The Dalai Lama’s request

Resettling a group of refugees is not an easy task, and while Dolma was in India she had no concept of the enormous process it took to find her a permanent home. For many Canadians it’s unfathomable, but it’s important to grasp the complications of just one newcomer’s story.

In 2010, the Canadian government created a temporary public policy to accept 1,000 displaced Tibetans in Arunachal Pradesh as a burden sharing agreement with India. But the burden was shared with private sponsors, the Canadian-Tibetan community, and not with the government of Canada. This policy is an example of how the government has offloaded the responsibility of resettling refugees, or displaced people, onto private sponsors. This results in an immense amount of pressure placed on both the resettlement volunteers and the refugees. In the case of the Tibetans, they were unprepared for life in Canada and once they reached their new home they were given only three months to be on their own and economically self sufficient before the next group from India arrived.

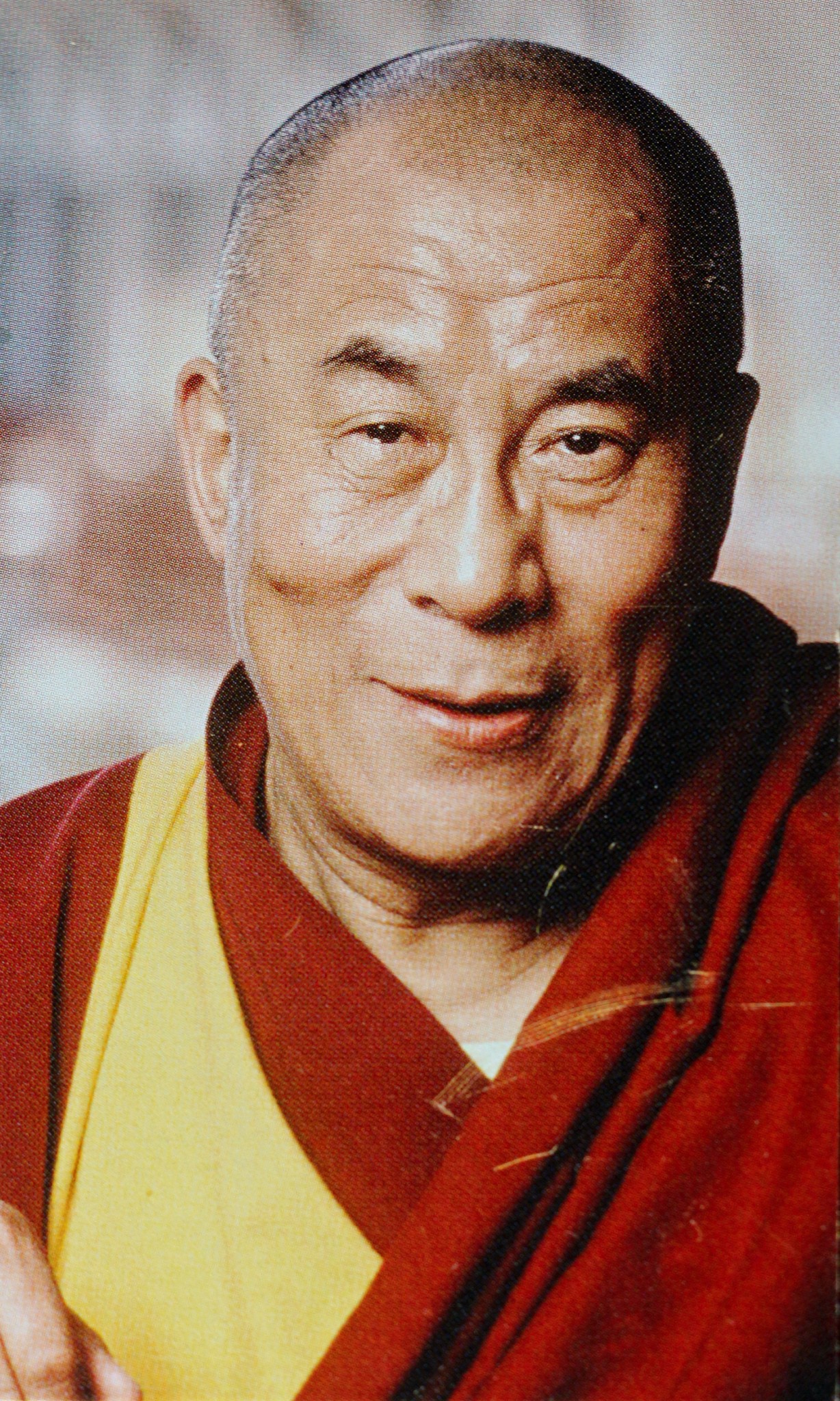

Dolma was still in high school in October 2007 when the Dalai Lama went to Ottawa and asked the Canadian prime minister to accept 1,000 Tibetan people from the Indian state, Arunachal Pradesh, where she and her family were living. The Dalai Lama originally made the request to the government a year earlier when he came to Vancouver to receive honorary Canadian citizenship. The purely symbolic honour for the Nobel Peace Prize winner didn’t persuade the government to accept his appeal until many years later. This was possibly due to concerns that China, one of Canada’s biggest economic trading partners, would break ties with the government if it helped Tibetan refugees. The Chinese had already responded to the Dalai Lama’s visit in 2007 by cancelling a number of high-level meetings between the two countries, according to a report retrieved through an access to information request.

At the time, the government was attempting a balancing act with China. “Although the government was supportive of the Tibetans and critical of China’s human rights record, it was at the same time trying to build stronger relations with Beijing, particularly on trade,” says Howard Duncan, the executive head of Metropolis, a think-tank that focuses on immigration policy. “This meant that the discussions or negotiations on admitting Tibetan refugees were complex and lengthy.”

