Maya* is pictured here at her emergency housing unit in Vanier. It’s a roof over her head, but it’s not a home.

M

aya* looked up. Her eyes widened, glistening at the sight of snowfall backdropped by the dark November sky. It was the first of the season. For Maya and her children, it was the first they’d ever seen.

In that moment, standing by the door of her bunk-bedded emergency housing unit in Vanier and watching the snowfall, she might have been able to forget that they had spent their first few weeks in the country wondering if their new home in Ottawa would be the streets.

Two months ago, they claimed asylum after fleeing Nigeria. They were among the asylum seekers who encountered a stretched system that puts affordable housing and even shelters out of reach.

“I was running for my life and I’m seeing life-threatening situations here again,” she said, referring to her family’s initial struggles to avoid homelessness upon arriving to Ottawa.

Maya spoke over the quiet voices of cartoon characters on the TV next to her. She sat cross-legged on her bed, leaning against the wall in a red Roots sweater, a maple leaf visible on the hoodie’s left side.

Maya is a single mother of five children, aged 12 to 22. They left Nigeria in early September fleeing the prospect of female circumcision. After two days in the United States they crossed the border south of Montreal with just $80. They made their way to Ottawa in search of an English-speaking city and a new home. The latter wasn’t as simple to find as they had hoped.

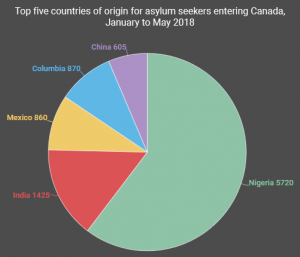

Like Maya, many asylum-seekers entering Canada come from Nigeria. Source: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

When they arrived in Ottawa, they went straight to an Ontario Works social services office. They expected shelter, but Maya said they were given just over $1,000 and told to get a hotel instead.

“How? I don’t know anywhere,” she said she told the social services office. “I don’t have a phone. I don’t know where to go.”

This encounter is typical for newcomers first arriving to the city, according to Stephen Porter, program manager at Matthew House, a small Nepean shelter for refugee claimants.

“There is very limited shelter space right now,” he said in a phone interview. People who are in shelters are staying in them longer due to the expensive housing market, he explained.

Porter also said that Ontario Works is on a limited budget, but claimants have the advantage of acquiring work permits within a few weeks of their arrival.

Still, for a family of six who had just stepped foot in Ottawa, Maya said she was shocked at the news.

The family didn’t have a choice. After a weekend at a motel they went back to the Ontario Works office, but there was still no availability.

Ontario Works suggested they sleep at a Greyhound Station.

“I was going back everyday for three weeks,” she said.

“We need to eat,” she stressed. “What is remaining is change because we are eating from the same money.”

Without an address, Maya couldn’t enroll her children in school, and the money they were given quickly ran out from eating at restaurants and spending $100 a night on accommodation.

Within 10 days of their arrival the family had maxed out the funding they were entitled to for the month – just over $1,500. Maya said that Ontario Works suggested they sleep at a Greyhound Station.

The funding that asylum claimants receive depends on factors like family size and the availability of shelters, according to Kim, an intake specialist at Ontario Works who did not want to use her last name for fear of job reprisal. For a single parent with three children under 18, the monthly limit would be around $1,625.

“It’s not a lot of money,” Kim said. “It’s kind of a crisis situation right now, people are coming to the city with not really a plan and nowhere to live and shelters are full, hotels are full.”

She said the best thing claimants can do is check shelter availability everyday.

“If they show up here with their family and there is no housing, it’s pretty sad to see people on the streets,” she said.

Over 50,000 asylum claims were processed in Canada in 2017, more than double the year before. As of October, the 2018 number sat at over 46,000, according to data by the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada.

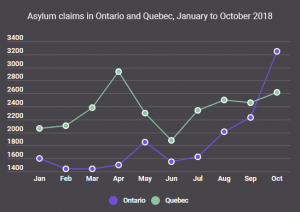

In October, Ontario pulled ahead of asylum claimants in Quebec, where many first enter Canada. Source: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

Attributing the housing problem to a refugee influx is a common misconception though, said Kailee Brennan, an outreach officer at The Refugee Hub, an organization that promotes human rights for refugees.

“There was a housing crisis here before there was ever an influx,” Brennan said. She explained that Ottawa has consistently not met its quota for building affordable housing for the city’s most vulnerable.

“We need to have spaces and housing options for refugees to integrate into our society after that initial stage,” she said, citing emergency shelters as merely a temporary solution.

Ottawa is struggling to keep up with demand. In 2014, the city began a 10-year plan to improve the affordable-housing system and has built over 350 units since then, according to the 2017 progress report. Length of stay in shelters and overall demand continues to increase though, especially for families in motels, whose numbers almost doubled from 2016 to 2017.

Maya and her family spent ten days in a motel until they could no longer afford it. Still, they never ended up spending a night on the streets, thanks to private organizations that are helping to fill the gap.

A woman they met at Ottawa Central Station directed them to a Catholic immigration service, they were then directed to a gospel church, where one of the nuns provided them food and shelter for ten days. After that, a space finally opened up in a city-funded emergency housing unit.

Maya said that she is more relaxed now. While the family waits for work permits and their claimant hearing, Maya volunteers at a food bank affiliated with the church. She often meets other refugees and assures them that there is “a light at the end of the tunnel.”

The gospel church still checks up on them everyday and provides them with clothing and food.

“I have life,” Maya said. “I’m functioning because people came around me to put me back on track.”

But a question remains, and it’s one Maya said her children ask her often: What if it didn’t work out that way?

“We call 911,” she tells them. “I can’t be on the streets in the cold. We’re not used to the cold. Call 911, let them arrest us. At least if they arrest us and take us to their custody, there’s a roof and a heater. We’ll be safe there.”

*The woman in this story has requested anonymity to protect her identity and not risk her claimant hearing.