Habib Zahori, an Afghan journalist and fixer who sought asylum in Canada around two years ago, has had trouble securing work in the industry he loves.

R

isking his life was part of the job for Habib Zahori, who confesses to missing the “adrenaline rush” of working as a fixer and journalist in his home country of Afghanistan.

“I miss everything about my past life,” laments Zahori, who worked with several media outlets including The Wall Street Journal, BBC and The Washington Post. In 2011, he was hired by The New York Times, where he worked until he decided to leave for the United States to pursue graduate studies in 2013. He moved to Canada three years later, to avoid living in a country led by President Donald Trump.

Zahori is among the refugees who worked as journalists in their former lives but were forced to reinvent themselves when they left their homelands. For some, the problem is lack of skills and recognizable credentials, for others it is sheer difference in style of journalism and type of stories covered.

Audio: Habib Zahori talks about being a journalist and fixer in Kabul.

According to George Abraham, founder and publisher of New Canadian Media, the situation is “bleak” and it is “impossible” for journalists from non-Western countries to build inroads into the Canadian media, considering that their experiences do not translate directly into a Canadian newsroom. “For a multicultural country we have a fairly monocultural media,” he said.

Zahori, who lives in Ottawa, finds there is no lack of work. He is working on two documentaries and a book on Afghanistan. However, he has not sought work as a journalist in Ottawa.

“I was a journalist in Afghanistan because I knew my country,” he said. Zahori stood witness to the changing Afghan governments, the civil war, the subsequent Taliban rule and the invasion of his country by American troops. Afghan politics and culture is a part of his life.

He believes that Canada, being an unfamiliar country, its history, politics and mentality alien to him, would pose difficulties for him as a journalist in Canada.“I don’t think I can do much as a journalist,” he said. Instead, he is working on a historical novel set in Afghanistan. Telling the stories of his homeland is his way of repaying his own people, he said.

Journalist from Mexico was also forced out of his home and his career

Luis Horacio Nájera dared to do what most would not. He went after drug cartels, corrupt politicians, and illegal arms dealers in embattled Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua — one of the most dangerous places for a journalist along the Mexico-U.S. border.

At least 74 journalists have been killed in Mexico over the past decade, according to the 2018 Congressional Research Service report on violence against journalists in Mexico. As the threats against Nájera and his family increased, he knew he had to get out. He has been living in exile in Canada since 2008. Nájera received the International Press Freedom Award in 2010 and the Human Rights Watch Hellman award in 2011.

Once in Canada, he quickly accepted any job that paid, including janitorial and painting work. A major hurdle was language. Though he tried to secure admission at UBC and Carleton University, he was rejected.

“My full-time experience as a journalist in Canada is only for six months,” said Luis, talking about the Toronto Star’s unsuccessful “touch tablet” project, which he worked on as content editor. According to Nájera, inadequate language proficiency, socio-political cultural differences and the local media’s lack of trust in the skills of a refugee journalist are huge hurdles.

“I am not really into journalism anymore,” said Nájera, who is currently a graduate student of Disaster Management at York University. When asked whether he missed being a journalist, he replied “Of course. You have no idea how much I miss journalism. People ask me, do I miss my country? I don’t miss my country, I miss my job.”

Video: Luis Horacio Nájera talks to Maria Assaf a Columbian-Canadian freelance reporter.

With shrinking newsrooms and rising competition, there is no room for training and nurturing someone who does not have the skills required in a Canadian newsroom, said Shawn McCarthy the president of Canadian Committee for World Press Freedom, who has 30 years of journalistic experience. “They need to be sure that you can do your job. It is just cut to the bone and everybody is going full speed,” he added.

Some journalists like Kameel Nasrawi have created a niche for themselves in the ethnic migrant media environment. Nasrawi, who had 30 years of experience as a journalist in Damascus, started The Migrant a publication that caters to the Arab and Syrian community. The paper was to fill the information and communication vacuum amongst the Arab community. But starting a media outlet in Canada is not easy. The lack of financial support or programs to support a media entrepreneur makes it very difficult, according to Nasrawi.

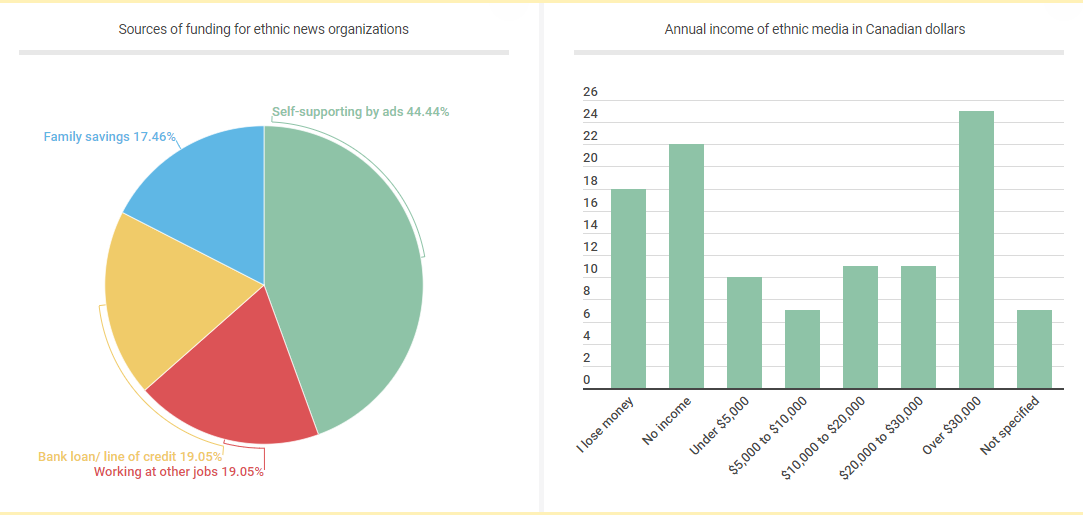

Many ethno-cultural news media organizations struggle to secure funding and generate income, often dipping into their own pockets or taking out loans to get by. Source: Canadian Heritage Publisher’s Survey.

The way forward seems to present a catch-22.“You need the experience to get the job, and the job to get the experience,” said James Milner, Carleton political science professor and research director for World Refugee Council. “We need to find creative ways for refugees to demonstrate their ability in a Canadian context and develop a track record,” he said.