Finding a new life in Ottawa

The journey to Canada stretched out for 16 days. Namgyal and a group of others took the four hour bus ride to Tinsukia to catch the train to Delhi. Two days later they arrived to the hustle and incessant honking of auto rickshaws and taxis in the city. They stayed in Majnu-ka-tilla, the Tibetan district of Delhi, for a few days and spent their remaining time in India meeting up with friends, relatives and shopping for things they thought they needed, like winter jackets.

Just before Namgyal left, he met an official from the Tibetan government-in-exile who told his group that Tibetan people are known for compassion and they should continue to be good people in Canada, but most importantly – don’t forget your culture.

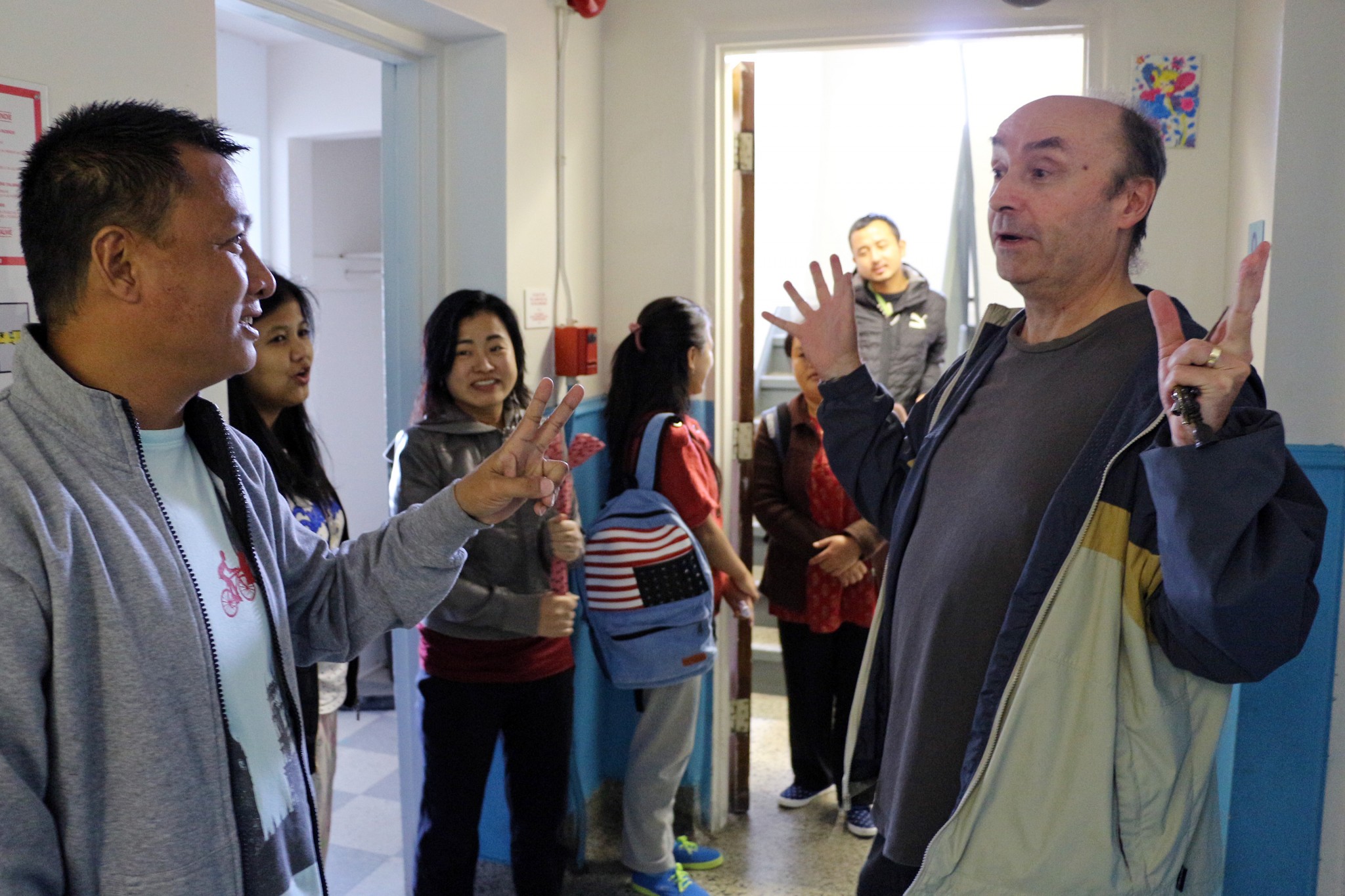

The group destined for Ottawa flew out together. As the plane took flight over Delhi and into the clouds, Namgyal clutched onto his prayer beads and continuously chanted “om mani padme hum” to calm himself down. His friend who sat beside him, Tenzin Wangdak, had flown before and chuckled at Namgyal’s reaction. They arrived in Ottawa on September 11 at 11 p.m., exhausted, but reinvigorated by the cheers and welcome signs offered by Miao friends and members of the resettlement. The main coordinator of the project, Cornelius von Baeyer, was there with his crown of white hair and wide grin, wrapping each new arrival with a white khata, a ceremonial Tibetan scarf. When the luggage dropped into the carousel, the new arrivals picked up their medium sized suitcases filled with all their belongings, and volunteers from the Tibetan Resettlement Project Ottawa drove them to an immigration reception home for their first week.

Namgyal and the others had their first orientation of Canada while staying at the reception home in downtown Ottawa organized by the Catholic Centre for Immigrants (CCI). Namgyal shared a room with Wangdak, and two strangers originally from Nigeria and Iraq. The reception home offered spartan accommodations. Their room had four single beds, a dresser with a mirror, and a table covered with bags of chips, Cheetos, and one litre bottles of pop. The walls were a clinical white, and there was a window that overlooked the street below and Gatineau in the distance. In the hallway, the doors were painted a sky blue and the walls were white and blue. A sign posted beside the one phone in the hall said, “please do not write on the walls.”

