Life in the big Canadian city

Dolma is not sure when she will be able to see her family again. In the first week of December she arrived in Toronto with a group of 11 people from Miao. Unlike those in Ottawa, she moved into a Tibetan owned reception home with the other new arrivals.

“We try to put them together in a house for three months basically to make them feel comfortable. By putting them together, they get support for themselves as well,” Palden Duga, one of the Toronto resettlement coordinators, said.

The reception home is a bungalow surrounded by a red wooden fence in the Etobicoke suburbs near a small shopping centre. The owner lives in the basement, and upstairs has been converted into a dormitory for the Tibetan Resettlement Project Toronto.

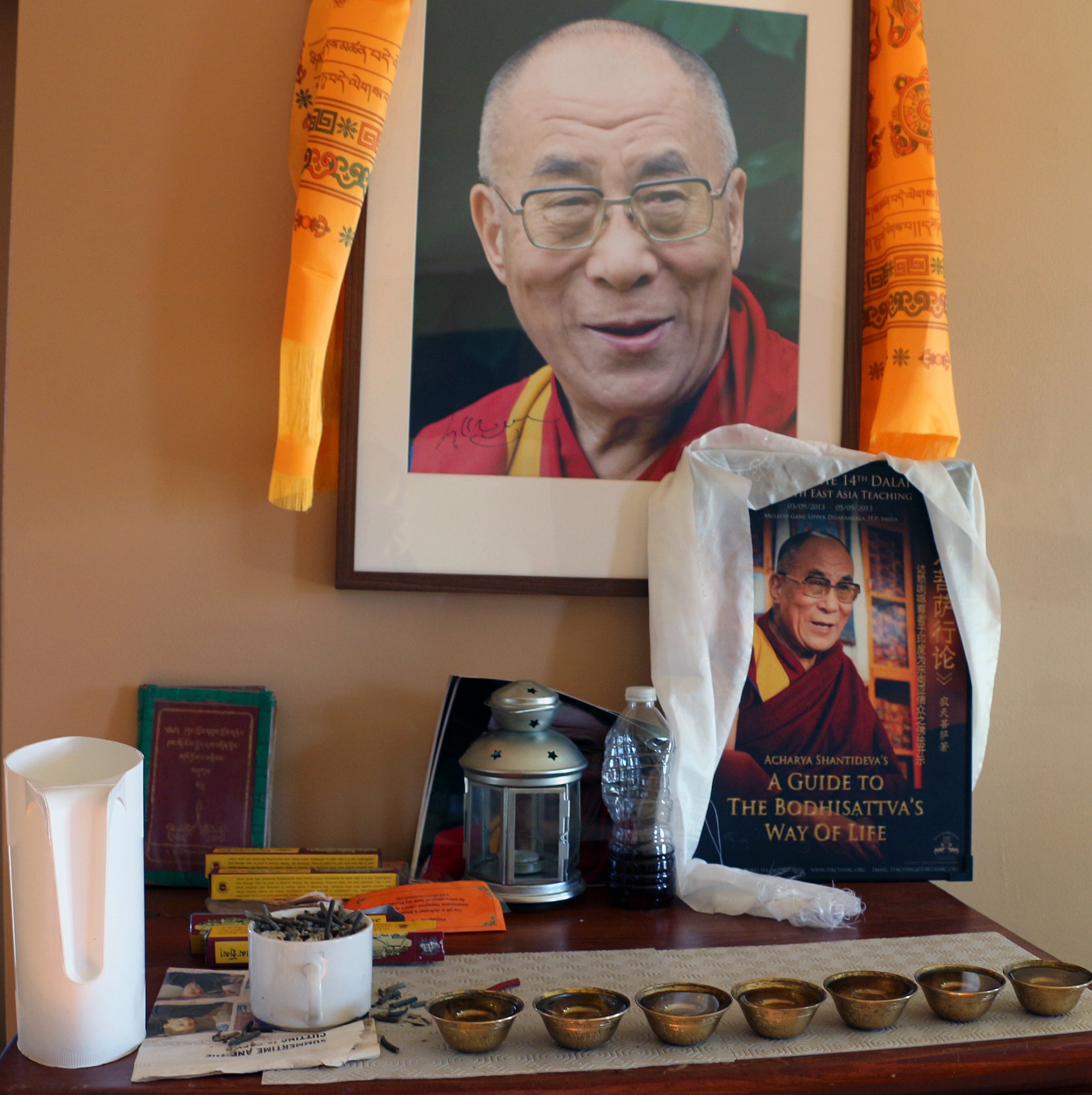

When Dolma was staying at the reception home in December, she shared the place with ten other people on the main floor. In the entranceway, a shoe filled rack stood against the wall and indoor slippers covered the doormat. The main floor smelled of meat cooking and possibly cabbage. The air was stuffy with so many bodies occupying the space. There were 11 single beds on the main floor, except the bathroom and kitchen were spared. There was a Buddhist altar, with seven metal cups filled with water, incense, a book on the guide to the Bodhisattva’s (an enlightened being) way of life, and a photo of the Dalai Lama with an orange khata scarf resting around the frame. People were constantly walking in and out, dropping off groceries, heading out to a new job, calling about a job on their phone, or leaving to visit friends in the city.

Calgary and Vancouver also have reception homes for newcomers but not everyone agrees with this approach. Mati Bernabei used to coordinate the resettlement project in Vancouver, but after a conflict of opinion with Project Tibet Society she resigned to be a sponsor for individual Tibetans coming over who need more care, such as the 20-year-old man she hosted who’d never lived away from his parents and didn’t know how to live on his own. There are other special cases too, like on the Sunshine Coast, where families that are moving there have no English or job skills. In British Columbia, the resettlement project has a mixed system. Some Tibetans go to the reception home and have to be on their own within three months to make room for the next group of arrivals, and then there are the Tibetans who need more assistance who can stay with a host family or an individual for up to a year.

“From the official Project Tibet Society stance, every single one of these (1,000) Tibetans who come in have to be up and running and working independently within a few months,” Bernabei said. She agrees that a reception home works for those who are ready to launch within three months but not everyone coming to Canada is.

