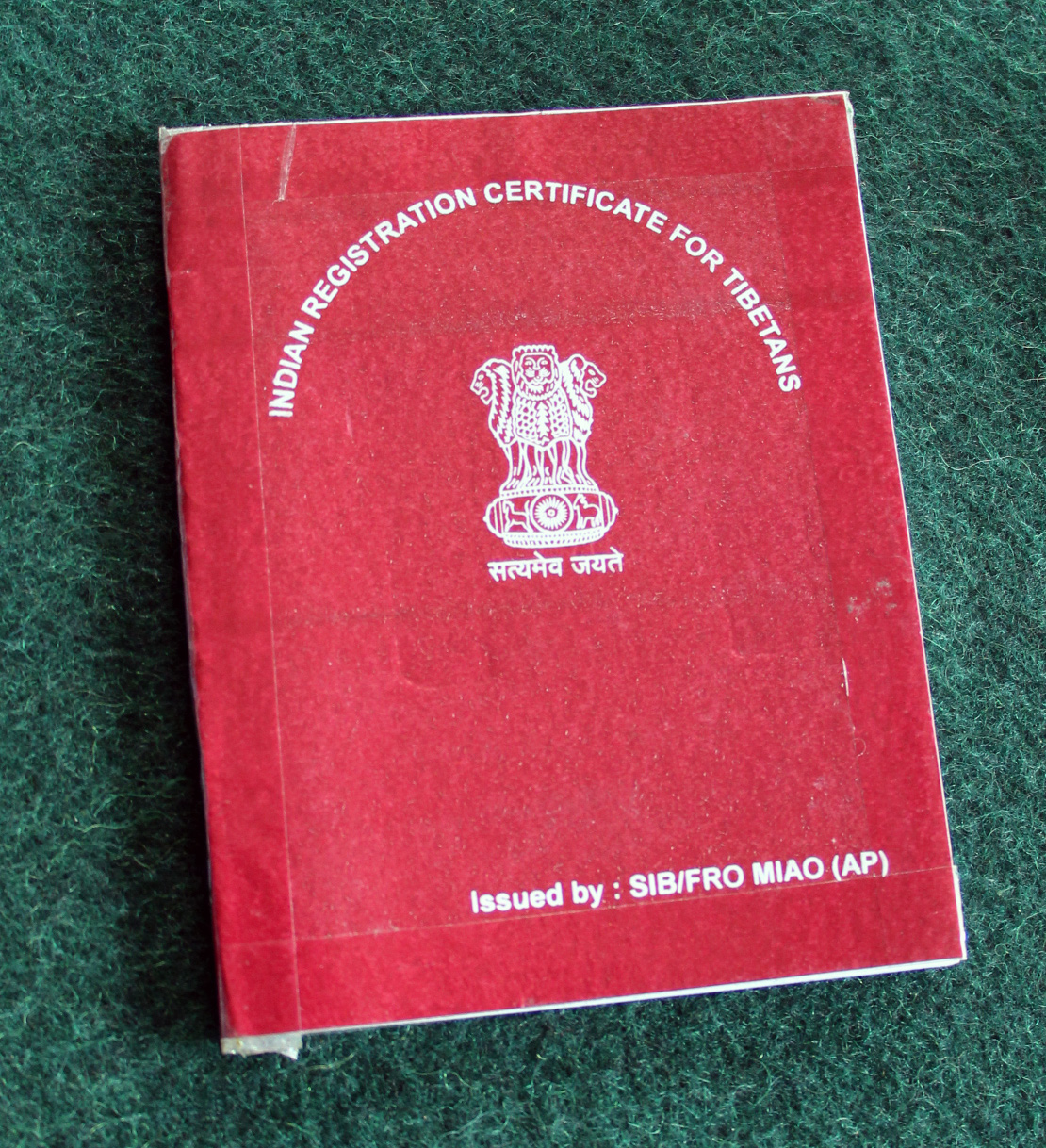

For Dolma’s entire life the Indian government had considered her a refugee, despite being born in India. She has an Indian Registration Certificate that gives her residence status, allowing her to stay legally as a refugee. The problem is that with her status she can’t get Indian citizenship, so she will always be a refugee in India, just not to the rest of the world. The Indian government never signed the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention that defines who qualifies as a refugee. To the rest of the 144 countries in the world who signed the convention, including Canada, she can’t be considered a UN refugee because of her situation in India.

Canada, for its part, has yet another definition of refugee, one that is more flexible than the UN convention. In 1976, the Canadian government introduced a policy that includes both the UN definition of a refugee and a special class that allows the government to accept people as immigrants based on humanitarian reasons. Fortunately for Dolma, in Canada she is able to qualify as an immigrant under a special policy created to help displaced Tibetans in her situation.

The Tibetan exodus began in 1959, the same year that Dolma’s parents and grandparents escaped. Her parents and relatives had lived in the isolated southeastern Tibetan region of Pemako, like most of the people who ended up in Miao. For years the Chinese government tried to occupy Tibet, and by 1958 Chinese soldiers began attacking Buddhist monasteries and towns, killing the monks and people who lived there.

The elders in Miao recounted their experience to me from that time. They said that from Pemako, it took a month to walk from Lhasa to their village, and reports of the invasion were slow to reach their community. Then they saw the invasion first hand when some Chinese soldiers reached their settlement, which was why some decided it was time to leave. Across Tibet thousands of others chose to leave in 1959 after the country’s beloved spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama, had fled to safety in India and the Chinese dissolved the government and placed the region under communist control. Dolma’s relatives joined the exodus and they trekked over the Himalayas to cross the border into India at Arunachal Pradesh. Since 1959, approximately 120,000 displaced Tibetans have found refuge in India, Nepal and around the world.

The Indian government accepted Dolma’s parents and relatives, along with the other Tibetan refugees, and gave them land to build settlements and separate schools to protect their traditions. It allowed the formation of a government-in-exile, with the Dalai Lama as its leader, in Dharamsala, a town in the hills of northern India. India gave the Tibetans refugee status, but not citizenship, and so they would always be a displaced community until they could one day return to Tibet.

The Dalai Lama continues to have a ubiquitous psychological and spiritual influence over the Tibetan people in exile. He led the government-in-exile until 2011 when he retired from his political role. Exiled Tibetans from around the world voted in a democratic election and appointed Harvard law scholar, Lobsang Sangay, as their prime minister. But the Dalai Lama is still their spiritual leader, and in the Tibetan settlements his presence is everywhere. His image is found in the monasteries, hanging above Buddhist altars in homes, and even as a charm worn on a necklace. The Dalai Lama’s guidance of non-violence, compassion and looking after one another is what keeps the exiled Tibetan communities thriving in an attempt to preserve the culture from their lost homeland.

For almost a decade after escaping Tibet, Dolma’s parents and grandparents tried to survive in Changlang, near the India’s northeastern border with Myanmar, where hills and uneven land made farming difficult. In the seventies, the government of India and the Tibetan government-in-exile saw their struggle and launched a habitation program in Miao. Dolma’s parents and grandparents packed up their belongings with the others and moved to Miao where they were confronted with flat land covered by a dense jungle.

Dolma is young, like many of the others immigrating to Canada, and she has only heard the stories from her parents and relatives of what it was like back then. The settlement officer in Miao, Dawa Tsultrim said he remembered how “the area was full of thick forest and after you enter into the forest you couldn’t see the sky easily. But now, it’s all gone due to infrastructure development and the forest disappears every year.”

NEXT PART

Credits

Story and visuals by SHANNON LOUGH

Carleton University 2015