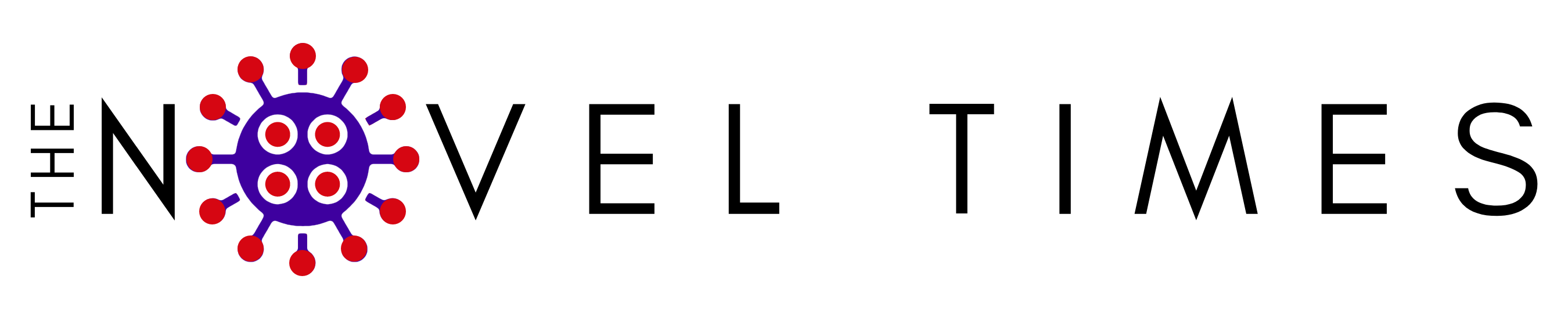

Left: Doug Lambie, a veteran of the Canadian Forces, poses with his uniform in 1943. Right: A grinning Doug Lambie enjoys his snack after flagging down the ice cream truck in the summer of 2018. (Photos provided by Malena Lambie)

OTTAWA – It was early on a Sunday morning when Rosemary Lambie’s phone rang. She knew what was coming. A nurse from Christie Gardens Apartments and Care in Toronto told her that her father had died around 12:45 a.m.

Lambie and her siblings could not be with him when he passed. Now they cannot be with each other as they grieve.

It’s said that funerals are for the living, not the dead. With restrictions on social gatherings, mourning has been put on hold for many families and communities.

Ontario forbids private get-togethers of more than 10 people indoors and 25 outdoors. In Toronto, where restrictions are tighter, residents are only allowed to meet outside at a distance, in a group of no more than 10 people.

While the gathering can be postponed, the grief cannot.

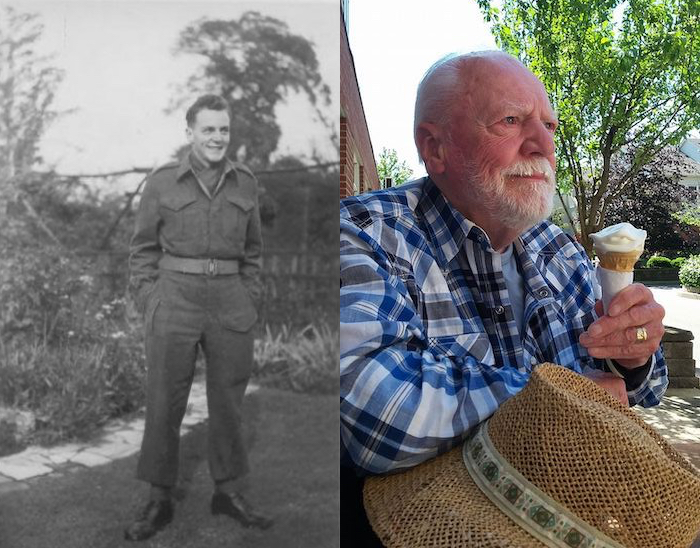

Douglas Lambie died of natural causes on Nov. 1, at the age of 96. His health started declining in September.

“I had been asking for weeks if I could go visit him,” said Lambie. “[The] home would not let me, because I was from out of province.”

