Part 1: Popularization

A survey by the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS) found that nearly 300,000 cosmetic operations took place in Colombia in 2016, the most recent year in which data is available. Colombia ranks No. 4 globally in terms of number of surgical operations per capita, and in 2015, Colombia ranked second after South Korea. Nearly five out of 1000 Colombians received a cosmetic operation in 2016 alone.

In addition, the 2015 survey estimated that between a quarter and a fifth of patients — about 71,000 annually —were medical tourists coming from predominantly the U.S., Spain and Canada.

Prices for cosmetic surgeries in Colombia are about 40 per cent cheaper than those in North America. The most popular procedures include liposuction and breast augmentation with over 44,000 of each of these operations carried out in 2016, as well as buttock augmentations and tummy tucks, each at over 22,000 procedures that year.

However, the actual number of people receiving cosmetic surgeries is likely to be much higher than indicated by ISAPS, as statistics are compiled from a database that includes information supplied only by certified plastic surgeons. Cosmetic operations that may have been carried out by non-certified plastic surgeons were not included.

Despite the high risks involved with plastic surgery in Colombia, the low prices and reputable work of many of the country’s plastic surgeons have lured countless thousands of medical tourists to the country. Some tourism outfitters in Colombia offer foreigners all-inclusive plastic surgery packages with multiple surgeries, luxury accommodation, airport transfers and post-operative care. Colombia’s coastal city of Cartagena is popular for its colourful colonial streets and tropical beaches, but foreigners seeking cosmetic surgery also flock to other large cities such as Cali, Bogota and Medellin.

Cristancho has had four liposuctions, an abdominoplasty, as well as butt and breast enhancements. “They have a lot of the best doctors here in Colombia,” said Cristancho. “It’s certainly a place I would always return to.”

“The potential for tragedy, fraud and grievous bodily harm is great,” Eckland has written. “The need for a well-trained, well-educated and objective/unbiased medical professional to formally evaluate these overseas medical sites is enormous.”

Prices for cosmetic enhancement are set at about 60 per cent of what a patient might pay in North America, and with Colombians living in a very different cultural context — including deep-set societal beauty standards promoting voluptuous figures with tiny waists — plastic surgery in Colombia is a big-money industry deeply integrated into the fashion, entertainment and tourism sectors of the economy.

History of Plastic Surgery

“The pursuit of a pleasing appearance is probably as old as Mankind and the references on how to embellish the eyelids found in the Ebers’ papyrus a thousand years before Christ demonstrate that the ancients definitely sought after a beautiful appearance,” wrote Paolo Santoni-Rugiu, author of A History of Plastic Surgery.

Santoni-Rugiu also noted that women in ancient Rome applied cosmetics with toxic silver, lead and arsenic to appear youthful. Women in Renaissance-era Italy used deadly nightshade eye drops to achieve a doe-eyed appearance and Victorian era corsets were tightened to the point of contorting the inner organs. Compromises between aesthetics and physical health have been made for centuries.

Body enhancements that we would today call plastic surgeries have been performed as early as 600 BC, with rudimentary rhinoplasties done in India. But most modern advances in plastic surgery arose during the First World War as thousands of soldiers disfigured by bullets and shrapnel required reconstructive surgery. Aesthetics as well as function became important for victims of head and facial disfiguration. Plastic surgery became a well-respected medical practice, although seeking operations purely for cosmetic reasons was viewed as superficial and self-indulgent by many in the medical community.

In the early 20th century, quack plastic surgeons made public demonstrations of cosmetic operations (entertainment analogous to modern TV shows such as Botched or Extreme Makeover), and while ethically questionable, this led to mainstream popularization. The post-Second World War women’s independence movement also gave affluent women the freedom to pursue commercialized procedures at their will. The following decades saw the proliferation of television and pop culture images that exaggerated beauty standards for women, a trend that drove consumer demand for body enhancements and which continues to this day.

According to an analysis of data from ISAPS, between 2010 and 2016 the number of people around the world annually receiving cosmetic surgery increased by 54 per cent. More than 10 million people worldwide underwent cosmetic operations in 2016, and the global cosmetic surgery industry is expected to reach total value of $27 billion by 2019, according to a report from Research and Markets.

Dr. Ernesto Barbosa, executive secretary for the SCCP, attributed the popularity of aesthetic surgery in Colombia to the warm climate and a desire to show skin — although the country’s infamous narco-trafficking industry is also known to have had a hand in the unusually robust development of the cosmetic enhancement industry.

“The first thing these men do is usually give money to their women so they can undergo cosmetic surgery operations to look better,” said Colombian professor of cultural psychology André Dydime-Dome.

According to Dydime-Dome, women in middle and lower classes in Colombia have often been regarded as sexual objects or trophies. They would use their physical appearance to gain the attention of wealthy men and use this as a means of climbing the socio-economic ladder and gaining material wealth. “It is something that occurs a lot in our country, and also occurs in contexts outside the culture of drug trafficking,” said Dydime-Dome. “I think that culture left something in our country.”