“I’m worried about the transition home process creating gaps and chasms that people could easily fall through,” she said.

In Toronto, Dolma’s main concern was finding a job. In her first week she started searching for work and so was everyone else in the reception house. Her friend, Tsering Tashi, who arrived the same time as her, got a job in his second week at a catering business.

“It is normal,” Duga said about getting a job within a week of arriving. In Toronto, resettlement organizers help newcomers get their social insurance number and bank account to get them ready for the work. Once they hear about a job through one of their connections in the city they send the most qualified person for an interview, according to Duga.

“Dorjee Dolma is a little bit shy,” Duga said about his niece, “We are planning our best to get them an entry level job to get them speaking.”

Dolma reads in English, watches films in English, and speaks good enough English with a few cultural misunderstandings but when she’s around a stranger she shuts down and holds her tongue. Her insecurity didn’t stop her from applying for jobs even if it was done unconventionally. In her second week she went to a Tim Hortons with three other women, resumé in hand, asking for a job. She never heard back from them and didn’t know why.

Her resumé had too much white space. Her plainly typed words of actual experience only filled the top half of the page. Dolma’s cousin, who arrived the same time as she did, helped her put her qualifications on paper but it didn’t represent that she is multi-lingual in Pemako, Tibetan, Hindi and English and it didn’t promote the few work skills she had to offer.

All was not lost for Dolma. Her uncle Duga, and the Tibetan community in Toronto would keep her on her feet while she still tried to come to terms with her new world. She was amazed at how clean and quiet Canada’s biggest city was. A couple weeks after she arrived she explored the area around the CN Tower, but was too afraid to go to the top. Then she walked past a street vendor selling hot dogs without knowing what it was. She admits she doesn’t like Canadian food. In Miao all the food was grown seasonally in the gardens or purchased at the bazaar. She used to joke about it being organic; a term she heard people in developed countries used to charge more for naturally grown fruits and vegetables. The bananas and lychees might not look as clean and perfect as they do in Canadian grocery stores, but the flavour exploded in your mouth. In Canada, it was all a bit bland.

NEXT PART

Credits

Story and visuals by SHANNON LOUGH

Carleton University 2015