Each day, settlement staff from CCI helped the newcomers sort out government paperwork, such as applying for a social insurance card or Ontario health insurance. In between orientation sessions, Namgyal took his first chance to get a SIM card for his Indian mobile at the Rideau Centre. A couple times he wandered from the reception home to grab a hot chocolate at the Tim Hortons, located beside the Shepherds of Good Hope shelter in Lowertown. One day, Namgyal and Wangdak noticed the homeless people in the area. Wangdak wondered who they were and said they looked like them. At the time, they were both technically homeless, with their belongings bundled within their suitcases. Wangdak wore a grey sweatshirt and navy track pants with flip flops. Namgyal walked around in his jeans, plastic sandals and a black puffy winter jacket. Since arriving, he’s often seen wearing his puffy jacket, even when he’s inside a building. Canada was cold for him and it was only September.

After a week at the reception home, the Tibetans shifted into their host family’s home in Nepean, further away from downtown. Namgyal and Wangdak both lived with Pema Namgyal, a Tibetan from Ottawa who lives in the suburbs with his wife and their three children. They recently had a baby so to give them some space Namgyal and Wangdak would often stay at their Miao friends’ apartment near the St. Laurent Centre.

The pressure to get a job for the Tibetans coming to Canada was immediate in order to meet the resettlement project’s goal for each newcomer to be on their own, supporting themselves, in three months. In their first week at the reception home, Namgyal and his friend Wangdak, both looked worn out and overwhelmed by their new life. They were worried about going to their host family’s home in Nepean because they heard it was further from the city centre, and they thought it would be harder to find a job from there.

Namgyal and Wangdak at least had additional support from groups who’d arrived before them. These people met the three month target and had started setting aside a bit of money each pay cheque to help the new arrivals with their groceries for the first month. This was a pleasant surprise for von Baeyer who is constantly reaching out to the Ottawa community for donations.

The first 11 Tibetans from Miao arrived in Ottawa, one frigid night in November 2013 to temperatures of -16 degrees Celsius. Project Tibet Society selected this group to leave before the others because they were the most employable. Many of them had worked in Delhi before leaving India. “The Magnificent 11”, as the resettlement volunteers came to call them, took on the initial hardships of navigating the city and paving the way for the others who came later. Cornelius von Baeyer called it the “snowball effect.”

“One of them has a car and drives around and at every level they’re helping us with housing and integrating them into the community and doing activities with them,” he said.