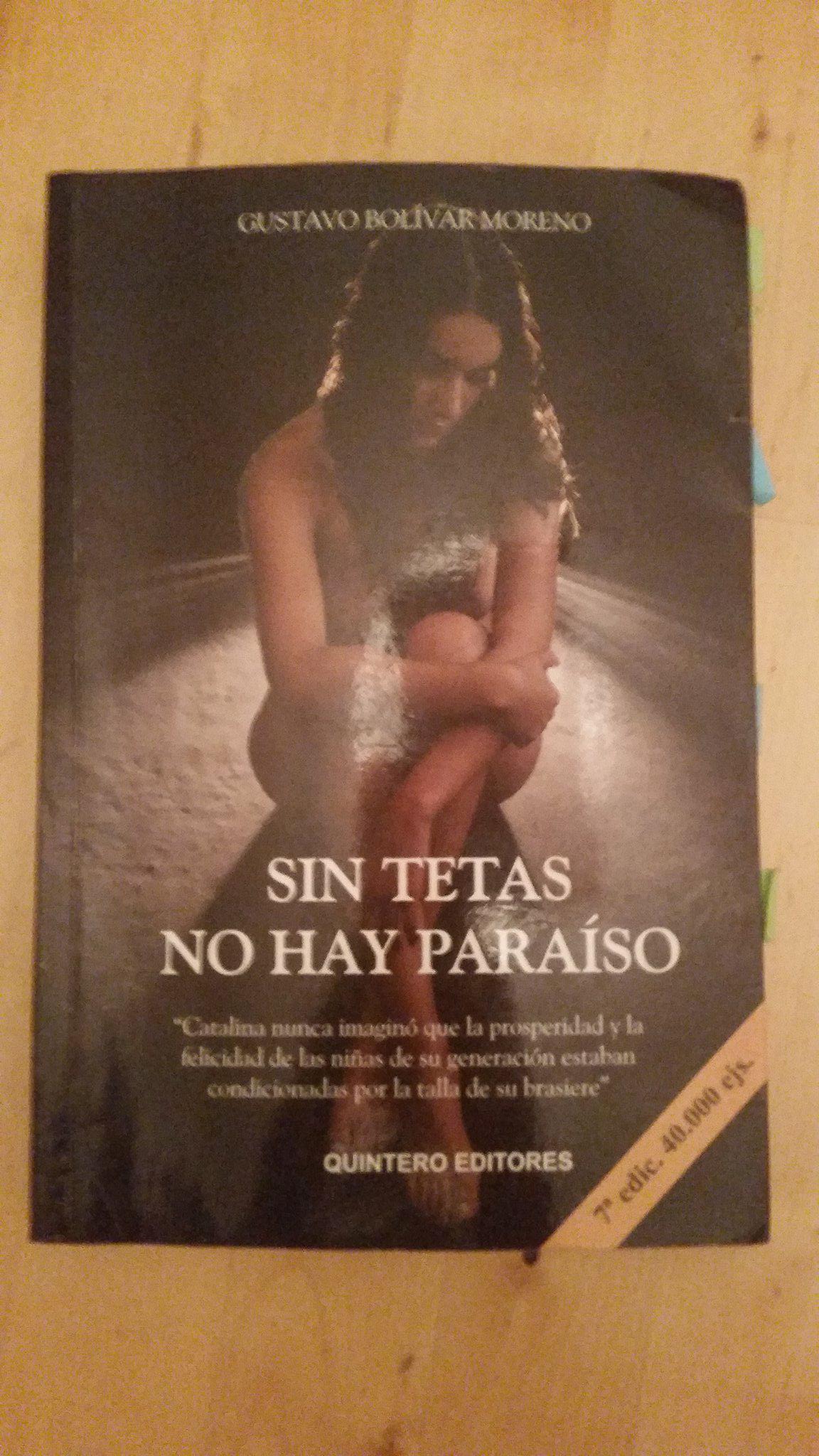

In the book, 14-year-old Catalina is envious of a classmate’s affluent lifestyle, made possible by her drug-dealing boyfriend. Catalina prostitutes herself in order to raise enough money for breast implants and gains the attention of wealthy narco-traffickers. However, Catalina discovers she was given re-used implants that caused a severe medical complication requiring their removal. Without her breasts and the support of her criminal husband, Catalina’s life quickly spirals out of control.

“Catalina never imagined that the happiness and prosperity of girls in her generation depended on the size of her brassiere,” reads the book’s tagline. Although Catalina’s story is a work of fiction, many Colombian women have faced, or continue to face, similar circumstances.

According to a report from the Inter-American Development Bank, Colombia also has one of the highest rates of teen eating disorders, estimated at nearly 20 per cent of that demographic cohort. “We could establish a connection between eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia and a person’s decision to undergo plastic surgery, as they share a root cause,” said Dydime-Dome.

Youth around 14 years of age are still developing a sense of self and are particularly vulnerable to outside social pressures, according to Dydime-Dome. “The dangerous thing is that a girl might get into the habit of continually seeking plastic surgery,” he noted. For a wealthy girl in Medellin, instead of asking for a car for her quincanera — the milestone 15th birthday — it’s not uncommon to ask for a new nose or bigger breasts.