Lambie lives in Montreal and works with the United Church of Canada. She oversees all of the churches in Quebec and Eastern Ontario down to the outskirts of Toronto.

Doug Lambie attends the wedding of his grandson Thomas in July of 2015, with family members Rosemary, Dave, Jay, Doug, Melissa and Malena. (Photo provided by Malena Lambie)

In September, she was in Oshawa for work, an hour’s drive from her dad. But she was told she would have to self-isolate in Toronto for two weeks before seeing him. Unable to take the extra time, Lambie returned to Montreal. Just over a month later, he died.

Jay, the youngest of Doug’s children, lives in Toronto and was the last of the family to see their father at the end of October.

“[Jay] phoned all of us individually. We were all able to say goodbye,” said Malena Lambie, Jay and Rosemary’s sister. She was grateful she could speak to her dad one last time.

While the gathering can be postponed, the grief cannot.

But Rosemary Lambie is still frustrated. “I’m carrying a lot of anger,” she said.

Doug and his wife Beatrice had four children, eight grandchildren, and 10 great-grandchildren.

The Lambie siblings keep fond memories of their father. Malena said he was never quick to anger except when she or any of his kids tried to snatch some Christmas turkey off the plate while he was still carving it.

Doug was wounded in battle during the Second World War and became a decorated veteran. He was also an avid singer. A proud Scot who often wore his clan tartan to spruce up his outfits, he ran a seamster’s shop in Montreal and made his wife’s wedding dress himself. Later, he helped her open a Scottish import shop in Ottawa.

The family gathered in mourning a month after Beatrice died in 2017. They had a barbecue, looked through dozens of family photographs and shared a lifetime’s worth of her stories. They did what many do when someone has passed – they leaned on each other physically, mentally and emotionally.

After Doug’s death, though, the Lambie clan cannot gather and draw strength from each other.

The rest of the family is spread out. Some live in Ontario, while others are in Quebec. This prevents them from gathering and mourning together.

The Lambies hope to place Doug’s remains in the cemetery alongside Beatrice’s on May 31. That day would have been their parents’ 69th wedding anniversary.

While the family anxiously awaits their next meeting, they are forced to deal with their grief in isolation.

Tara Cohen, a psychotherapist in Ottawa, said the inability to mourn collectively could lead to further issues.

She said that humans developed “rituals and traditions” for grieving that became essential to help people function after a loss.

“Having the opportunity to process and integrate the loss in a way that’s meaningful … it’s essential,” she said.

Cohen said the pandemic was “problematic” for those dealing with loss because it could affect their “emotional, spiritual, physical well-being.”

The Lambies are just one of many Canadian families facing the hurdle of COVID-19 restrictions while enduring a devastating loss.

Doug Lambie holds his seventh great-grandchild at a family party in 2017. (Photo provided by Malena Lambie)

Paul Adams is a spokesperson for the Canadian Grief Alliance. Formed in May to connect organizations, counsellors and community groups, the alliance is calling for a national grieving strategy.

As of now, grief is not covered under the mental health services that are included in the nationally subsidized health care system because it isn’t considered a mental illness. This leaves millions of people to fend for themselves.

“In normal circumstances, people who are well-situated use the support of their family and friends,” said Adams.

“Having the opportunity to process and integrate the loss in a way that’s meaningful … it’s essential.”

– Tara Cohen, psychotherapist

But the pandemic prevents families from being together and, ultimately, from grieving in an ordinary fashion, he said.

The alliance wants to see a more effective federal response than the one laid out in the Wellness Together Canada website. Adams said the website was useful for those dealing with depression,anxiety and other mental health issues, not for people dealing with loss.

He said the directives provided were actually counterproductive for someone who is grieving.

“We do not tell people who are grieving to go do things to take your mind off your brother, your sister or your husband or your wife or your best friend … that is not for people who are grieving a loss,” said Adams.

For Rosemary Lambie, some comfort has come through sharing stories about her dad with her children and grandchildren over video chat. It’s not the same as being together, but it’s something.