In 2010, a new Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, Jason Kenney, who is also a member of the Parliamentary Friends of Tibet, declared that the government was willing to accept 1,000 Tibetans living in Arunachal Pradesh through a one-off resettlement program designed specifically for this group. There were two catches: there would be a deadline – to bring everyone over by May 2016 – and the government wouldn’t spend a dime.

“Technically the displaced Tibetans don’t meet the (UN) convention definition of a refugee. We already have a lot on our plate in terms of sponsorship of refugees,” said Conservative MP Bernard Trottier, who chairs the Parliamentary Friends of Tibet. The government was already spending millions in refugee assistance and didn’t feel they should spend more to accommodate the Tibetans, even though there was government research that showed Tibetans could be settled at a relatively low cost, according to Brian Given, a Carleton University anthropology professor who studied a group of 228 Tibetans who came to Canada in 1971 under a government funded resettlement program.

Trottier said that to avoid diverting funds to support UN convention refugees from war torn areas, the government reached an agreement with the Tibetan community in Canada to create a resettlement model that would place all the financial responsibility on the sponsors. The community also committed to prevent the newcomers from receiving any social assistance.

The weight of the responsibility fell on the shoulders of private sponsors: Tibetans already established in Canada and compassionate civilians who had an affinity to Tibetan culture. Many of the non-Tibetans who participated in the resettlement were Canadians who practiced Buddhism, or who’d met kind-hearted Tibetans and empathized with their plight.

Norman Steinberg, the founder of the Tibetan Resettlement Project Ottawa, said the project was born out of need to save a threatened culture.

“It’s a culture that is deeply rooted in the wisdom tradition, that’s based on non-violence and that’s unique in the world today, and if the light of that culture goes out then the world is going to be a darker place,” Steinberg said.

Tashi WangdiWe hope there will be a vibrant Tibetan community here while preserving our own culture, traditions, and our identity, but at the same time to be an active part of the society here.

NEXT PART

Credits

Story and visuals by SHANNON LOUGH

Carleton University 2015