Before Tibetans started arriving, Ottawa had a team of about a dozen resettlement volunteers trying to figure out how this whole thing was going to work. They decided they could take 90 people based on von Baeyer’s research that an individual refugee might cost at least $15,000 for the first year, meaning they would have to raise more than $1.3 million. The organizers agreed that they would fundraise and gather in-kind donations from the community to lower the estimated costs.

“We’d collect the money, they’d come, we’d collect some more money, so more people would come, but we wouldn’t get ahead of ourselves, and we haven’t – at all,” von Baeyer said. Both he and his wife, Edwinna, are retired and together they manage the majority of the resettlement in Ottawa. Edwinna collects in-kind donations from people, like gently used kitchen supplies, and furniture, such as beds and tables. Cornelius collects money through donations, assigns people to housing, finds mentors who will help integrate the Tibetans into Canadian society, and he makes sure the whole project works properly.

“We go with the flow and we invent things along the way as we have,” he said.

Without additional support from the government, the Tibetan Resettlement Project Ottawa can only accept people from India when they have enough money and housing resources to take care of them. They’ve managed to cover the costs for the 2015 arrivals, but now they’re trying to raise $35,000 to finance the final groups of newcomers coming in 2016. They’re also searching for more volunteers to help find housing, manage the coffers, and mentors to help with the one-on-one settlement efforts.

Namgyal and Wangdak had their own mentor to help them get settled, but sometimes they were on their own. Wangdak’s mentor went away on vacation for a month, and he didn’t get the support he needed from him while he was gone. In that case, because the resettlement is based on community effort, others stepped up to help Wangdak by taking him to appointments. Within two months, both Namgyal and Wangdak found work at the Salvation Army selling used clothing. They got the job through the assistance of one of the project’s volunteers in Ottawa.

“I went there with my resumé and I did an interview. After one month they called me for the job. I was shocked. I thought that they forgot,” Namgyal said. He works full time now, and doesn’t have much time for anything else. He said he’s too busy, “going to work, coming back from work, everyday work, work.”

Namgyal’s schedule keeps him from attending some of the Tibetan cultural events that have been offered by the expanding community in Ottawa. By November 2014, there were 33 new Tibetans in Ottawa. At one point, about twenty years ago, Jurme Wangda, who is now the president of the Ottawa Friends of Tibet, remembers being the only Tibetan in the city. Now, the white bearded sage said he’s finding strength in numbers and is working towards building a community centre that will offer Tibetan language, cultural and educational classes. There are enough Tibetans in Ottawa now that they’re able to celebrate Losar, the Tibetan New Year, as a public event. The newcomers have also made an effort to share their culture either at City Hall events, at local farmers’ markets or by hosting fundraisers.

At the 18th annual Ottawa Friends of Tibet fundraiser, in November 2014, there was a noticeable difference – this year some of the Tibetan newcomers brought their culture to life in front of a crowd of charitable diners. At the buffet table, waiters served up Indian food along with Tibetan momo, meat and vegetable dumplings made en masse by some of the people from Miao. Then, for the first time, Ottawa’s newly formed Tibetan dance troupe took the stage.

The dancers were full of energy and pride in their traditional dress called a chuba. The men wore a loose fitting white shirt and dark pants with a black apron and the women wore an ankle length dress with a multi-coloured apron across the front. The women and men each performed their own sequence and took turns dancing in front of each other. They smiled as their arms and feet moved gracefully to the upbeat folksy music from their homeland.

By the end of November, Namgyal and his friend Wangdak found an apartment with four other girls, who were also from Camp Three in Miao. All of them had arrived in Ottawa together back in September. The apartment is in the same building and a few floors down from another apartment full of Miao friends. Colourful prayer flags hang over the entranceway. At night, the apartment smells of onions frying and the sounds of female voices and laughter can be heard from the kitchen. In the corner of the living room is a Buddhist altar, where there is a large image of the Dalai Lama, his hands in prayer. On one side of the room, a giant Tibetan flag hangs on the wall, and an equally large Canadian flag is displayed on the wall across from it.

“Sometimes, I feel like I’m in my own place in Miao because we’re speaking our own language. After work, we talk about our village, our place,” Namgyal said. “I want to get well settled here in Canada. No more big dreams. No more big ambitions. I just want to be happy with my friends.”

NEXT PART

Credits

Story and visuals by SHANNON LOUGH

Carleton University 2015